The Ahadi (Promise) Quilts

Background

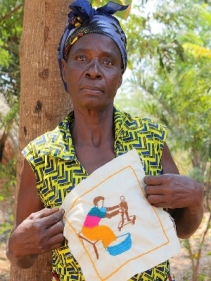

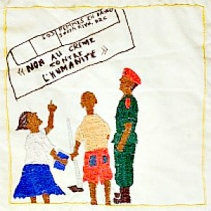

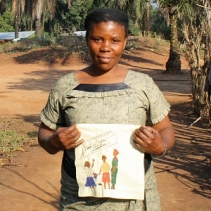

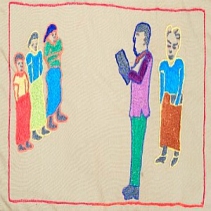

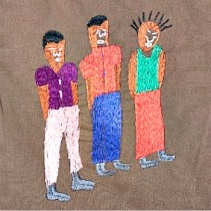

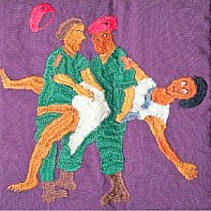

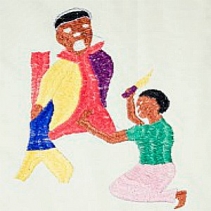

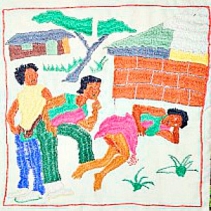

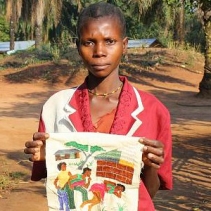

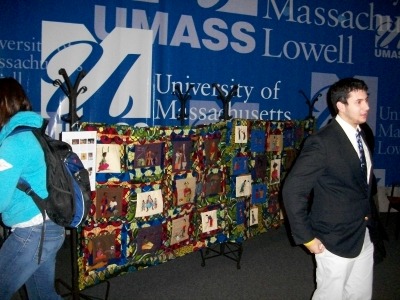

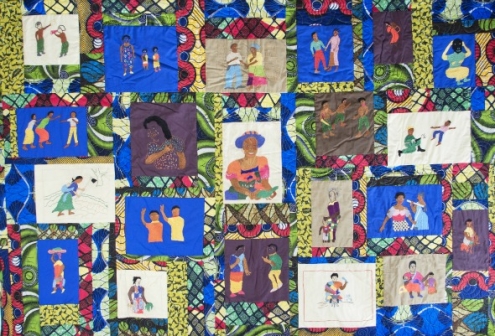

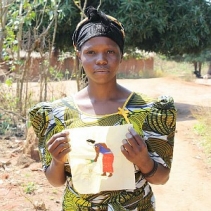

While his Mother Sews: Several squares depict violence against children, as well as mothers. The quilts profiled on this page are a ringing protest against rape by women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and by quilters in the United States. They complement the campaign to protect rape survivors that is run by AP’s Congolese partner, SOS Femmes en Danger (SOSFED) in South Kivu province. The Ahadi project was the third quilting project undertaken by AP after Bosnia and Guatemala. It began in the summer of 2010, when SOSFED and AP approached women who were recovering from sexual violence in SOSFED’s centers at Kikonde and Mboko. The women were invited to describe their experience through embroidery or weaving. SOSFED and AP explained the idea by sharing photos of the memorial quilts produced by women in Srebrenica and Guatemala. The response was enthusiastic. All the women then in centers – 120 in all – agreed to take part in the experiment. They named their project Ahadi, (“promise” in Swahili). SOSFED and AP had several goals in offering to support this project. First and foremost, we hoped it would be therapeutic. Second we hoped that the women would learn new skills and even earn some money, through sewing. Third, we wanted to build interest in the issues outside the Congo. Finally, we wanted to produce an advocacy tool that could be used internationally in lobbying for an end to the war. Our Congolese beneficiaries were consulted at every stage. This page tells the story of how the quilts were made and the women who made them – in the DRC and the United States. Embroidering SquaresOur first goal was to give the women a chance to express their feelings of disempowerment and anger. About a third of the survivors produced violent designs, but the rest preferred to remember better times and portrayed gentle scenes from village life. All of the women gave written permission for their names to be used and their photos taken. As the photos show, they also found it comforting to sew in the company of other women. This confirmed what we had seen in Bosnia and Guatemala – that sewing and knitting can help traumatized women to heal. This needs to be measured by specialists. OrganizationThe project was managed in the DRC by Amisi Mas from SOSFED, Ned Meerdink (AP’s field officer) and an AP Peace Fellow Amisi and the AP Fellow took charge of purchasing the material. They found that local thread was poor quality. After buying up all of the quality thread in Bujumbura, they went to Rwanda to purchase more thread and cloth. They also purchased several small wooden frames that held the cloth tightly while the women were sewing, and avoided wrinkles. Some of the women were impatient to get started and completed their squares without using a frame. As a result, many of their squares came our crooked and had to be remade. After further inspection, some were so powerful that we decided to use them anyway. This explains the duplicates. ProcessMost of the women had never even sewn before and we were unsure how to proceed. The AP Fellow and Amisi suggested six themes and let the women decide on an image. The project then hired a local artist, Nombi Baruani (photo) to help translate their ideas into designs. Nombi, who has a disability, makes a living from painting on walls or at markets and supports five children. The project paid him $1 for each square. He spent an average of 30 minutes with each survivor, and drew an outline in pencil on their pieces of cloth. The survivors then went to work with a needle and thread, under the supervision of SOSFED staff. While this was underway, the AP Fellow and Amisi took photos and wrote profiles of the quilters. Assembly Chasing down Thread: Amisi Mas from SOSFED went shopping for strong thread and cloth in Burundi and Rwanda. In September 2010, the AP Fellow and Ned returned