Latest Posts

-

High School Students Bear the Brunt of Enforcing a State Ban on Food Waste in Rhode Island

Leave a Comment

Doomsday scenario: Rhode Island’s single landfill receives 722 tons of food waste a day and could run out of space by 2040

Many school administrators in the state of Rhode Island are ignoring a new law to divert food waste from landfills, leaving students to carry the burden of persuading over-worked school staff and reluctant fellow students, according to a new survey launched by two high school activists.

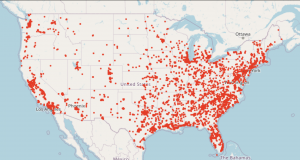

The law is one of only six in the US and is viewed as a major response to the growing threat of climate change at the state level. It took effect on January 1 last year and requires all schools in Rhode Island that produce more than thirty tons of organic waste a year, or lie within 15 miles of a composting facility, to compost or recycle the waste and donate unused food to food banks.

In spite of its importance, the law suffers from a lack of enforcement provisions and funds according to Emma Pautz and Bella Quiroa, two rising seniors at high schools in Rhode Island who also advise The Advocacy Project. As a result, implementation of the law is left to schools that are struggling with many other competing priorities and threatened by budget cuts.

Ms Pautz and Ms Quiroa have launched a survey and petition, the Youth Composting Campaign Initiative, to drum up support for the law. They presented preliminary findings recently at a composting conference sponsored by Rhode Island College in Providence, the state capital.

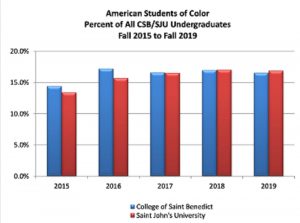

Of the 74 teachers to have responded to the survey so far, 65% had not heard of the mandate and only 9% reported that they had a “strong” composting program that involves students. Ms Pautz described this as deeply discouraging. “Obviously, it is not good enough” she said in her presentation.

*

Rhode Island is blessed with a spectacular coastline and is heavily dependent on tourism, but both are at serious risk from garbage and climate change, according to speakers at the recent conference.

The state has one landfill and at the current rate it will fill up by 2040, forcing Rhode Island to export waste to other states at a sharply higher cost than the current $58.50 a ton. Alarmed legislators are considering a bill to impose a surcharge of $2 a ton on all garbage collected to encourage new thinking.

Food waste should be the first target according to Josh Daly, associate director at the Rhode Island Food Policy Council. The state sends 722 tons of food waste a day into the landfill where it is converted into methane gas, one of the deadliest greenhouse gases, he said.

The federal government’s Environmental Protection Agency is also urging states to focus on the linkage between food waste and climate change and has offered Rhode Island $50 million to implement a climate action program. Of this, around $2 million is earmarked for food waste.

Ms Pautz and Ms Quiroa are also outraged that so much food is going to waste in a state where under-nutrition is high among low-income families and minorities. Almost 14% of all Rhode Island households receive supplemental food from the government.

*

The looming threat from climate change is producing a generation of student leaders who are, in the words of Emma Pautz, “terrified” by what lies ahead.

Ms Pautz herself was inspired by Greta Thunberg, the Swedish climate activist, at the age of 12. Soon after arriving at the Barrington High School, where she studies, Ms Pautz got two composting bins set up in the cafeteria and persuaded other students to join her in monitoring the bins. The nearby Barrington Farm School collects the waste for free on an electric bicycle, and by last summer Ms Pautz’s team was diverting over 12 gallons a week.

Bitten by the green bug, Ms Pautz spends weekends clearing nature trails and draws praise for her commitment. “Emma has a passion for environmental projects and doesn’t let anything stop her,” said Amy Nicodemus, Ms Pautz’s school advisor. “I wish we had more young people with her drive!”

Bella Quiroa, the campaign co-leader, came to composting through an internship at Clean Ocean Access, a non-profit in Newport, that enabled her to introduce composting to younger students at five other local schools. Last Halloween she collected over 80 discarded pumpkins from local farms and held a carving competition, Carving for Compost, for students and families.

“The pumpkin guts and bits were composted as people carved, and the excess pumpkins were donated to a local farm for their cows to eat,” said Ms Quiroa. “The idea was to raise money in a fun way and protest the fact that so many pumpkins go to waste and end up in landfills.”

Ms Quiroa has also given composting presentations at her church in Spanish and English, using 5-gallon buckets donated by local businesses. “It is so rewarding to work with communities!”

*

For all their achievements, the experience of Ms Pautz and Ms Quiroa also exposes the limits to student activism.

Several participants at the recent conference noted that younger students at elementary and middle schools are open to composting because they accept direction and like new ideas.

But high school students are more resistant to authority and can be resentful of initiatives by other students, said Ms Pautz. She recalled one student who tossed several uneaten apples into the trash bin in front of her, as an act of spite. “Monitoring food scraps is not seen as cool,” she said. “Most kids would rather sit and talk to their friends.”

This has not deterred Ms Pautz. One of her fellow composters, Sabine Cladis, said that they regularly stand up on chairs and “yell” at other students. “We can be pretty aggressive!”

But Ms Pautz also complained that their campaign had been undermined by her school board, which suddenly decided to take over composting from students last summer. “When we turned up for the new school year, the bins were gone. When I asked what had happened, they said ‘Oops – we forgot.’”

This forced the students to start from scratch, and they are currently collecting less than a quarter of the 12 gallons a week they binned last summer. Ms Pautz added that the Board’s inaction had sent a message that composting was not seen as a priority by the school authorities, weakening her standing in the eyes of other students.

At the same time, Ms Pautz conceded that school administrators have many other worries on their plate. Her own school is facing a serious funding deficit and is also struggling to implement a state ban on smoking.

Composting in schools presents other challenges. Several respondents to the student survey noted that food service in their schools is outsourced to Chartwells, a catering company, and called on the company to do more to support composting in school kitchens and cafeterias. Chartwells did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

Finally, it is sinking in that Ms Pautz and Ms Quiroa will graduate next summer, and that their efforts will probably come to an abrupt halt if they cannot coopt other students to take over when they leave. “Sustainability is a big worry,” said Emma.

*

If students play a key role in implementing the state ban, teachers are uniquely placed to help.

Tyson Edmonds, a teacher at the The Prout School in the town of Wakefield, offers a course on environmental justice that has inspired his students to compost up to five gallons of food waste a day in the school cafeteria, for use on the school garden. Several students attended the conference last week and were quick to sign the survey and petition by Ms Pautz and Ms Quiroa. Some have started composting at home.

Katie Bowers, a teacher at the Birchwood Middle School in Providence and compost enthusiast, said that it requires constant effort to keep students interested and come up with new ideas. These have included “zero waste days” and encouraging students to plant a mixture of squash, beans and corn which she calls the “Three Sisters.”

But this is definitely producing a change in behavior, said Ms Bowers. More and more students are putting food scraps to one side on their lunch trays, making it easier to toss the waste into the bins.

Ms Bowers also said that teachers can act as cheerleaders with school custodians, who manage school garbage, and with catering staff. After some initial skepticism, the kitchen staff at Birchwood are now solidly behind composting and help by putting scraps and unused food to one side when they clean out fridges and salad bars.

Ultimately, however, “change must come from the top” in any school, said Ms Bowers. While a new district school superintendent can breathe life into a food waste plan, the reverse can also happen. The principal at Barrington High is new and the superintendent of the school district will retire this year. Ms Pautz’s advocacy with school authorities appears to be back to square one.

*

For all the zeal shown by state legislators in passing the ban, there appears to be little stomach for tougher enforcement that would put more pressure on school boards and principals.

Nor does the state seem ready to offer more funding, with the exception of climate-related money, although experts feel money should not be a significant impediment.

The waste from the Barrington High School is picked up for free. While other schools pay for haulage, the cost rarely exceeds $50 a week for smaller schools according to Justin Sandler at Black Earth Composting, which works with around 15 schools in Rhode Island and charges $24 to haul a 64-gallon bin. “If they really want it, schools find the funding,” he said.

One source of funding is 11th Hour Racing, a foundation that has supported two nonprofits working with schools, the Rhode Island Recycling Project and Clean Ocean Access.

Jim Corwin, a co-director at the Recycling Project, said that his group has helped 13 schools to launch composting in the Providence area. Between them they have diverted 100 tons of waste and recovered 13 tons of unused food in the last three years. The Club has also made the case for composting with principals and school boards, including at the Birchwood School.

Elsewhere in the state, however, food waste diversion suffered a major reverse earlier this year when Clean Ocean Access unexpectedly closed down without any public explanation. The group had supported composting at 11 schools on Aquidneck Island, which includes the district of Newport, and sponsored Bella Quiroa’s outreach to elementary students. Advocates say that that the group’s demise has further undercut the state’s faltering efforts to implement the ban.

*

If Bella Quiroa and Emma Pautz are unnerved by the pressures, they did not show it at the recent conference. Judging from their survey, most schools are unaware that the state ban even exists, and the two students plan to change this by making as much noise as possible. Their petition has attracted over 700 signatures in less than a month and they plan to use this in approaching the media, schools, boards and legislators.

“We need to get some urgency into this,” said Ms Pautz. “It’s as simple as that.”

