Lelmolok Center is surrounded by cornfields and the distant, rolling hills of Kenya’s western highlands. The earth is red and the abundant crops are often freshly painted by rainstorm. This is not a setting in which you would expect to find internally displaced people (IDP’s), living in leaky tents with barely enough food to survive. When we think of temporary communities sprung from violent displacement, we tend towards images of inhospitable deserts – not verdant farmland just outside of sizable cities. Refugee camps are often located in harsh settings because (and this is oversimplified) the neighboring countries in which refugees find themselves are not keen to give up productive land so it may be smothered by the foot traffic of countless foreigners. IDP camps, they are the lesser known places, and IDPs themselves – they are a forgotten people.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP Camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

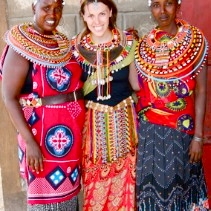

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP Camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

IDPs are different from refugees in one big way: the are citizens of the nation in which they are displaced. They have not crossed any international borders. How have they lost their homes in their own country without swift compensation? Often, it is an internal conflict targeting a specific population, causing mass movement of people – but not quite all the way to country borders – out of their homes and to, well, usually no known destination. The conflict can be ignited by local citizens and it can also come from the government itself, as is the case in Sudan where it is the government that is, among other things, bulldozing inhabited slums on a regular basis. It is internationally agreed that only national governments are responsible for IDPs – the UN High Commissioner for Refugees is intentionally blind to IDPs because they are still technically under the jurisdiction of their own country. But what happens when the government is in fact to blame for the displacement, or at the least is complicit in the unjust movement of its own citizens? This is how the begrudging and eventual forgetting of IDPs begins.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP Camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP Camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

In Kenya, it was not the government itself that incited the movement of thousands, but it was the political ties of certain ethnic groups that led to the eruption of violence. Just hours after the presidential election results were announced on December 30th, 2007, locals took to the streets, selected neighbors homes, then burned, looted, and sometimes killed, those inside. Why: the president who was said to win the election was the incumbent, Mwai Kibaki. Many Kenyans were hoping for the victory of Kibaki’s opponent, Raila Odinga. It was argued by Odinga’s supporters that Kibaki rigged the election. And here is the explosive ingredient: Kibaki is Kikuyu, Odinga is Luo.

Kikuyus and Luos are two of the many tribes in Kenya; almost every Kenyan strongly identifies with their tribe of origin, and the livelihoods associated with that tribe. The Samburu tribe I lived with in June is one of these tribes. The Kikuyu tribe comprises the majority in Kenya. Just as there are specific tribes, there are also certain areas each tribe hails from. If a Kikuyu is found outside of Central Province, for example, he or she is considered to be somewhat of a foreigner, and may even have land taken from them without reprieve (despite having legal ownership) in other provinces that are more strongly associated with other tribes. This deserves an additional note: the first president of independent Kenya – Mr. Kenyatta – was Kikuyu. At the time he came to power, tribes were intermixed in many areas, but there were more distinct boundaries between different tribes’ areas of influence. Kenyatta forcibly moved Kikuyus out of Central Province (encouraging, he said, “ethnic integration”) and settled them in other provinces, inserting his tribal influence in areas that were previously dominated by Luo, Kalenjin, and others. This was over thirty years ago. Kikuyus outside of Central Province today – no matter how long their lives in other parts of Kenya – are seen and often treated as guests who have overstayed their welcome. It should also be noted that I interacted almost entirely with Kikuyus during my visit to the IDP camp, and my perspective has been heavily influenced by the Kikuyu experience. Luos and Kalenjins have a crucial say in this matter – and I regret that I have not collected it to share with you here.

When Kibaki “won” the election, several non-Kikuyu tribes were enraged and saw this as a stolen victory of the entire Kikuyu population. The Luo tribe was targeted, in turn, by the Kikuyus, because of Odinga’s affiliation. The Kalenjins aligned themselves with the Luo, equally furious over Odinga’s loss and collectively, on December 30th 2007, they went to any nearby Kikuyu home or business they knew. Sometimes these Kikuyus were next-door neighbors, or in-laws of the very people who were now storming their houses, taking their chickens, and setting fire to their roofs. The violence continued for days, even months in some places, and the small towns in the western highlands of Kenya were some of the most affected. Kikuyus here were already seen as glorified squatters, and the violence unleashed on them was unmitigated. That is how this IDP camp, initially overflowing with 150 families, began. One of the camp members is the actual owner of the land; she gave it over to the wandering families who had nowhere to go after the night of December 30th.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP Camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP Camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

It took nearly two months for the election controversy to reach a tentative solution. Kibaki was named president and Odinga, prime minister. The two former enemies now share power (although it is widely known Kibaki wields the stick), and the divisions within their government only grow each month. Kenyans are already talking about 2012, when the next election will take place and another rupture in civil society is all but inevitable. Despite the current political compromise, very little action has been taken to resettle those people who lost their homes, family members, and livelihoods. Kibaki doesn’t claim responsibility for the tribal conflict, nor does Odinga – it was not our fault that people took to their roots and sought revenge, both of them reason from their velvet-upholstered chairs and gated communities. With the government’s familiar forgetfulness, the IDPs at Lelmolok have no other “legal” guardians; they have become orphans with parents, without homes, and the sight of someone else’s corn growing all around them.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP Camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP Camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

We have come here to meet the young people at Lelmolok, and here about how Ripe For Harvest’s youth mentoring program has affected their lives. It has been a year now since local university students have been visiting youth at the camp, coming every week to offer guidance, and sometimes just listening, to the kids between 13 and 17 years old. In coming blogs, I will introduce you to the mentors and mentees, and to how important it is that we be present for each other – that we be, I’ll say it, human with each other, and listen.

Posted By Kate Cummings

Posted Jul 24th, 2009