to the US with 120 squares in their possession. A member of the Capitol City Quilting Guild in Lansing, Michigan offered the services of her guild to assemble half of the squares into three quilts. AP sought out the Faithful Circle Quilting Guild in Columbia, Maryland, and they generously agreed to assemble another three. Janet Munn served as coordinator for the Lansing group and worked by email with Peg McLelland and Sharon Rhoton in Maryland, to ensure that the quilting proceeded in parallel between the two guilds. The results speak for themselves, but the process of assembling the quilts was almost as noteworthy as the products. Just as the women in the Congo had found some closure through sewing, the US-based quilters agreed that working on the squares had opened their eyes to the war against women in the Congo. This comes out clearly in a video made by AP during the Columbia assembly. “You feel the anger and the despair….It’s very powerful to work with these pictures” said Susan Schreurs, a Faithful Circle quilter. Exhibitions in EuropeThe first Ahadi quilt was exhibited for the first time at the March 2011 meeting of the UN Human Rights Council, as part of a larger exhibition of quilts on the theme of women and war. Delegates to the Council passed the quilts on their way in to debate, and the exhibition had a powerful impact. It was organized by The Quilting Challenge, a partner of AP, and the Geneva office of the UN Population Fund (UNFPA). Alana Amitage, director of the office, spoke at the opening of the exhibition, alongside the American and Canadian ambassadors. The US Mission in Geneva posted a video on the exhibition. A few days later, on March 23, the second Ahadi quilt went public in Berlin on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations (IFA), which supports the SOSFED program in DRC. Marceline Kongolo, the director of SOSFED, and Iain Guest, AP’s Executive Director, used the quilt in their presentation. Exhibitions in the USThe six Ahadi quilts were shown for the first time together in late April, 2011, at the Intercultural Center at Georgetown University. The event also featured presentations by a former US Ambassador to the DRC, William Garvelink, and AP’s Iain Guest. The Georgetown event set the stage for a year of displays in the US, culminating in a major exhibition at the UN headquarters on March 8, 2012 – International Women’s Day. The event was hosted jointly by AP and the UN Population Fund, and was opened by four dignitaries – the Executive Director of the UNFPA, the deputy US Ambassador to the UN, the UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict and Marceline Kongolo, the 26 year-old head of SOSFED in the DRC. This was an enormous boost for SOSFED and for advocacy quilting. More than 80,000 people visited the exhibition over the next three months, and the visitors’ book showed how moved they were by the experience. Photos of the exhibition can be found on the AP Flickr page. Exhibition at Kean UniverisityBuoyed by the success of the Ahadi project, AP spent the rest of 2012 putting together a major exhibition at Kean University in New Jersey. During the summer, Peace Fellows helped to produce squares for ten more quilts and AP enlisted several more American quilting associations to help with their assembly. By the end of the year, AP and its partners had 24 quilts to exhibit. The president of Kean offered us use of the university’s spectacular human rights museum.  First showing at the UN: the first Ahadi quilt was shown at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, April 2011. Professor Henry Kaplowitz and the museum director Neil Tetkowski then worked around the clock with several dedicated students to make the show a rousing success. It was covered by the New York Times and The Quilting Life, and proved so popular that it was extended until September 2013. Two of the Ahadi quilts were included in the exhibition and never failed to stimulate discussion among Kean professors and students. Everyone asked how Congolese women, with no formal experience, could produce such breathtaking designs. The fifth Ahadi quilt went on display for one last time in 2013, at the Texsquare Museum in Washington. During these two years – 2012 and 2013 – the Ahadi quilts that were not in exhibitions were shown at private meetings with dignitaries or supporters of SOSFED. One was given to Diane Von