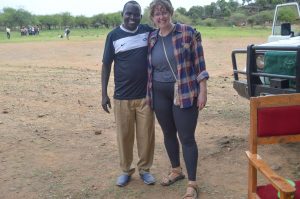

Managing climate change: Bella Quiroa, left, and Emma Pautz, right, join Sarah Lavallee and Maggie Lauder in cleaning up Newport beaches, which have been battered by storms

*

-

The Greening of Kibera

Leave a Comment(Second of two posts)

As we move through Kibera it becomes clear that the Shield of Faith composters love green vegetables almost as much as they love their worms. If their first goal is to manage garbage, improving nutrition comes a close second.

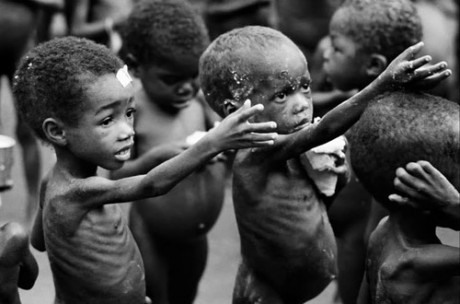

Most vegetables sold in Kibera are grown in sewage. This has contributed to under-nutrition and stunting among children. Added to which, food is so expensive that it can account for a third of a family’s weekly bills.

Stella Makena, the group coordinator, has long dreamed of producing organic food here. This seems far-fetched given that very few families in the settlements have a back yard, let alone access to cultivable land. Yet twelve of the 20 composters erected kitchen gardens and grew their own food in 2023.

The gardens themselves are miracles of innovation, fashioned from recycled wood and old plastic containers into which are added soil, seeds and Lishe-Grow leachate produced by the worms. Some composters have also begun to grow vegetables in vertical plastic towers, which can be taken apart and are fed with water from the top. The towers are perfect for a confined space.

Most of the gardeners grow collard greens, known locally as sukuma wiki, which is sturdy and nutritious. Kale, cabbage, strawberries, lettuce, cucumbers, maize, tomatoes, onions and pumpkins have also graced their gardens. Some varieties can last up to 4 months before they are exhausted and need to be replaced with new seedlings or cuttings. The discarded plants are composted.

Stella is the group’s green guru and she visits her gardeners regularly to offer advice and encouragement. Water and soil pose the biggest challenges. One enthusiastic gardener, Roseanne, keeps chickens which provide her garden with manure. But when we visited, the soil in her plastic towers was drying out too quickly and causing her vegetables to wither. Stella recommended adding worm castings and compost.

Gardens are treated like members of the family. Beldine has covered her plants with a blanket of recycled netting to protect them from the sun and heavy rains. Stella’s verdict: “Beldine – you’re a star!”

So much effort, but does it produce any food worth speaking of? I put the question to Stella while nose high with some drooping sukuma wiki in another garden. Not to worry, she said, the plants would perk up after being watered. Vena, the owner of the garden, told us that she harvests vegetables three times a week and makes each batch last for several meals. In addition to the nutritional benefits, Vena saves money on food bills.

All of which was music to Stella’s ears. The idea of growing organic food in the middle of such an unhealthy environment appeals to her deeply.

*

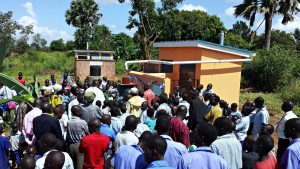

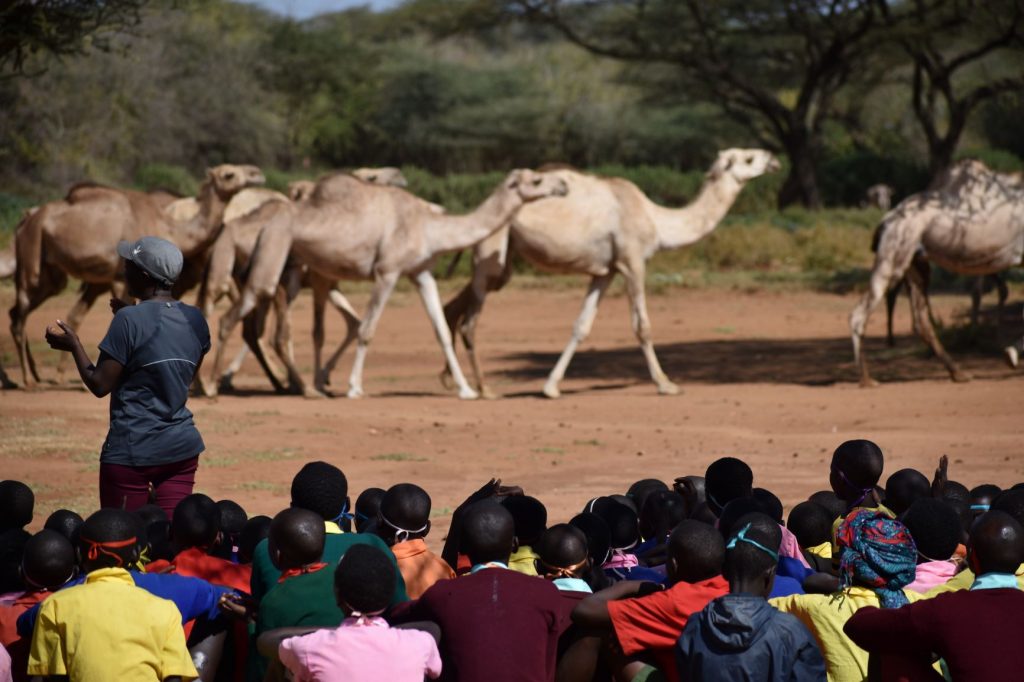

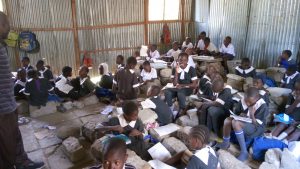

The Kibera composters understand that on their own they will have a negligible impact on a settlement of over 200,000 souls that generates around 230 tons of garbage a day. As a result, they hope to take their model out into the community and become, in Stella’s words, “catalysts for change.”

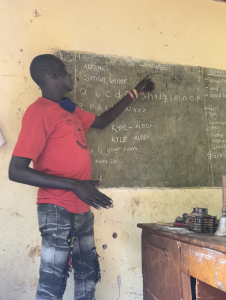

One point of entry could be public schools, which offer a daily cooked meal to students and in the process generate prodigious amounts of organic waste. Once composting catches on in one school, predicts Stella, others will follow.

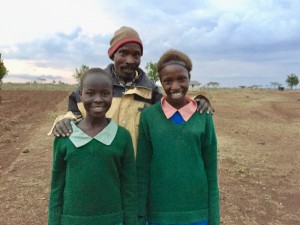

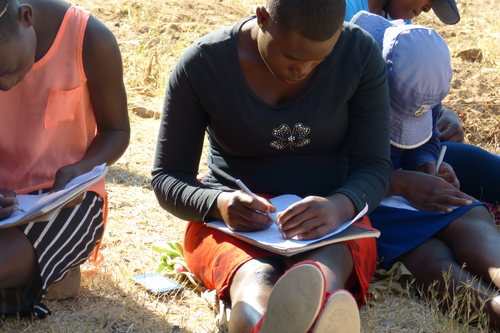

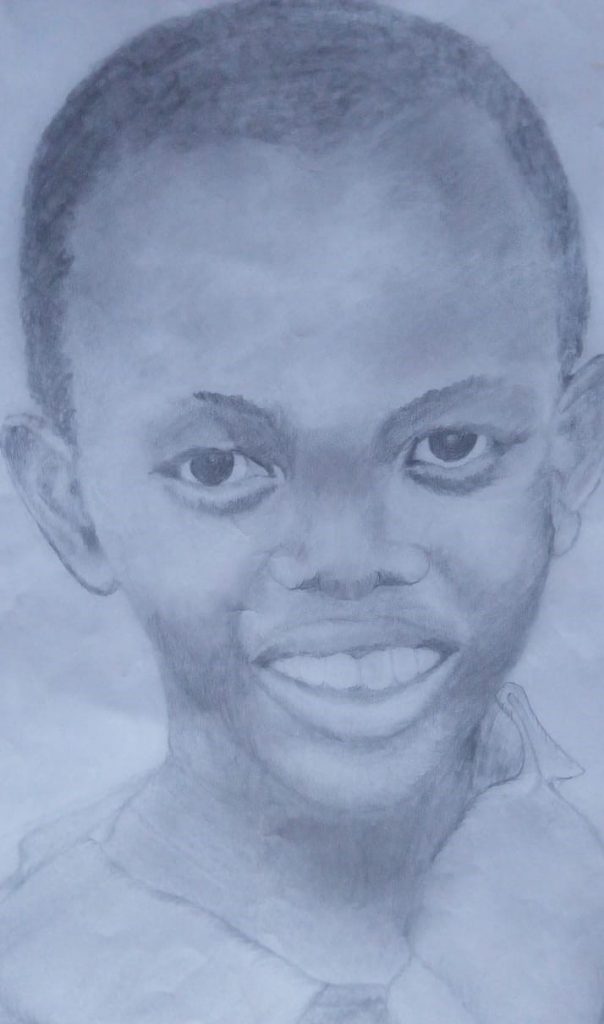

Stella took a step in this direction last year when she and Vena erected a kitchen garden at Project Elimu, a well-known after school program that offers ballet and art to over 200 children from Kibera schools at weekends and many more during the holidays.

The children are happy to get into the dirt and Michael Wamaya, the visionary founder of Elimu, was delighted to add gardening to the curriculum.

