The saying that it takes a village to raise a child has never proven to be so true until my recent visit with four orphan girls (ages 11-13) who are beneficiaries of the Kakenya Dream Organization’s (KDO) financial support and mentorship.

Within Maasai culture, men are typically the bearers of money, land, cattle, property, and are permitted to take more than one wife. It is often common for a child to have several stepmothers and stepsiblings. In some instances, a father may be gone for several weeks or months, while he fathers the children of his other wives. Often, these polygamous relations can result in husbands and fathers abandoning their other wives and children. An “orphan” as we know it in Western society therefore takes on a different meaning in Kenya. It often means paternal abandonment, despite other family members being a part of the child’s life.

My recent visit to one of our girls home brought reality to what girls go through to achieve their education.

“Thank you for helping me,” 13 year-old Nelly says after wiping away her tears in an hour-long interview I was conducting. Nelly is one of several KDO beneficiaries. She receives guidance and financial support to supplement what her family members are unable to provide. Nelly’s parents divorced when she was born. She has three sisters and one brother. She is the second to last child. Nelly is from Sikawa, about an hours drive south of Enoosaen. She lives with her youngest sister and her older brother. Her other two sisters live with her father and have been forced to undergo female genital cutting (FGC).

I have repeatedly heard teachers and parents say, “A woman never forgets where she comes from. If you educate one girl-child, you educate a whole community.” This saying has been fixed in my mind throughout my fellowship. Its truth can be best understood by speaking to those who benefit the most from the support of KDO. I was able to stay with Nelly at her home during the half-term break as a part of a series of interviews I was conducting with some of the KCE girls.

Just five minutes from the main swampy road, a small community river intersects with a narrow muddy path where KCE teacher, Francis Kisulu, and I walked to the quaint clay home of Nelly’s family.

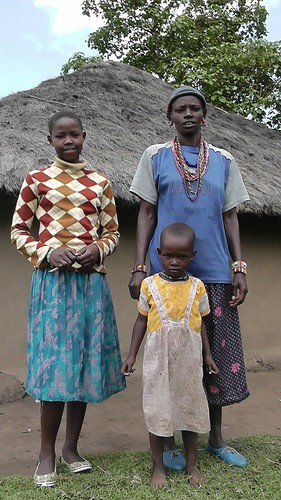

“Nelly!” Francis called out. No more than a few seconds passed before Nelly’s little sister, Nashipai, a two-foot tall girl in a bright yellow-topped dress, stood at the doorway entrance of their mother’s home. Not yet fazed by the shyness of older girls, Nashipai ran up to greet us.

She bowed her head as the traditional Maasai greeting. “Takweya,” I say as I touch the top of her head, Francis quickly did the same.

Their mother had just walked up to the neighboring field to milk cows. We were given small stools, underneath the shade of a tree near their home, as we prepared to interview Nelly. With the help of Francis to translate from Kiswahili to English, I was able to freely interview her.

In her own words we were able to capture a glimpse of Nelly’s life:

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” I say.

“I want to be a police.”

“Why?”

“I want to maintain order and peace in our country.”

“Have you always wanted to be a policewoman?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have a good relationship with your mom?” I ask.

“Yes…She likes me, and she likes to support me in my education,” Nelly says quickly and softly.

“Has she always supported your education?”

“Yes.”

“What about your father?”

The mentioning of her father alone triggered tears in her eyes. She clasped her hands together and held them in front of her face.

“He doesn’t support me…,” Nelly whispers under her choked up breath.

I wait for her to breath. Nashipai innocently watches her sister hunched over crying. Her brother, Gideon approaches her and asks if she is okay. She giggles and clears her throat out of embarrassment.

“Why doesn’t he support you? Is it against his value system?” Girl’s education in Maasai culture is typically not favored by the male figures of a girl’s family.

“Yes…he dislikes me,” Nelly replies in a soft voice.

Nelly tells us that her father feels resentful since his divorce with her mother. Unlike her father, Nelly’s mother has been very supportive of Nelly’s educational pursuits. We also learned that it was her brother who encouraged her to apply to KCE. Since her enrollment in KCE she has been able to focus on her studies.

“In boarding school I can learn at night,” Nelly says.

“Do you feel you are getting a lot of support that you did not have in Sikawa primary?”

Nelly is silent for a minute before she answers, “At Enkakenya I can go to ask the teacher questions I don’t know.”

“How has going to Enkakenya changed your life?”

She answers in Kiswahili; her hands cover her mouth while she sobs and talks. Francis says to me, “She says that they pay for her school fees and provide her with the school uniform.” At that moment I hugged her and said, “You are very brave and strong…thank you.”

This is one interview in a series that profile the impact that the Kakenya’s Dream Organization has made in these young silenced lives. Young girls such as Nelly have been given the opportunity to focus on their education, avoid FGC and being married off. A girl-child without a father often becomes a financial burden to other family members who have their own daily challenges.

Though difficult to change, KCE works to reshape Maasai culture by nurturing its young women through the use of the same tools it does their boys. Girls are thus given an opportunity to participate in the human capital of their communities. In my experience here so far, I have learned that KCE has become more and more a prominent part of this village working to raise its children and in doing so, foster a healthy future especially for those less fortunate.

***The children’s names have been change to protect their identity***

Posted By Megan Orr

Posted Aug 1st, 2012