Furstenberg, the fashion magnate who has supported SOSFED, as a special mark of gratitude (photo). Another quilt was shown to US Senate staff on the Capitol. AP also showed quilts to the DRC Ambassador in Washington. FundraisingOne enterprising young fundraiser in the US, eleven year-old Anna McGuire from the Pyle School in Maryland, met with Marceline Kongolo during Marceline’s visit to the US in March 2012. Anna was so taken by the Ahadi project that she put up a web page and raised $600 for two sewing machines. As she explained on her web page: “If we are able to provide two sewing machines to these courageous women they will be able to sew clothing and other items which they can sell in the market. If they have money they will be able to have power to make decisions for themselves and bring their families out of poverty.” Anna’s kindness has helped SOSFED to build sewing into its toolbox of services for women, and sustain the impact of the quilt project (below). SOSFED thanked Anna on video.  Students for the Congo: Students from the University of Massachusetts raised $2,000 for SOSFED after AP showed the Ahadi quilts in December 2011. Louis, from Quebec, seen in the photo here with Marceline at the 2012 UN exhibition, was another loyal supporter of SOSFED. Louis fundraised energetically for SOSFED until he died tragically from cancer in 2013. The artistry of the quilts, and their powerful message, has continued to inspire acts of generosity and kindness. Bianca Dipersio, a student at the University of Massachusetts in Lowell and her classmates put in long hours to organize a showing of the Ahadi quilts in December 2011. The event raised $1,000 and was matched by the university. Students at the University of Virginia, used the quilts at an event organized by ‘Take Back the Night,’ a student-led movement to stop rape on the campus. Quilting in the DRCWhile advocacy quilting has proved effective in the US and Europe, it has had less impact in the Congo itself. AP’s Iain Guest took one of the six quilts back to the Congo in 2012, and Iain and Amisi Mas, the SOSFED program manager, showed the quilt to new arrivals at the Fizi center. Dazed and reeling from their own ordeal, they found it hard to relate to the quilt. In addition, the artists had expressed concerns at their handiwork being shown locally – as opposed to abroad, where they were not known. SOSFED retains one of the six quilts for promotion, but uses it sparingly. However, SOSFED has been able to built on the quilting experiment and integrate sewing into its program. Amisi and Charlie Walker, a 2012 Peace Fellow, worked with a local tailor to produce several sample tote bags, carrying embroidered designs, which are now being tested in the US. Diane Von Furstenberg’s designer offered encouraging advice.  Uncertain Response: Amisi Mas from SOSFED showed one of the Ahadi quilts to new arrivals at the SOSFED Fizi center. They were too traumatized to fully appreciate the handiwork. Many 2010 beneficiaries were inspired by the quilts to take up sewing after they returned home. Hundreds more women who live near the SOSFED have received training at the Centers on the sewing machines provided by Anna. The cost of these trainings has been born by SOSFED’s own Board of directors, showing how an implanted idea can be sustained if a local partner is co-opted and motivated. Impressed and pleased, SOSFED’s German donor, Zivik, funded the purchase of sewing machines for the new center in Fizi Town. Even more encouraging was the news that several former SOSFED beneficiaries pooled their resources and bought their own sewing machine after they returned home. There are important lessons here for sustainability. Looking ahead, the Ahadi quilts will continue to make a proud contribution at any future quilt events in the US. Anyone interested in swing the quilts should contact AP. They can also download the text of a poster here and draw on a special collection of photos on the Ahadi project. Over the next year, AP and SOSFED will also increase efforts to generate revenue for the Congolese quilters. Greeting cards on all AP quilting projects, including Ahadi, are on sale here. For more information, click on the top right of this page. More details will be announced when they become available. The first challenge will be to create a product that sells, and generate economic demand. We welcome advice and help! |