“Kibera is very rough on children,” he told me. “But when we show them how tomatoes grow, they want to water the plants. This brings out a kindness in them and affects the way they deal with other children.” One of Michael’s top students, Felix, has agreed to serve as a Shield of Faith “green ambassador.”

*

Under Stella’s 2024 plan, ten composters will collect organic waste from their neighbors and create “composting hubs.” This, she hopes, will build interest and start creating demand for composting in the community at large.

The creative chaos of settlement life will help. Outside the Elimu center, the streets are alive with vendors selling fruit, vegetables and cooked snacks like kangumu (crunchy cakes) or mandazi (a local donut). Some variety of food is found at every corner and most of it generates organic waste that could be composted.

Some hubs are already under way. Eunice collects waste from her neighbors to feed her large garden, which is an island of green in a sea of gray grime. Several other Shield of Faith members use her garden to plant and harvest their own vegetables.

At first sight, hubs are beyond the reach of composters like Catherine and her son Biden (named after the US president), whose rooftop garden was demolished when their landlord added a new level to the building. Ruth is another composter who lives several floors up and has no back yard.

But Ruth is determined to grow her own food and she has persuaded the local authority to lease her a tiny strip of waste-land a considerable distance from her building. The land was littered with rubbish when we visited but the prospect of going green was already putting a smile on Ruth’s face.

Sure enough, after several weeks of hard work, the ubiquitous sukuma wiki was sprouting in Ruth’s garden and a new composting hub had been born. Stella’s before and after photos (below) say it all.

Iain Guest is Director of The Advocacy Project. Read the first article in this series

*

-

Composting Empowers the Worm Ladies of Kibera

Leave a Comment(First of two posts)

The Advocacy Project is observing International Women’s Day (March 8) by acknowledging twenty women who composted 3.9 tons of organic waste in Kibera, Nairobi, and several adjacent settlements last year. Twelve of the composters also grew organic vegetables in kitchen gardens that they assembled from recycled materials.

This is no small achievement in communities that are known throughout Africa for pollution, overcrowding and under-nutrition. It is even more noteworthy given that most of the women are single mothers. Ten also have children with albinism, a skin condition that often causes affected families to shrink from public view.

But not this group. The composters have formed an association, Shield of Faith, and this year they plan to launch a series of composting “hubs” in an effort to change the attitudes and behavior of their neighbors. I visited them last Fall in the company of Stella Makena, their tireless coordinator, to understand their obsession with composting.

*

The settlements of Nairobi are called informal for a reason. Almost all of the services are provided by NGOs and an army of local entrepreneurs, many of them totally unscrupulous.

In one example, electricity is tapped (illegally) from power lines that run above the houses and sold to residents at exorbitant rates. There is no such thing as maintenance and shortly after our visit Margaret, one of the composters, learned that her eight-year old granddaughter had touched a live wire while playing outside and died instantly. Margaret had to find 14,000 Kenyan shillings to pay for the funeral – equivalent to two months wages – while coping with her grief.

Albinism adds to the anxiety. Some Shield of Faith mothers have dealt with albinism by sending their children to boarding school to protect them against bullying, superstition and violence in the settlements. (Margaret’s son was almost kidnapped and killed.) Others cannot bear to live without their children and keep them as close as possible.

We visited one of the most active composters, Ruth, who has two children with albinism and one without. The four live together in a single room high up in a gloomy tenement building in the settlement of Huruma.

There are no lights in the stairwell and Ruth hauls heavy buckets of water up through the gloom several times a day, using her phone’s flashlight to avoid a tumble. Up on the fourth floor the family shares an open toilet and shower with others that live on the same corridor. Water is so precious that Ruth saves what she can from washing clothes and dishes to flush waste down the toilet. Garbage is taken downstairs and dumped.

Once inside the family’s room, you are immediately struck by the lack of personal space. Until recently Ruth slept on the floor, which was bone-chillingly cold during winter. She has since purchased a large bed that can accommodate her and her son on one mattress and her two daughters on an upper level. But the bed takes up a lot more space and is now squeezed awkwardly between Ruth’s sewing machine and cooking area.

Such trade-offs are normal in the settlements. “I’m struggling but I’m trying!” said Ruth cheerfully.

*

I asked Ruth why she goes to the effort of composting in such a confined space. Does it not create more or a burden? She answered by introducing us to Red Wriggler worms that live in blue composting bins (“wormy bins”) in the corner and munch their way through her food scraps. Ruth plunged her hand into the muck and pulled out one of the creatures for our inspection. “I live with these worms,” she says happily. “We have to share this tiny space!”

Their alliance works because the worms allow Ruth to manage her garbage. The more she composts the less she has to haul down and out into the streets. The worms also keep Ruth’s waste free of odor – most Shield of Faith composters clean out their bins every six months. And of course Ruth’s worms turn the food scraps into mulch that can be sold or added to gardens.

Composting produces other benefits. The project has purchased scales for each composter and Ruth weighs the leftovers after every meal before adding them to her bins. Collecting data regularly in such conditions requires discipline but produces a sense of accomplishment and a modest income that has paid for Ruth’s new bed.

Under Stella’s system (“pay to weigh”) each composter receives 800 Kenyan shillings a month to weigh and record the amount she composts. Stella then enters the data into an online “output tracker” that is accessible to our team in the US, volunteers, donors and (if need be) auditors.

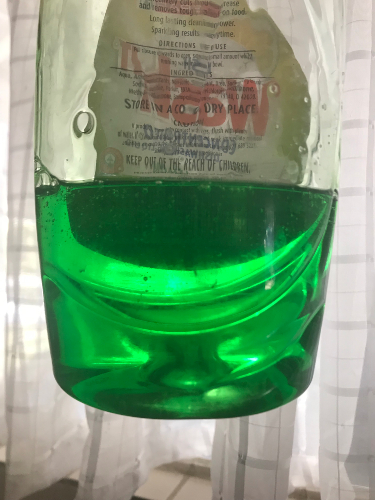

The worms also secrete a highly concentrated liquid, or leachate, that the composters drain from the bottom bin. They have named the leachate Lishe-Grow (“Grow Nutrition” in Swahili) and last year they bottled 522 liters, exceeding all expectations. They sold 42 liters and hope to sell more in 2024.

Several composters add Lishe-Grow to their kitchen gardens. Stella also plans to use it on a plot of land outside Nairobi that will be converted into a center for cultivation and training later this year.

*

All of this is hugely impressive, but the bottom line for Ruth is that she is transforming waste – including even worm poop – into something of value.

This rounded off my own education. I visited Ruth thinking that the rigmarole of composting – collecting, weighing, binning, reporting, managing worms, and draining leachate – could only add to the pressure on these women.

I left realizing that nothing could be further from the truth. Composting allows Ruth to manage her home and gives her agency in a cruel environment that robs her of many basic rights and services.

Iain Guest is Director of The Advocacy Project. Tomorrow – The Greening of Kibera

*

-

A Foe of Forced Marriage Ties the Knot in Zimbabwe

Leave a CommentWhen I first met Trish Makanhiwa in 2019 she was reeling from the loss of her mother and terrified that she might be forced to find a rich husband to keep her brother in school and pay the family’s bills.

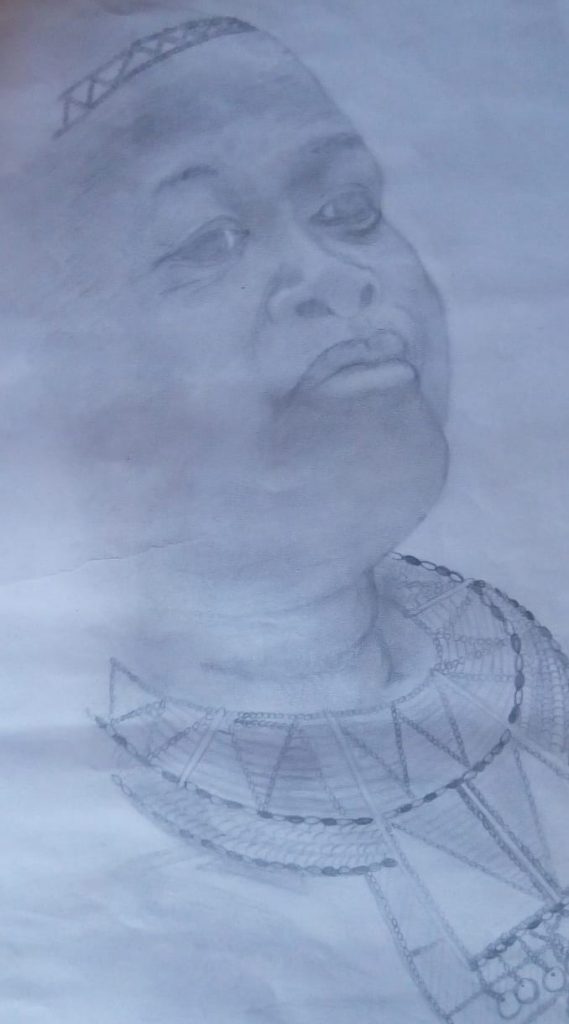

This past year was a lot different. Trish, 23, supervised the production of more than 70,000 bottles of soap that earned over $45,000 for vulnerable girls in inner-city Harare as well as providing her with a good salary. Capping the year off in style, Trish married her sweetheart, Alvin (photo above).

