This series of blog posts tells the stories of the people affected by chhaupadi, with a view to exploring different aspects of the practice in depth. All testimony and photographs in this series have been made available with the relevant subject’s express consent. A general introduction to chhaupadi is available here and there are more photographs in this album.

“I try to talk with my friends and peers about the dangers of chhaupadi, both inside and outside school,” says 15-year old Manish Sapkota. We are sitting on the porch of one of the dwellings on the main market street of Gutu village, Surkhet District. The house is made of wood pillars covered with a mud rich in clay, leaving the floors and walls with a smooth, even finish. Manish, who lives next door, is quiet for a while and then adds “my friends usually listen, but their parents don’t.” After another pause, “whatever happens, I will keep raising awareness, because such a bad practice needs to end.”

Market Street in Gutu village, Surkhet District.

Manish has been chosen to participate in the “peer educator” program of the Centre for Agro-Ecology and Development (CAED). Every year, CAED convenes a group of bright adolescents with a strong commitment to social justice for a comprehensive “life skills” training session. “During this annual training, we learn about sexual and reproductive rights and health, principles of gender equality and related social justice issues such as child marriage,” Manish explains with enthusiasm. “We also learn how to communicate and advocate for our rights in a culturally-sensitive way, so that we can understand how to talk about these difficult issues in our communities without being afraid.” CAED reinforces these annual trainings with quarterly meetings, to help the peer educators brush up on what they have learned.

Dipika Shrestha and Dila Kadel on their way to meet a group of peer educators. Dipika works for CAED and Dila, who conducts training sessions for the peer educators, works for a local partner organization (Women’s Association for Marginalized Women).

When asked what the peer educators do with such newly-acquired skills and knowledge, Manish explains that their core duty is to make it possible to start meaningful conversations about taboo subjects in their respective villages. Naturally, the peer educators are inclined to start having these conversations with their friends first. The result, as followers of this blog will recall from the stories of Sunita Dhungana and Balika Bik, is that young members of the community are empowered as agents of social change as they acquire the confidence to discuss very sensitive religious and superstitious practices with their parents. Some, such as Balika, have even managed to convince their families to allow daughters, sisters and mothers to sleep inside while they are menstruating.

A mural painted by the students of the secondary school in Gutu depicting a man who experiences the dangers and superstitions surrounding menstruation. In the series of images (from left to right), he begins menstruating, is forced to sleep in the chhau goth (hut), is given food by relatives (who are not allowed to touch him) and sees a poisonous snake near the hut.

“We also learn very practical things,” says Manish. “For example, in last year’s training session, I was taught how to make reusable sanitary pads.” Feminine hygiene products are often unaffordable for members of Manish’s community, and, without them, girls find it difficult to attend school when they have their period. “Now I regularly teach my friends how to make these reusable pads, which make everyone’s lives much easier.”

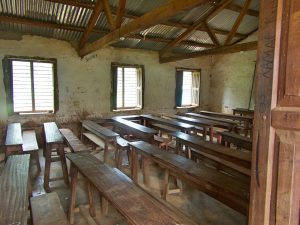

Classroom in Gutu village.

I wonder how my readers picture Manish, and whether they would be surprised to discover that he is a boy? Have you ever been introduced to a young man, in the place where you live, who spoke of periods and pads and the stigmas surrounding menstruation—without seeming uncomfortable in the slightest—during your first conversation?

Manish Sapkota

Manish’s courage to breach these topics within his community is a testament to the success of the peer educator program. It proves that it can instill the drive for social change among all members of the younger generation—even those who are not themselves subjected to such gender-based discrimination. With such widespread condemnation of the shame and harm that women suffer as a result of chhaupadi among the future leaders of the community, it can only be a matter of time before the inhabitants of Gutu village put a definite end to it.

With some families already abandoning the practice, the prospects of escaping chhaupadi are looking brighter for these girls than for the generations that came before them.

Posted By Caroline Armstrong Hall (Nepal)

Posted Aug 3rd, 2018

4 Comments

Corinne Cummings

August 3, 2018

Hi Caroline, fantastic interview! I loved the idea of interviewing a young man on the issue of chhaupadi — it was brilliant to include Manish. I was so curious to hear what the men in the village felt about this problem. Thanks for the insightful information. I learned a lot from this blog post. The idea of reusable sanitary pads is great — it saves money and it’s better for the environment too. Industrialized nations should also be pushing for reusable sanitary pads. Keep up the great work, Caroline. I am looking forward to reading more about the community members in western Nepal and their thoughts on the practice of chhaupadi. Take care. Best, Corinne

Princia Vas

August 6, 2018

Great job on including a young boy’s perspective on chhaupadi. Its interesting to see how the younger generation/millennial males are passionate in supporting this cause 🙂

Ali

August 6, 2018

Caroline, great post. Manish seems awesome and his courage is truly inspiring. Thank you for sharing.

iain

August 12, 2018

What is the rationale behind winning over men and boys like Manish? Surely, the main defenders of chhaupadi are women – ie mothers and grandmothers? Have you met any fathers who are taking a strong stand?