First

First

|

|

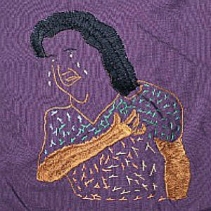

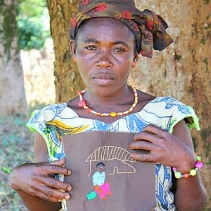

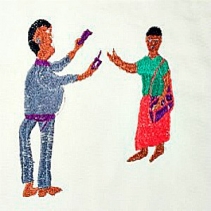

Elena Amisi Elena Amisi’s panel depicts a female advocate. She believes that people should “respect” women because if not for their mothers, they would not exist. |

|

|

|

Nyota Asende Nyota Asende (no photo available) says that, “rape victims without help never will find peace. Their lives feel like failures and they can’t move on.” |

|

|

|

Estha Sadoki Estha Sadoki was married at 17 after the death of her father left her family without means to survive. She wants to show how women must bear a double burden in society. |

|

|

|

Bakari Riziki Bakari Riziki shows a woman being chased from her house. This is what happens to mothers that are no longer important to their husbands in Congo. “One day he will wake and tell you to leave.” |

|

|

|

Furaha Tabaseelwa Furaha Tabaseelwa and her eight children were abandoned by her husband after her rape. She wanted to express the hardship of raising a family alone. |

. |

|

|

Neema Mlebinge Neema Mlebinge’s panel shows the difficulty of working in the field. Neema was forced to farm after her husband threatened to leave her for another wife. |

|

|

|

Rebeka Isisombe After being raped by four soldiers and the death of her husband, Rebeka Isisombe turned to SOS FED. “Our rights need to be respected, just like anyone else’s.” |

|

|

|

Noela Abety Noela Abety depicts the long-term effects of rape. Many women continue to deal with medical and psychological problems in an area where treatment is nearly impossible for them to obtain. |

|

|

|

Feza Denis Feza Denis aims to show the enduring difficulties faced by women who are abused by their husbands. “At home we are treated as less than men.” |

|

|

|

Fekele Lukubi Fekele Lukubi (no photo available) depicts a woman fruit seller because SOS FED is teaching her to support herself despite her life-long handicap. |

|

|

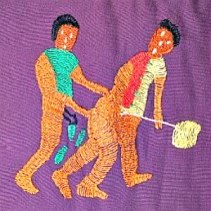

Seraphine Abedi Seraphine Abedi depicts a man beating his wife, “a regular thing in any Congolese house. Anytime a wife speaks in a way her husband doesn’t like, she is beat.” |

|

|

|

Ungwa Leontina Ungwa Leontina began quilting because “the world needs to be shown what life is like in Congo. Many of us are suffering in ways that they don’t suffer in the outside world.” |

|

|

|

Leah Byamutu Leah Byamutu wanted to show the difficulties of life in the Congo – even after recovery from sexual violence, the danger of other violence looms. |

|

|

|

Godelive Sadika Godelive Sadika is a refugee and widowed mother of ten. She wants to show the intense sadness of Congolese women caused by the ongoing warfare. |

|

|

|

Mariya Rajabu Mariya Rajabu is a twenty-year-old single mother who lacks any familial support. She hopes for peace so that people can once again walk far from their villages without worry and fear. |

|

|

|

Jacqueline Kabangomuli Jacqueline Kabangomuli came to SOS FED after being raped and kicked out of her home. Her quilt depicts the strength of these women in the face of adversity. |

|

|

|

Safi Mugozi Safi Mugozi (no photo available) shows a soldier shooting at a child to depict the situation in her village with the Interahamwe/FDLR militias and soldiers. |

|

|

|

Fahila Kabihona Fahila Kabihona (no photo available) wants her tile to “show others that our rights are born to us. Even those who are raped have the same rights as others, even men.” |

|

|

|

Furaha Kisindja Years after Furaha Kisindja’s children fled, she has no idea whether they are living or dead. |

|

|

|

Asende Wilondja Asende Wilondja became involved in the Ahadi project because she thinks that |

|

|

Second

|

|

|

Betina Masoka Betina Masoka’s panel depicts an image of a woman sewing, just one example of the Congolese women’s daily work they must do to survive. |