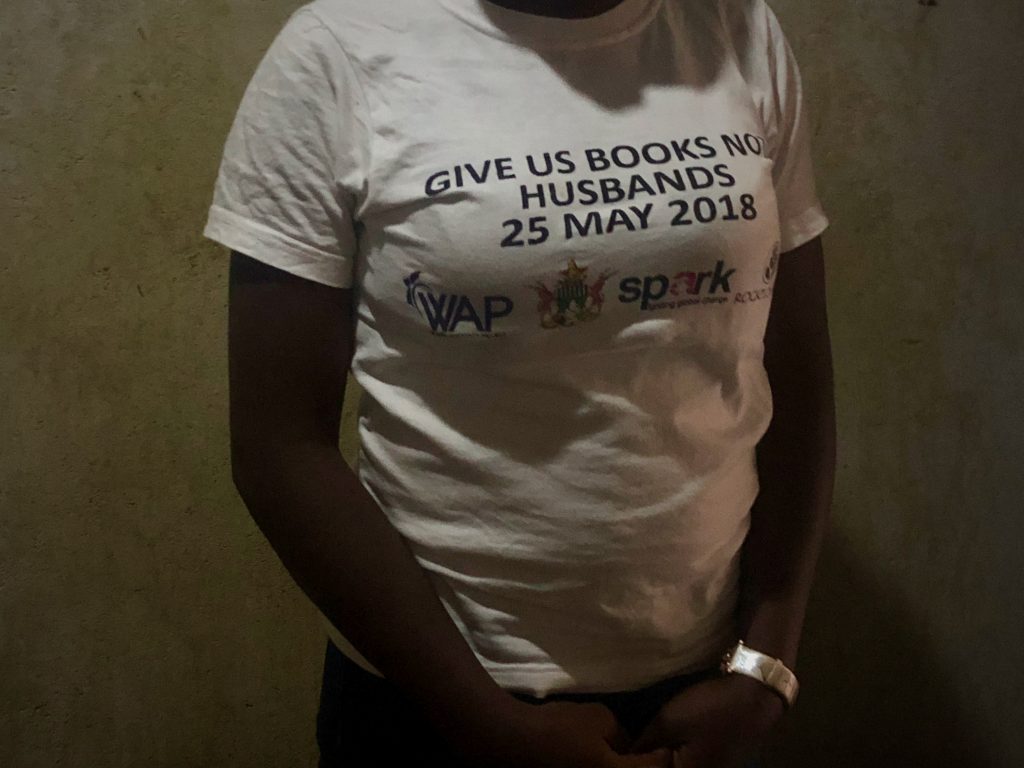

That she has survived and thrived says much about Trish’s strength of character and the resourcefulness of her employer, Women Advocacy Project (WAP), an advocate for women and girls that formed in 2012 to combat child marriage.

Over the past five years WAP has explored many different ways to protect girls from being pressured into marriage. Selling soap tops the list because it reduces the threat from poverty, but WAP has also trained girls to express their fears through embroidery and volunteer in their communities during the darkest days of the pandemic. The organization has also encouraged girls to think internationally by reaching out to students from American high schools.

Every activity has been aimed at giving girls the confidence to choose their own path. Trish has been at the center of it all and Constance Mugari, the founder of WAP, gives her credit for WAP’s most singular achievement. Over 300 girls have worked on the soap program since 2019 and not one married below the legal age while she was with WAP.

Trish’s own marriage, on her own terms, also vindicates Constance’s conviction that the challenge is not marriage itself so much as coercion. “Trish inspires us all,” she told me. A deep friendship now exists between the two women.

*

Early marriage in Zimbabwe has long been a target for advocates and in 2016 Zimbabwe’s constitutional court responded by raising the minimum age to 18. Almost 35% of all girls in Zimbabwe are thought to marry before their 18th birthday compared to 2% of boys. This can be extraordinarily dangerous for young girls during pregnancy and puts an abrupt end to their hopes of education.

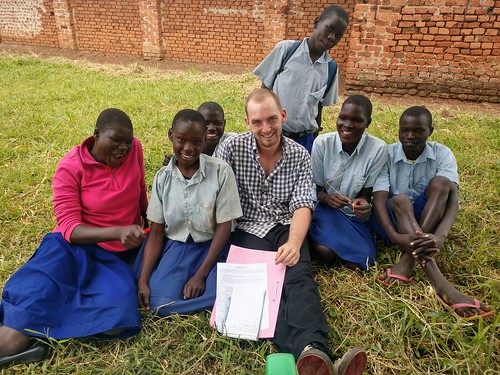

The Advocacy Project joined WAP’s campaign in 2018 by recruiting Alex Kotowski, a student at Columbia University and former researcher at Human Rights Watch, to help identify the causes of early marriage. Alex found that one of the worst offenders was a local religious sect known as the White Garment Church, which encourages followers to marry off daughters as young as 12 on the pretext of curbing their sexual activity.

McLane Harrington from the Fletcher School, our 2019 Peace Fellow at WAP, deepened our understanding by examining traditional Shona practices like Kuripa Ngozi which requires families to give a daughter in marriage to pay off a debt or make amends for a crime.

As part of her fellowship, McLane also helped eleven girls who were active in WAP’s program to express their fears through embroidery. One young artist, Beauty Tembo, showed a girl who has been driven from home by her parents after becoming pregnant and is contemplating suicide. Such cases were known to the artists. There is real terror behind their images.

But if traditional practice was part of the problem the main driver behind child and early marriage was also hiding in plain sight, namely poverty.

Tanatswa Sachiti’s story shows a 16 year-old girl who was left to care for six siblings after her parents died and had no choice but to seek an older husband. Tanatswa herself is unmarried. I visited her home in 2019 and was told that her family earned an average of $5 a day. Under this sort of pressure, it is hardly surprising that many families sell their daughters off to wealthier older men.

*

Constance Mugari’s first goal has been to build a culture of peer support for girls. She began by establishing two clubs and selected a tough-minded girl to head each club and serve as an “ambassador” against early marriage. Evelyn Sachiti took the lead in the neighborhood of Chitungwiza, and Trish was elected to head the club in Epworth.

This approach relied heavily on peer support. The clubs would meet every weekend to discuss marriage and if Trish or Evelyn found that a girl felt threatened, Constance would intervene with her parents. I visited the two ambassadors at home in 2019, and found Evelyn to be bubbly and talkative. Trish was reserved and shy. It was very clear that both were deeply respected by other girls in their groups.

Having identified poverty as the primary enemy, Constance and her husband Dickson Mnyaci looked for a practical response. They decided on soap, which is easy to make and guaranteed a market. We raised $4,712 through a GlolbalGiving appeal and asked McLane Harrington, our 2019 Peace Fellow to help launch a start-up. WAP hired a soap trainer, came up with a catchy name (Clean Girl) and started selling in local stores known as “tuck shops.”

By the end of 2019 WAP had sold over 3,000 bottles and when I visited Harare in November, soap-making was in full swing. It was joyous and messy. The girls mixed and bottled their soap in a vacant house before heading out in teams to the tuck shops. Plenty of soap was spilled as bewildered parents looked on.

I also realized during that visit that nothing boosts confidence so much as persuading someone to buy something you have made. This is central to WAP’s business model, which relies on the girls to find customers, and even the most timid soap-sellers clearly felt the buzz when they made a sale. I filmed Trish bargaining with two traders in 2019 and was pleased when her heroics convinced a US donor to invest in the program.

*

COVID-19 tested the resolve of the WAP girls by putting a halt to their soap-making, deepening poverty and increasing the pressure to marry. But it also brought out their creative side.

The government of Zimbabwe took fright at the prospect of the virus invading overcrowded neighborhoods and imposed one of the most draconian lock-downs in Africa. Women were arrested for trying to collect water. Small traders were violently dispersed. Thieves came out at night.

Faced by these new threats, the WAP girls returned to story-telling and produced powerful embroidered blocks about lock-down. We assembled the blocks into a quilt and profiled the artists in a 200-page catalogue which I shared with Trish and the other girls last summer, much to their delight.

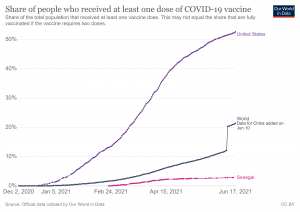

Soap-making stopped when the pandemic struck but the WAP girls were restless and Constance spotted an opportunity. She began sewing face-masks while her husband Dickson made soap at home. They also launched an appeal through The Advocacy Project on GlobalGiving which paid for cooking oil. The oil, masks and soap were then assembled into Care packages and distributed to vulnerable households under the direction of Trish and Evelyn. They also mobilized over 200 neighbors to get vaccinated.

During the pandemic the two ambassadors built a partnership with American students at the Wakefield High School in Arlington Virginia, who were also struggling with the pandemic. The Wakefield students had decided to stitch their own stories of lock-down and the two groups met regularly on Zoom to compare designs and help each other manage their COVID blues. Inspired by the partnership, the Arlington students made their own Clean Girl soap and raised $622 to help with school fees in Zimbabwe.

*

Of all WAP’s goals, earning money is most important because it removes the main pressure on girls. The production of Clean Girl soap today bears little resemblance to the inspired experiment of the early years.

In 2023 WAP produced an impressive 70,162 bottles (compared to 3,000 bottles in 2019) and earned $65,932. Of this, $49,126 was shared between the participating girls. The rest was re-invested in the program.

This was the result of a production overhaul that began during the pandemic. COVID-19 forced WAP to reduce the number of soap-makers to eight and move production to Constance’s house. Several donors then chipped in with carefully targeted interventions. Together Women Rise helped to pay for soap ingredients. Rockflower funded the construction of a small factory adjacent to Constance’s home, where the soap could be mixed and bottled. Action for World Solidarity in Berlin and FEPA in Switzerland paid for solar panels and a bore-hole that would ensure a regular supply of water.

The program also benefited from the presence of Dawa Sherpa, our 2022 Peace Fellow, who was born in Nepal and relishes field work. Dawa helped WAP secure a vehicle from the Swiss Embassy, install the solar panels, and improve efficiency by using Google Drive as a virtual office.

When I visited WAP this past summer, the process was working like clockwork. Trish, Rosemary and Lynes mixed the soap until it was thick and gooey, let it settle in large tubs, and poured it into 750 ml green bottles. The bottles were then shrink-wrapped in packages of six and readied for distribution to the network of young soap-sellers. The three producers receive a salary and transport allowance on top of what they earn from sales – a serious income.

If the production of soap has become more centralized, the reverse is true of marketing and sales. Ninety-eight girls sold soap across four suburbs in 2023. Under their contract they return 30% of what they earn to WAP to be re-invested in the business, but this has been resisted by some of the poorer parents and Constance is reluctant to apply pressure. This has yet to be resolved, but Trish’s calm presence and standing with the girls clearly helps.

Last year each girl earned on average $54 a month from their sales. This goes a long way in the neighborhoods but as Constance explained, so many parents are unemployed that the money usually pays for family essentials like food and school fees. Education costs on average $300 a year and is considered sacrosanct because it helps to keep girls out of marriage.

WAP will never cover all costs as long as the girls take the lion’s share of profits. But $26,716 was re-invested back into the business in 2023 and this covered a third of total costs. The biggest challenge comes from other inner-city soap-makers who sell at cut-throat prices. WAP has responded by using its Swiss vehicle and WhatsApp to reach out to rural areas. The WhatsApp list currently stands at 188 and more customers are signing up every week.

*

If the future looks bright for Clean Girl soap, the same is certainly true for Trish Makanhiwa. As her responsibilities have multiplied, Trish has blossomed into a confident, accomplished young woman who is adored by her peers. This was clear when we visited the four clubs last summer. Trish moved among the girls, gently inquiring about their situation, applauding their welcoming dances, collecting soap money and handing out chocolate.

Trish’s marriage to Alvin was, of course, the highlight of her year and her large circle of admirers saw to it that she would start married life in style. As she showed me around her kitchen, bright with a new fridge and other wedding presents, Trish confessed that she now earns more than her husband. It was said with a twinkle in her eye, of course.

-

Tribal Dress Code Tempts Mosquitoes

Leave a CommentVesthi has long been a traditional dressing style for the tribal people of Odisha. It consists of a long piece of cotton cloth that is wrapped around the waist and lower body.

This style of dressing suits the climate because it helps to reduce the heat around the body while the thin fabric keeps the wearer cool. It is also ideal for agriculture in the paddy fields because it allows the worker to keep dry while standing in deep water and work quickly (which helps him to lose excess weight!).

Finally, we should note that the Vesthi embodies masculinity and is viewed by some as a symbol of dominance and authority. More often than not the wear of the cloth will also sport a mustache, which he proudly twirls.

Vesthi has been part of tribal culture for ages, but this way of dressing can also lead to illness and disease, which causes mayhem in the community. Mosquito-borne diseases are particularly dangerous.

Paddy fields are full of stagnant water and serve as an excellent breeding ground for mosquitos who feast upon the workers. Lacking a proper dress code, the workers fall victim to diseases like malaria, dengue, filariasis, etc.

It seems obvious, but are the trial communities aware of the threat from these tiny insects?

Unfortunately no. Often, if a worker gets ill from malaria he will view it as a regular fever and send his family members to the paddy fields where they too will become infected. Of course, they do not need to plant and harvest rice to get stung by mosquitos and fall sick. Making matters worse, they are probably not aware of the risk and fail to seek medical help. This further worsens their sickness and can lead to death.

Is there any way to bring about a change? The answer is yes. Prevention may be better than cure, but the tribal dress code – to take one example – is deeply embedded in tribal culture. How do we help tribals to change dangerous habits and use safer methods?

Persuading someone to protect him or herself by covering their body doesn’t seem like a Herculean task. Really, how tough can it be to wear a pair of trousers instead of a piece of cloth? Well, it is hard! These tribal people may be welcoming and caring, but the moment you propound a new lifestyle, they go wild! It’s not about an article of clothing so much as their culture, which is intensely important to them. They identify through their culture and traditions and are proud of them.

How do we get around this? In my view, by appealing to young tribal people. While young tribals are also proud of their traditions, they are also keen to learn about the modern world. They understand how a style of living might also be dangerous. They are open to suggestions about how a safe lifestyle could go along with respect for the traditions and culture that are vested in their souls. They are also driven by the spark of curiosity. This can be a weapon in our fight against malaria.

-

Sand Painting and Wall Art Help the Fight Against Malaria

Leave a CommentThis impressive work of sand art was made by a prominent sand artist who lives in the coastal belt of Puri, Odisha State. It shows how mosquitos are our biggest enemies and silent killers, because they attack during sleep. The art only lasted 24 hours until it was washed away but it attracted a crowd and left a lasting impression!

The second photo, below, is of a wall painting in one of the ten targeted tribal villages named Kantabada. It shows a mother and her child sleeping under a mosquito net and keeping themselves safe from malaria.

-

Chariot of Awareness

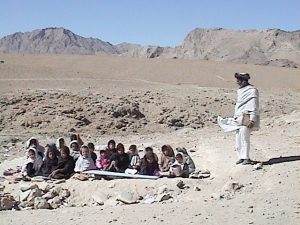

Leave a CommentMany tribal people in Odisha do not have access to formal education and this makes it harder to inform them about the risks associated with mosquitos. As a result, Jeeva Rekha Parisad must find a different vehicle – preferably one that unifies the entire community while also offering a narrative that will capture their imagination. That vehicle is the “Malaria Chariot.”

The chariot is a compact vehicle adorned with displays about Malaria, that include symptoms, methods of prevention, treatment options, and post-treatment care. These informative materials are presented in the local language, known as Odia, to ensure better understanding and accessibility.

As the chariot drives around the villages, people gather around to enjoy the exhibition, while at the same time learning about ways to combat malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases. People seem attentive and engaged as they digest the information on the chariot. They are contemplating how a tiny organism can be so dangerous and genuinely want some solutions.

By bringing people of all ages together under one roof, the malaria chariot also facilitates mass involvement. Those who are educated, especially schoolchildren, explain the chariot to those who are unable to read. This heightens the curiosity of their listeners and makes them determined to learn more. The chariot also gives us all a way to debunk misconceptions by providing evidence and using science. This invites follow-up questions from the audience, which are also met with rational responses.

Overall, the chariot has proved to be a colossal success and served as our main weapon in the fight against ignorance in the ten tribal villages. If our audience takes the message seriously, malaria can be beaten!

-

My Summer at Clean Ocean Access

Leave a CommentThis summer, as a part of my internship at Clean Ocean Access, I worked at summer camps to teach kids about our local environment and the importance of being environmentally conscious.

Every week, I would attend summer camps at the Newport Community School, the YMCA, and FAB Newport. During my time at these camps, we would teach lessons and play games with the kids. Some of the topics of our lessons included the watershed, composting, waste sorting, and noise pollution.

My favorite lesson we did was noise pollution at the Newport Community School. We started off the day with playing a game that involved echo-location. We assigned three kids to be our “dolphins”, this meant that they wore blindfolds and relied on their hearing to find their prey. After this, we told the rest of the kids that they were fish. And they all had a squeaky toy to make a sound with. The dolphins had to tag as many fish that they could hear as possible. The kids enjoyed this activity and had a lot of fun. After they all got the hang of it, we added “motor boats”to the game (these were kids that made loud boat noises). This represented noise pollution from boat traffic in the water. During the rounds with motor boats, the dolphins had a difficult time finding their food. At the end of the game, we had a discussion with all of the kids about why it is difficult for dolphins to find food due to noise pollution and how to prevent this. At the end of the day, the kids understood what noise pollution was and why it is bad for sea creatures.

Another one of my favorite activities we did was teaching kids about composting at the YMCA. We taught the kids that what we do on land affects the sea and the many benefits of composting. We also explained to kids the concept of worm composting and showed them Sarah’s worm bin. At first, the kids were grossed out because of the worms and their “poop”. But we explained to them that the worms helped create the compost because they eat food and poop out castings that benefit soil. At the end of this fun lesson, all of the kids picked up a worm and gave it a name!

Other days, we met up with camps on the beach and identified sea creatures. At Third Beach, we met up with a FAB Newport Summer camp and walked the beach with the kids. We ended up lifting up tons of rocks and looking for crabs. At the end of the day we caught 57 crabs! Majority of these crabs were Asian Shore Crabs, which are invasive species in Rhode Island. I also showed many kids a really cool trick: if you pick up a periwinkle and hum, it will come out of its shell. This is because the snail thinks the vibration is the tides going out, and they think they need to move closer to the water.