|

|

|

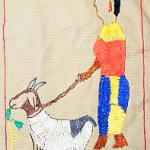

Regina Binwa For Regina Binwa, her image of a woman tending to livestock represents monetary independence that many women in the Congo lack. |

|

|

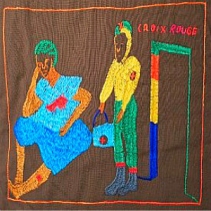

| Fatuma Byamtu Fatuma Byamtu’s (no photo available) panel shows a rape victim arriving at the SOS FED center, as she and many others have done |

|

|

|

Luize Mwajuma Luize Mwajuma’s panel depicts a rapist being judged and convicted, something she |

|

|

| Ngena Mchunga

Ngena Mchunga was raped repeatedly by two soldiers and became pregnant. She sells |

|

|

|

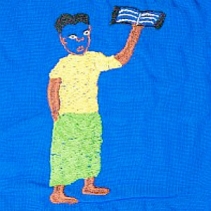

Nyota Assumani Nyota Assoumani was attracted to SOS FED because the program offered her the chance to learn new skills. “I wanted to improve myself, I wanted to learn,” she said. She believes that with education, women in the Congo will no longer be left behind.“One day we will have a female president if women are given the chance to learn,” she said. For Nyota’s full profile click here. |

|

|

|

Maria Mulala The day that Maria Mulala gave birth to her daughter, soldiers killed her baby and ransacked her house. Her husband died just a few days later. |

|

|

|

Erodiana Mpela Erodiana Mpela says, “Because of my rape I am known as a violated woman.” At the |

|

|

|

Bilombele Machozi Bilombele Machozi was raped while walking home from her fields far from town. |

|

|

|

Mahonyesho Nalukaba Mahonyesho Nalukaba was raped, lost her father and husband, and saw her house burned by soldiers in just one day. |

|

|

|

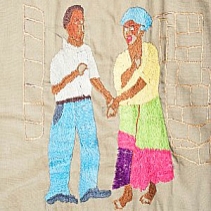

Judith Namegabe Judith Namegabe’s panel depicts a group of Congolese women demonstrating, armed by knowledge of their rights and the help of SOS FED. |

|

|

|

Mlasi Maulula Mlasi Maulula’s life and reputation were forever altered after being raped by seven soldiers just one week before her wedding. |

|

|

|

Namto Riziki Namto Riziki’s rich husband “feels shame” over her rape and thus resents and |

|

|

|

Maria Asende Maria Asende says, “Before the war, people had hope…. Now we have none. We work hard and keep nothing for ourselves or our families.” |

|

|

|

Moza Kakozi In her tile, Moza Kakozi wants to show that “it is children who suffer most from the war and violence in the Congo.” |

|

|

|

Ana Asende Ana Asende sees a brighter future for the DRC and believes that “as the war will come to an end, we will resume our lives and move on.” |

|

|

|

Feza Maonewo “War means repetition,” says Feza Maonewo. “There are short periods of peace, |

|

|

|

Martha Riziki Martha Riziki (no photo available) shows a women studying her rights because “civilians must know their rights.” |

|

|

|

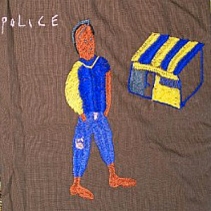

Elena Abwe Elena Abwe (no photo available) says that in the DRC, “The police don’t do anything for us, much less throw rapists in prison.” |

|

Third

Third

|

|

|

Neema Fatuma Neema Fatuma (no photo available) hopes that Fizi Territory “will find peace and return to the way it was before the war. In that era we could take care of ourselves and now we are often helpless.” |

|

|

|

Asende Selemani The war in the Congo left Asende Selemani’s (no photo available) husband disabled. A mother of eight, she saw her house burned to the ground while she was pregnant. |

|

|

|

Mlasi Sumaidi Mlasi Sumaidi (no photo available) depicted a woman learning about her rights from SOS FED staffers to show the world the way in which women benefit from SOS FED services. |

|

|

|

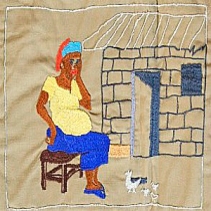

Jeanne Mwadjuma Jeanne Mwadjuma was raped, had a miscarriage, and now suffers from abdominal pain. Although Jeanne’s husband chose to stay with her and their two children, he blames her for giving him AIDS. |

|

|

|

Kesiya Inosa Kesiya Inosa says that “when war came, my family was gone and I was left alone and raped.” Kesiya dreams of working either for an NGO or as a secretary. |

|

|

|

Kashidi Selemani Kashidi Selemani’s (no photo available) eyes became permanently damaged after a blast hit her house. She wants to show the utter despair and helplessness she felt after the attack. |

|

|

|

Zainabu Shabani Zainabu Shabani depicted a woman working in the fields with a machete and a hoe to show the importance of the tools that provide her and her family sustenance. |

|

|

Arbetina Lúúbe Five of Arbetina Lúúbe’s six children died during the worst of the fighting. Rebels also shot her husband in the legs, leaving her as the sole breadwinner for her family. |

|

|

|

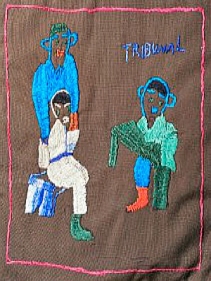

Marie Jan Kaseke Marie Jan Kaseke’s tile shows SOS FED workers teaching a group of women about their legal rights. “With the education I receive, I know I can be the agent of change in the Congo.” |

|

|

|

Mahombi Useni Mahombi Useni chose to depict a soldier begging for forgiveness. She is a powerful woman |

|

|

|

Alphonsine Losembe Alphonsine Losembe’s tile depicts her dream of a Congolese constitution on which everyone is equal and everyone’s voice is heard. |

|

|

|

Mlasi Machozi “When I was 13, I was raped,” says Mlasi Machozi. “I only made it through second level primary school. Everyone knew I had been raped and I was forced to leave.” |

|

|

|

Juma Lupango Juma Lupango was raped by four soldiers that burned her house to the ground. She said that she was not able to heal from the wounds of the war until she came to SOS FED. |

|

|

|

Zainabu Shabani Zainabu Shabani depicted a woman working in the fields with a machete and a hoe to show the importance of the tools that provide her and her family sustenance. |

|

|

Fourth

Fourth

|

|

|

Maria Madelena Maria Madelena despicts rape and pillaging by soldiers in her panel. She hopes it will help others to understand what happened to her and her neighbors. |

|

|

|

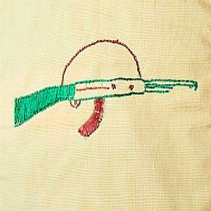

Maua Masudi Maua Masudi chose to depict an AK-47 because she’d like to show the world where war begins. “I want to show people what makes orphans in the Congo.” |

|

|

|

Laliya Byaombe Laliya Byaombe chose to depict a spear for her tile. Her village, Mboko, is a Mai-Mai strong-hold and during the early years of fighting Mai-Mai militia used spears in their battles. For Laliya, the spear represents the beginnings of the war and the horrors war has brought to her life and to the lives of the people of Fizi. |

|

|

|

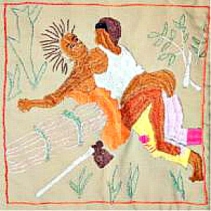

Esther Byussa Esther Byussa chose to depict a soldier chasing a woman for her tile because the quilt project made her think of the soldier that attacked her. During the war, soldiers forced their way into Esther’s house and killed her mother before raping her. “I want to show the world that war has come for women here,” she says. Esther says that her only hope is that peace comes to the Congo and that men and women can coexist in peace. |

|

|

|

Naeca Binwa Naeca used her tile to show militia burning houses. Even though the war left Naeca’s house untouched, it managed to destroy everything else in her life. Six soldiers raped her while she worked alone in her fields. Soldiers later killed her husband and pillaged her house. Naeca feels the stigma felt by most survivors of sexual violence in the DRC. “People treat me differently because of my rape; they feel that I am abnormal. It’s only because of SOSFED that I have the courage to say something to someone.” |

|

|

|

Fatume Lububi Fatume, 40, chose to depict a machete, which for her is both an instrument of peace and war.“Production and violence can come from this tool depending on the atmosphere it is being used in.” She says that she hopes the future is one in which the machete returns to its peaceful purpose. She enrolled in the SOS FED center at Mboko from August to November 2010. |

|

|

|

Chantal Ebúbú Chantal Ebúbú’s life was forever changed in 2003, when FDD soldiers raided her house, took everything of value, and raped her. Her husband, unwilling to stay with “a tainted woman,” left her to raise their four children alone. Chantal chose to depict the injuries she suffered after the war, and her subsequent medical treatment, for her quilt square. “I want testify about the terrible things that have happened in Fizi,” she says. |