I had a ton of fun this summer and got to work with many different groups and organizations across Aquidneck Island. It was really great being able to teach kids in a fun way that helps them understand the important role of keeping our ocean clean.

-

Quilts Capture the Terror and Heroism of COVID-19

Leave a CommentQuilts Capture the Terror and Heroism of COVID-19

-

Monsoon Nemesis

Leave a Comment

Being a tropical nation, India flourishes in lush greenery. It is also blessed with ample rainfall, which provides a lot of space for agricultural and other farming activities. This is what the people of India have been doing for centuries.

The state of Odisha is no exception. With an average yearly precipitation over 130 cm. Over 75% of our rains come in the months of June to September.

The land is home to many farmers, who are heavily dependent on rain because rice requires paddy and paddy fields need a lot of water. But most farmers live in rural and tribal areas and cannot afford farming technology which would help with irrigation and make their lives easier. The monsoon is their only real source of water. So it is not surprising that the first rains are welcomed with pomp, joy and many festivities. It is at the merriest of times.

At the same time, people are oblivious to the grave danger brought by rain. While the monsoon means fertility, it also brings a surge of infections and diseases.

Urban communities are sensitized to the threat from water-borne diseases. They know the meaning of prevention and can seek medical treatment provided by the government. Rural areas, however, are more exposed to untimely medical ailments and have less possibilities for treatment. And those most affected are the tribal communities.

These communities are neglected by the government. Lacking medical support and stern guidance on prevention they are unaware of the diseases that threaten them during the monsoon. This can lead to death.

Tribal hamlets are mostly located in forests, a part of which is used for agriculture. This dense jungle, flooded with water, is a perfect environment for mosquito-borne diseases. As a result, tribal communities have the highest number of infections from malaria, dengue, and filariasis. People in these communities are completely unaware of these life-threatening illnesses carried by mosquitoes.

The lack of information also means that tribal people do not consider strategies to address the threat, or adapt their way of live. They are blindfolded and unaware of the grave danger that surrounds them.

-

Raibari Singh – Perseverance and Hope Amidst Adversity

Leave a CommentRaibari Singh, a 24-year-old married woman, lives in a small dwelling in Krushnanagar village. She shares her humble abode with her husband, Ram Singh, her 79-year-old mother-in-law, and their 3-year-old son.Ram Singh has supported his family by working as a daily labourer, heading out for work each morning at 5 o’clock and earning Rs 400 ($4.8) a day. The family’s income is Below Poverty line (BPL), and Raibari supplements their finances by venturing into the forest to gather wood and other forest resources. In addition, she also plants rice in the nearest village, earning Rs200 ($2.4) per day.

With all these responsibilities, Raibari faced a lot of challenges during her second pregnancy. When she was seven months pregnant, she began experiencing symptoms such as fever, nausea, vomiting, and chills. Despite her discomfort, Raibari initially dismissed these symptoms at the urging of her mother-in-law and well-meaning neighbors who suggested that such experiences were typical during pregnancy.

The family, including Raibari, chose to neglect the symptoms for almost 15 days. Their attitudes changed when the JRP team reached her house and told her about malaria – its symptoms and remedies. Over the next three days, however, Raibari’s condition got worse. She suffered a high fever of 104 degrees and sudden bleeding. This reminded her of her menstrual cycle and scared her a lot.

The JRP team had been following Raibari. and suggested that she should visit the hospital and get a thorough examination. Without hesitation, her husband promptly took her to the Community Health Centre (CHC) in Mendhasala. She was admitted following a comprehensive assessment.

Subsequent tests found that Raibari had contracted the malaria parasite Plasmodium Falciparum, which had also affected her unborn child. Tragically, the child was lost just a day before this diagnosis. Raibari was admitted to the hospital for another month to receive the necessary medical care and treatment.

In spite of her terrible loss, Raibari had kind words for the JRP team: “I Sincerely thank you to the JRP teams, especially the project coordinator, for their eye-opening information regarding malaria and its prevention.”

-

Humming to the Periwinkles

Leave a Comment

This summer, as a part of my internship at Clean Ocean Access, I worked at summer camps to teach kids about our local environment and the importance of being environmentally conscious.

Every week, I would attend summer camps at the Newport Community School, the YMCA, and FAB Newport. During my time at these camps, we would teach lessons and play games with the kids. Some of the topics of our lessons included the watershed, composting, waste sorting, and noise pollution.

My favorite lesson we did was noise pollution at the Newport Community School. We started off the day with playing a game that involved echo-location. We assigned three kids to be our “dolphins”, this meant that they wore blindfolds and relied on their hearing to find their prey. After this, we told the rest of the kids that they were fish. And they all had a squeaky toy to make a sound with. The dolphins had to tag as many fish that they could hear as possible.

The kids enjoyed this activity and had a lot of fun. After they all got the hang of it, we added “motor boats”to the game (these were kids that made loud boat noises). This represented noise pollution from boat traffic in the water. During the rounds with motor boats, the dolphins had a difficult time finding their food. At the end of the game, we had a discussion with all of the kids about why it is difficult for dolphins to find food due to noise pollution and how to prevent this. At the end of the day, the kids understood what noise pollution was and why it is bad for sea creatures.

Another one of my favorite activities we did was teaching kids about composting at the YMCA. We taught the kids that what we do on land affects the sea and the many benefits of composting. We also explained to kids the concept of worm composting and showed them Sarah’s worm bin. At first, the kids were grossed out because of the worms and their “poop”. But we explained to them that the worms helped create the compost because they eat food and poop out castings that benefit soil. At the end of this fun lesson, all of the kids picked up a worm and gave it a name!

Other days, we met up with camps on the beach and identified sea creatures. At Third Beach, we met up with a FAB Newport Summer camp and walked the beach with the kids. We ended up lifting up tons of rocks and looking for crabs. At the end of the day we caught 57 crabs! Majority of these crabs were Asian Shore Crabs, which are invasive species in Rhode Island. I also showed many kids a really cool trick: if you pick up a periwinkle and hum, it will come out of its shell. This is because the snail thinks the vibration is the tides going out, and they think they need to move closer to the water.

I had a ton of fun this summer and got to work with many different groups and organizations across Aquidneck Island. It was really great being able to teach kids in a fun way that helps them understand the important role of keeping our ocean clean.

-

Witchcraft and Malaria

Leave a Comment

Jhari (photo) had transformed the area around her cottage into a work place, diligently removing husks from rice and cooking a vegetable stew on an open wood stove. Old age and smoke from the burning embers made it hard for her to see. But the sunlight was strong and this helped her to use a sieve in cooking.

As I walked up to her, Jhari was humming a folk tune in a melodious voice. A sense of peace came over me but it was mixed with melancholy. The song was about Krishna, a deity revered by Hindus, and this eminent lord’s descent into the shallow waters of the abyss after being struck by an arrow, followed by his death.

I wondered why this old lady was singing such a tragic song, associated with trauma and pain. As we sat and talked I began to understand.

Jhari has seen a lot of misery in her life since her husband died early in their marriage and left her alone with her newborn child Reena. Jhari embraced the role of a single parent and set about earning a living without any concern for the social stereotypes stemming from her tribal background. One of the happiest moments occurred when her daughter Reena married Bharat Nayak and gave birth to two children, Jogendra Nayak, 14, and Mousumi Nayak, 8.

Reena was living a happy life when catastrophe struck during the monsoon. Bharat suffered came down with a terrible fever. Reena and Jhari assumed that Bharat’s fever was caused by a virus and took no action, thinking Bharat would be fine in a few days. But his condition worsened. His fever grew worse and he suffered from fatigue, nausea and a loss of appetite. A few days later, he began to have seizures.

Jhari and Reena assumed that an evil spirit had entered Bharat and took him to a sorcerer living on the outskirts of the village. This witch doctor claimed that Bharat had been plagued by an evil force that had to be removed. He took Bharat in for 3 days and performed a series of rituals that were unorthodox, cruel, and terrifying.

The sorcerer boasted loudly that he had removed the evil entity. But by the third day Bharat could no longer tolerate the pain and trauma and passed away in the afternoon. Incredibly, the villagers were still hailing the wonders performed by the sorcerer.

But four people were standing near the body of Bharat whose lives had just been devastated. When they took the body to the medical facility to get the death certificate the doctors stated that the cause of death had been malaria and had nothing to do with witchcraft. Questioned by the distraught family, the doctor explained that malaria is caused by the bite of a tiny mosquito.

However, his death could also be blamed on witchcraft……..

-

Bringing Green into the Settlements and Vice Versa

Leave a CommentIn Nairobi’s informal settlements, arable land is scarce. Most of Shield of Faith’s project participants use the little land they have available to them to build their kitchen gardens. This often includes carving 5-liter jerry cans into vertical towers to plant spinach and other greens. While these gardens are able to meet approximately 30% of most members’ vegetable needs, other members are forced to go without due to a lack of space.This is where Stella’s demo farm comes in.

Out in Kajiado, about one hour outside Nairobi lies Stella’s plot of land, waiting to be cultivated. While it may not look like much now, with a bit of labor this land presents huge potential. Under Stella’s guidance, Shield of Faith’s ladies will be able to drive out to this farm twice each month to tender and harvest their own crops. This demo farm has the ability to fulfill way more than 30% of members’ vegetable needs; it could fulfill all or almost all of them. As a result, the women would save exponentially on their grocery bills, diverting the money saved to pay for rent or their children’s school fees.

Another foreseen benefit of the demo farm is the capacity to grow uncommon yet highly nutritious vegetables that wouldn’t be found elsewhere in Kibera. As mentioned in one of my previous blogs, the project recently ventured into growing Chinese cabbage in one of the project participant’s communal gardens. Although hesitant to try the previously uneaten green, Shield of Faith member Vena was brave enough to take some home with her, and she loved it. By introducing members to new vegetables, the project adds vitamins and nutrients to their diets and those of their families. Also, it makes members more resilient to supply shocks of traditional crops. As I witnessed last weekend on a site visit to Kajiado, developing the demo farm will allow Shield of Faith to scale this approach.

While my fellowship and time in Nairobi have unfortunately come to an end, visiting the demo farm was a great way to finish my fellowship. As I reflected on the insights I gained from Stella and Shield of Faith’s members over the summer, I was able to visualize the future of this project. Already, each of Shield of Faith’s 20 members acts as an Environmental Ambassador in their community by conveying the benefits of composting and organic gardening to their friends and neighbors. If the women are able to bring more and more organic green vegetables into the settlements, sooner or later, those in positions of power are bound to take notice.

-

Working the Newport Oyster & Chowder Festival

Leave a CommentAs a part of my internship at Clean Ocean Access, I have helped out at a couple of community events as a “Green Team” member to help people sort their waste. On May 21st, I worked at a waste station at the Newport Oyster & Chowder Festival in Bowen’s Wharf.

This festival in particular was important for COA to be at because over ten thousand people attend it annually and around fifteen thousand oysters are shucked; a recipe for a lot of food waste.

At the waste stations, there was a recycling bin, landfill bin, compost bin, and a special bin for the oyster shells to be placed in. The oyster bins were to be collected and brought to the Nature Conservancy. From there, they let them curate in the Great Swamp, a wildlife management area in Rhode Island, for six months and then brought back to oyster farms to reuse.

From the start, the event was packed. People were flooding in and out of the wharf buying food and drinks from vendors. It was hot, loud, and people just wanted to quickly get out of the area once they were done eating.

People would quickly walk to the waste station I was at and dump everything into one bin before I could even explain to them what to do. Oftentimes, people did not even think I was there to help and they just thought I was a random girl standing next to the trash with gloves on, picking plastic bottles out of the compost bin.

So, I began to take more charge in front of the waste station, stopping people in their tracks before they could even think about throwing their waste in a bin.

This was a little more difficult than composting at my school, as we only composted food waste. Here, there were many different things that could go into the compost like cardboard and compostable cups. So, I had to be very specific when I helped people sort their waste. Instead of one quick dump that would only take 5 seconds, it often took people up to 45 seconds to thoroughly dispose of everything properly.

Some people were aggravated, and composting was the last thing they wanted to do. But others thought it was a great idea and thanked me for being there. Still, the waste was properly sorted and that is all that mattered.

When my shift was over, I walked out of Bowen’s Wharf and saw endless bins packed full of oyster shells. It was crazy to think that all of these would have been brought to the landfill if we did not help people sort out their waste. It was really cool to help out at this festival and sort waste on a bigger scale compared to my high school.

-

Passions Can Lead to Change

Leave a CommentThe environmental crisis worsens as time passes, and it seems like there is no hope. News stories about wild fires, polluted air, flash floods and so many more harmful things happening to our planet are frequently seen on our TVs and feeds. How will me using a paper straw at starbucks help these issues? How will me riding a bike rather than my car to work help these issues? How will me doing anything help these issues? How…do we continue to have this mindset? Why are we so pessimistic with this issue?

We’ve been overwhelmed by the huge crisis at hand, that it’s easy to lose sight of what’s important: we are not powerless. I know It may seem like the solution is in the hands of these big corporations that are doing the most harm, but we are not without responsibility as well. These little changes may seem pointless, but they’re not. A little really does go a long way. But if you want to do more than just the little things, what can you do? If you’re not an environmental activist, how could you make any big impact? Well how do we do most things? We try.

Whether your passion is teaching, coding, music, art, or anything, you don’t have to feel like you can’t assist this movement in some way. I have a passion for media production specifically through film making, graphic design, and photography, and I used to think I didn’t have the right skill set to make real change, but I do, we all do.

At my school we focus on developing projects throughout the year through our “real world learning”, or learning through internships. When it came time for me to look for a new internship my sophomore year, I solely focused on finding an internship related to video production and film making, because I knew I was passionate about those things. My search wasn’t going great, so I went to my advisor for advice, and I think what she told me can be applied to more than searching for an internship. She told me to stop limiting my search for sites that were directly related to my interest, and to start searching for sites where I could apply my interest.

My search then went from looking for film production companies, to looking at every local business and organization I could contact in my community. This led me to Clean Ocean Access.

At first, I was reluctant to join Clean Ocean Access. It was a non profit organization that focused on environmental advocacy through programs, events, campaigns and more, and I didn’t see a way I could be of help to their organization. Although I was passionate about activism, I only focused on social injustice issues. I had never seen myself as a big environmental advocate, more as a “good civilian who could support the movement”. Regardless, I listened to my advisor’s advice and gave Clean Ocean Access a shot, and I couldn’t have made a better decision.

My first day I immediately hit it off with my mentor and I had already developed a project idea for that trimester. I would go onto organize a fundraiser for my school’s composting program. I called the fundraiser “Carving for Compost”, and the idea was that I’d contact farms around my state to collect extra pumpkins that were grown during the Halloween season that would otherwise go to rot for a pumpkin carving fundraiser. This derived from the fact that many farms in America mass produce pumpkins for Halloween, and most of them go to waste in our landfills.

Through this project I harnessed my skills in media production by creating posters, infographics, presentations and more to advertise the fundraiser. This is just one instance out of so many that helped me realize that there were so many ways my skill set could be used to help environmental advocacy efforts.

Giving Clean Ocean Access a chance not only showed me how my passions could make real change in the environmental movement, but it also helped me find a passion for environmental activism, and to see how I could connect it to my existing interests. You can also find ways to harness your passions to assist the environmental movement, or any movement for that matter. No matter how small the effort may seem, it isn’t pointless. There is every reason not to do something, but don’t let those reasons blind you from why you should at least try. Your passions can lead to change.

-

Textiles Are a Woman’s Best Friend

Leave a CommentHow does one seemingly mundane pillow, rug, or bedspread translate into a family’s meals for the week and a heightened position for women in the household? In Kenya, the significance of the textile industry is seen all throughout the country, from the crowded stalls in Nairobi’s Maasai Markets to the vendors lining streets along the coast. This industry has one of the highest appeals to foreigners visiting Kenya. Oftentimes, when I walk past a textile shop, I find all or almost all employees to be women. Indeed, the textile industry seems to be predominantly made up of women.For women from low-income backgrounds, the textile industry can present more than just a source of employment. It can also present them and their families with resiliency.

I learned the significance of the textile industry for women’s economic empowerment when I visited the coastal city of Mombasa this past weekend. There, I booked a guided tour, and my tour guide Humphrey took me to the Imani Collective workshop. Humphrey explained to me the purpose of the American-backed project: to empower local female artisans through paid employment and market support. At the entrance, I saw signs with the words “This is empowerment.” Upon entering, I was surprised to see striking similarities between this project and Shield of Faith’s embroidery activities. Despite Mombasa and Nairobi being on opposite ends of the country, separated by a 6-hour long train ride, the ideas behind women’s economic empowerment are the same. There were several looms, where artisans weave cotton yarn into intricate patterns, producing all sorts of gorgeous fabrics. Just one week prior, I visited a woven textile workshop in Nairobi’s Industrial Area with Shield of Faith’s members to gauge opportunities for paid employment.

Seeing the success of the Imani Collective in Mombasa confirmed the fact that the textile industry does serve as a viable and sustainable source of employment for women. It also allows women to develop their skills and pay off some of their household expenses. Speaking with Shield of Faith’s members at the textile workshop, I learned that some of them have used the money generated from the project’s embroidery activities to pay their children’s school fees or buy beds for themselves and their families. Shield of Faith’s members already have strong embroidery skills. If given the chance to obtain employment in the textile industry, with the opportunities it presents, their potential is unlimited. Shield of Faith understands that. And it’s clear, from visiting the Imani Collective in Mombasa, that others around the world understand it, too.

-

Oh, How I Love Being a Woman

Leave a CommentIn honor of the Barbie movie coming out last week, I want to take the time to reflect on the power of women.This past weekend, I accompanied Stella and Shield of Faith’s members to Nairobi’s Industrial Area, where each woman demonstrated her embroidery skills in the hope of obtaining employment in a textile company. As I sat at the table surrounded by all of these incredible women, I marveled at their sisterhood. Jokingly, a few of the ladies remarked that I was young enough to be their daughter. At that moment, I realized something. I realized that sisterhood and motherhood can coexist in female relationships. And somewhere within that nexus lies the strength to endure all.

Take Esther for example. Esther, one of Shield of Faith’s members, is simultaneously the most fearless and warm-hearted person I’ve ever met. From the day we met, she asked me to come to her house so she can cook me dinner. Esther lives in Githurai, a settlement 30 minutes northeast of Nairobi CBD. She lives alone with her three daughters, one of whom has albinism. In Kenya, mothers of children with albinism face discrimination within and outside the family. When Ruth’s aptly-named daughter Hope was born, the nurse offered to buy her. People with albinism are sometimes used in harmful rituals, and it’s possible the nurse wanted to capitalize on this seeming “opportunity.” Along with outsiders, Ruth faced discrimination from her husband and in-laws, who wrongly accused her of having an affair with a white man. At the beginning of this year, she used the money she saved up from the composting and embroidery projects to pay rent on an apartment and leave her abusive husband.