|

|

|

Sifa Eca Sifa Eca depicted soldiers in her tile, because war has brought suffering to Fizi territory. Sifa sought the services of SOS FED because she needed a way to supplement her failing fields. With the help of the communal fields, Sifa can provide more food for her family. “In the future, I want peace,” she says,“peace will bring female equality and I will have a better way of providing for my children.” |

|

|

|

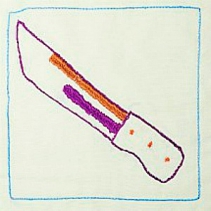

Jacqueline Yamungu Jacqueline Yamungu, 20, came to SOS FED after her rape, and is happy to have received some education after spending her entire young life out of school. She chose the image of a soldier attacking a woman with a knife because this is her remaining memory from the war.“At the time of the war, soldiers used knives because the bullets were more expensive and women were easy targets without even shooting them.” |

|

|

|

Mlasi Oredi Mlasi Oredi, 31, came to SOS FED because she wanted to find “a sharing place, where women can learn together to improve their lives and honor each other.” Her tile shows a refugee running with a bundle on her head because this is what she personally experienced in 1998. Through this image, Mlasi said “I want to show the suffering that women have lived through here, and the suffering that continues in our days.” |

|

|

|

Mtamba Mlasi Mtamba Mlasi, 21, has 5 children by 4 different fathers. She was raped at 14, and gave birth to her first child after that violation. Since then she has been rejected by her home community, and turned to prostitution among soldiers to feed herself and her children. When asked to come up with an image Mlasi chose a bow and arrow. She spent 2 years in Kigoma refugee camp in Kigoma, Tanzania. |

|

|

|

Salima Balongelwa Salima Balongelwa sought shelter at SOS FED after she was raped by three soldiers. As a mother of five, the issue of child soldiers is very important to her and her tile shows soldiers abducting three children. “I want to say that children have rights too — children also need to be protected,” she said. |

|

|

|

Ningejua Oredi After losing her entire family to war, Ningejua Oredi became extremely vulnerable to sexual violence. Her panel depicts a women and her child being thrown out her |

|

|

|

Anze Kasmon Anze Kasmon’s panel describes the way war can change people’s lives in an instant. It shows people fleeing for safety. |

|

|

|

Machozi Lukamba Machozi Lukamba, 30, was abandoned by her husband seven years ago, She was raped during the fighting, and became pregnant. Machozi chose the image of soldiers fighting with spears to show the world that “war in Fizi began at the hands of men holding spears. Then came the machetes. And then the AK-47s.” |

|

|

|

Binwa Nasango For Binwa Nasango, the spear is a frightening weapon because it symbolizes the beginning of violence and destruction. |

|

|

|

Fahila Salima Fahila, 26, was raped in 2009 while tending her fields near Kenya village in Fizi Territory. She chose to show children being abducted to serve in the armed forces. This is something she saw happening in Fizi Territory, and something that continues to this day. |

|

|

Fifth

Fifth

|

|

|

Mlasi Abwe Mlasi Abwe hopes that her images of a woman falling will show the world the need for peace in the Congo. |

|

|

|

Salima Sahidi Salima Sahidi uses her panels to graphically depict how women in the Congo are attacked every single day. |

|

|

|

Mawa Sango Mawa Sango is a victim of rape and mother of five. Her panel depicts the |

|

|

|

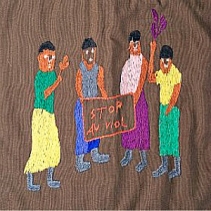

Sophia Mema Sophia Mema’s image depicts a woman who is being raped by a soldier. The woman screams, and raises her arms to let people know that she is being attacked, but nobody comes to the woman’s aid. For Sophia, this image signifies the ceaselessness and ubiquity of rape in Eastern Congo. “Raising awareness of this problem is important,” Sophia says, “because when people know what’s going on here, they can tell the government and the government can tell their soldiers to stop raping us.” |

|

|

|

Elise Asende Elise Asende (no photo available) was raped while farming, but continues to farm to feed her children. Her panel depicts this traumatic experience. |

|

|

|

Mardalene Zabibu Mardalene Zabibu depicted a soldier chasing a woman because of the frequent attacks on women in her home village of Mboko. |