Unfortunately, Esther’s story is very similar to the other mothers of children with albinism. They’ve all faced many challenges in life, but they’ve found solace in knowing that they aren’t alone in their experiences. The other week, Stella and I were talking about womanhood, and I remember saying that, as women, we naturally bottle things up. When we eventually make the brave choice to open up about our challenges, we often find that others have experienced similar things. Sitting at the table surrounded by all these women, I admired their solidarity, and it reminded me to use my experiences as a bridge connecting me to my fellow sisters rather than as a wall alienating me from my greatest source of strength.

In terms of Shield of Faith’s activities, the quote on the back of Rehema’s shirt (pictured below) accurately captures our mission: “The goal isn’t women making more money. The goal is more women living their lives on their own terms.”

-

Dolphin Clean-Up!

Leave a CommentI completed my first week of providing summer camp education at Clean Ocean Access. In the morning, I was able to help with a beach clean up at Easton Beach with Immaculate Conception Church’s summer camp. Later, I educated children at a Aquidneck Island Day Camp about echolocation and noise pollution.

I did the beach clean up with the help of a great group of elementary to middle school children. The children were very interested in the beach clean-up. They were very excited about getting a trash grabber stick (which I was passing out), and using it to pick up litter. When it came to the clean-up, they were very efficient and collected over 23 pounds of trash. Some interesting items they found were shoes and sunglasses. However, frustratingly, they were unable to get a rope that was stuck in the ground. We had a lot of fun!

In the afternoon, I educated children at Aquidneck Island Day Camp about echolocation and noise pollution through two games. In the first game, children formed groups of two, and one child would be blind-folded while the other got a clicker. Then the child with the clicker would guide the blind-folded child through cones by communicating through a series of clicks.

The second game was similar to Marco Polo, but with dolphins and fish. Initially, the dolphins were able to find the fish quite easily. However, after “oil tanks” (the children would make a lot of noise by clapping) came into the ocean, they would make it a lot more difficult for the dolphins to find the fish. The day was split into younger kids (ages 4-7) and older kids (8-12).

We first had the younger children (ages 4-7). They sometimes had a hard time following directions and some of them didn’t know their right from left (which they needed for the first game). Still, they all had fun. There were two very endearing sibling “dolphins” who would hug when they ran into each other. Several times, the brother remarked “she’s my sister”.

Next, we had the older group (ages 8-12). The older group was much smaller and they better understood echolocation and noise pollution. They knew their right from left, so the first game went a lot more smoothly! However, during the second game, two of the kids bumped heads and began to cry, so we had to promptly stop the game.

This first week allowed me to learn the ropes of doing summer camp education. I think that I should improve on being a bit louder and assertive, since the children can have a difficult time listening to directions. I also think that I should work on presenting the information more clearly to younger participants. Overall, I had a lot of fun and I can’t wait for the next time!

-

Progress Against Plastic

Leave a CommentWhile in the U.S. plastic grocery bags are ubiquitous in almost every household, you won’t find them here in Kenya. In 2017, the Kenyan government banned all single-use plastic carrier bags for retailers. This means that in the local QuickMart, Carrefour, or Foodplus grocery stores, your groceries are bagged in reusable shopping bags, which are sold to you at a small fee. A small price to pay for a big impact.Unfortunately, the use of single-use plastic carrier bags did not immediately cease following the ban. According to the Kenyan government’s assessment of compliance, only 80% of individuals complied with the ban in 2019, rising to 95% in 2021. Organizations such as the Kenyan Association of Manufacturers opposed the ban on the grounds that it would eliminate jobs. Even today, you are still able to spot the plastic bags across Nairobi, as I did last Saturday in Kibera.

In Nairobi’s informal settlements, vendors are able to slip under the radar. A 2019 study found that only 30% of those interviewed in Kibera supported the ban on plastic bags, compared to 60% in the affluent Nairobi suburb of Karen. While conducting site visits to Shield of Faith members’ homes last weekend, Stella, Iain, and I stopped to purchase sugarcane from a local vendor. I was surprised to find that the vendor was using plastic carrier bags, having not seen a plastic bag since I arrived in May. Stella, unfortunately, was not surprised. She commented that bags such as the ones pictured below are often illegally brought into Kenya from neighboring Tanzania. In Kibera and the other informal settlements, these bags often end up strewn along the side of the road or in the massive waste heaps where residents dispose of their household garbage. More action is needed by all stakeholders to eliminate these bags.

The improper use and disposal of plastic bags have countless environmental consequences, with one of the most pressing being the consumption of plastic by animals and subsequent contamination of the food supply. Just this year, the Kenyan public interest group Centre for Environment Justice and Development found extremely high levels of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in chicken eggs, with levels higher than 111 times the EU regulatory amount. Similarly, the body found that a Kenyan adult eating a chicken egg from certain hotspots, including Nairobi’s Ngara Market, “could be exposed to a dose of toxic chemicals that would exceed the EU daily safety limit for more than 250 days.”

Shield of Faith stands at the forefront of this issue by promoting a culture of recycling and proper waste management in Kibera. Making expert use of 5-litre jerry cans, formerly used to store soap or oil, Stella reuses the containers to create planter boxes and tower gardens for growing fruits and vegetables. In fact, most of Shield of Faith’s members reuse 5-litre jerry cans in their gardens one way or another. With such high demand among Shield of Faith’s 20 members, Stella purchases empty jerry cans from local restaurant owners and housekeepers, thus inviting them into the project as indirect beneficiaries. Gradually, each one of the project’s direct and indirect beneficiaries becomes more conscious of their plastic use and encourages recycling in their own households and those of their neighbors. One restaurant owner in Kibera, Quinter, saves up her jerry cans for Stella to purchase. In the end, Quinter earns a few hundred shillings, Stella gets her jerry cans, and plastic that would have likely been dumped in Kibera’s trash heaps is instead used to grow something beautiful.

-

The Many Faces of Nairobi’s Informal Settlements

1 CommentFew people are familiar with Nairobi, let alone its informal settlements (or “slums,” what have you). For those who do have some knowledge of Nairobi, it’s likely they’ve heard of Kibera. Famously known as the “biggest slum in Africa,” this informal settlement has a population of a quarter of a million people. Its homes are constructed out of sheet metal and mud, and its residents lack any sort of formal rights to their land. Many of these families have been essentially “squatting” on the land for generations.What many people fail to realize, however, is that Nairobi has over 150 informal settlements, all without government services. Kibera, as the settlement with the biggest population, naturally attracts attention from foreign donors. Over 300 NGOs are currently operating in Kibera.

Compare this to the informal settlement of Huruma, and the picture is vastly different. Between 2000 and 2020, population density in Huruma increased faster than in Kibera with 766.98 residents per hectare compared to 475.27. The result of this surge in population density is overcrowding in Huruma’s decrepit multi-story cement buildings, where families fill single-room homes with no running water. Arguably, these housing structures are more dangerous than the single-story sheet metal homes constructed in Kibera. In 2016, an apartment building in Huruma collapsed, killing 52 people. The building owner had rented out 100 rooms, even though the government declared the building unfit to live in. This is all to say that in Nairobi’s other informal settlements, living conditions are just as bad, and in some cases even worse. Yet, they fail to attract a fraction of Kibera’s donor attention.

Having lived in Huruma for 10 years, Shield of Faith member Ruth occupies a small one-room apartment with her children. On Sunday, Ruth invited me, Stella, and AP’s Executive Director Iain into her home and shared her story with us. Upon entering the building, we each had to turn on our phone flashlights to navigate the dark and narrow stairwell up to the fourth floor. Every day, Ruth walks up and down these stairs carrying 20L containers of water, which she has to purchase for 10 Kenyan shillings, the equivalent of 7 US cents. She admitted that it was a hard life, but she was grateful to us for coming to witness her everyday experience. I will forever be grateful to Ruth and her daughter Sharon for opening their hearts and their home to us.

While not each of Kibera’s 300 NGOs is efficient (I’ve heard complaints that they aren’t), the fact that they’re there says something. These NGOs have the potential to impact the lives of someone like Ruth, but we won’t know until or unless something changes about the NGO landscape across Nairobi’s informal settlements.

-

Diversifying Diets in Kibera

2 CommentsBefore Stella Makena kickstarted Shield of Faith’s gardening and composting project in the Kibera informal settlement, many of the project’s members had never heard of, let alone tasted, Chinese cabbage and strawberries. Today, their gardens are producing these fruits and vegetables in bounty.In Kibera, where food insecurity is high, many of the settlement’s residents rely on whatever produce they can afford at the numerous informal produce stands or at Toi Market. In this open-air space, hundreds of vendors compete to sell produce, second-hand clothes, and even furniture. Unfortunately, this market recently suffered from an electrical fire just over three weeks ago. One trader reported to Kenya’s Pulselive media outlet that a little over 3,000 stalls were razed in the fire. Not only did this deeply affect all of the vendors in the market, thus leaving a deep scar on the settlement’s informal economy, but it also meant that those who relied on the market to purchase their fruits and vegetables now had to seek alternative, and sometimes more expensive, sources.