|

|

|

Ecasa Mwenembele Ecasa Mwenembele’s panel is a warning to other Congolese women: collect water and firewood and tend to the fields in groups. |

|

|

|

Byaombe Endani Two Amani Leo soldiers raped Byaombe Endani (no photo available), as she tended her fields alone. Her husband later disappeared. |

|

|

|

Uziyah Mapatano Uziyah Mapatano (no photo available) portrayed a women being beaten by her husband to show “the life we Congolese and African women have to submit to.” |

|

|

|

Laheli Makololo After Laheli Makololo was raped and beaten, the soldiers shot her husband in the back. He is now disabled and dependent on her. |

|

|

|

Honorine Apoline Honorine Apoline’s tile depicts a man pushing a woman onto a chair. Honorine says that she chose this image because women are threatened by soldiers, “they burn houses, pillage, and attack women causing the problems that have become too common here; women don’t have any rights here,” she says. Honorine envisions a future in which she can live peacefully and provide her children with basic necessities. |

|

|

|

Julienne Ngalula Julienne Ngalula lost her husband and seven children in a massacre. She is forced to farm to support the surviving members of her family. |

|

|

|

Aci Masoka Aci Masoka came to the SOSFED center after she was raped and her life became filled with misery: “I became someone without hope.” |

|

|

|

Mwalihsha Mwenebato Mwalihsha Mwenebato (no photo available) depicts a crying woman. After being raped, she feels her rights have been forgotten and she has lost the support of the community. |

|

|

|

Sadi Mlebinge For Sadi Mlebinge the most devastating consequence of war is separation. “I have been separated from many people I loved after they died.” |

|

|

|

Andejala Maneno Andejala Maneno depicted a housekeeper about to be raped to show the dangers of doing manual labor. |

|

|

|

Bahati Johari Bahati Johari’s name means “luck”. She was raped at age 12 fetching water for her family and has since |

|

|

Sixth

Sixth

|

|

|

Emmerence Lehani Emmerence Lehani (no photo available) depicts herself, exhausted after a hard day’s work in the fields. Manual labor is a common hardship for women in Congo. |

|

|

|

Unga Mwashamba “War comes, it leaves,and it comes again,” says Unga Mwashamba, who depicts the daily hardships of war in the Congo. “This repetitive theme never ends.” |

|

|

|

Martha Alembe Martha Alembe wanted to convey the difficult life of women who continue to perform their arduous chores during times of conflict and instability. |

|

|

|

Tantine Misa Tantine Misa (no photo available) is a married mother of four, whose panel depicts women in the market. Women are often the primary economic providers for their children and relatives. |

|

|

|

Salima Bakari Salima Bakari (no photo available), became a single mother when her husband left her during the war. Her panel depicts the pressures of single motherhood. |

|

|

|

Josephine Ungwa Josephine Ungwa (no photo available) chose to depict a woman who has been thrown out by her husband and is forced to beg in the street of her vilage. |

|

|

|

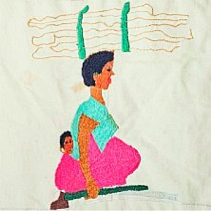

Fatuma Kashindi Fatuma Kashindi’s husband left her when she became pregnant after being raped. “Wherever I go, I carry my children on my back. Sometimes, the world is on my back.” |

|

|

|

Riziki Amisi Riziki Amisi’s (no photo available) husband has been ill for the past seven years, so she struggles to earn enough money to pay for her children’s meals and school fees. |

|

|

|

Namenge Machozi Namenge Machozi’s panel, depicting a woman cultivating, communicates the hardship Congolese women face when men force them work. |

|

|

|

Sinaona Akili “We are forced to live mediocre lives due to the endless violence,” says Sinaona Akili, who lost her parents in the war. “The war and the rapes and murders leave us with nothing.” |

|

|

|

Tabu Asende Tabu Asende says, “Before war we didn’t know violence. Now that the rebels have raped and pillaged us, killed our fathers and children, and burned our houses, we know violence well.” |

|

|

|

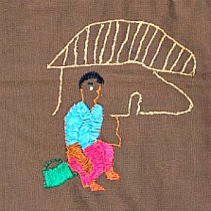

Albetine Nyange Albetine Nyange has been able to earn supplemental income to support her family by sweeping for neighbors, a chore depicted by the woman in her panel. |

|

|