We met Felistus at the orphanage that Saturday, just after the four-hour mass and right before we received two bunnies as party favors. Felistus told Abby she lived in Nakuru – the very town we were to visit the following week – and would be happy to house us. In fact, she was delighted we were coming: the children would be thrilled. Abby introduced this free housing to me before mentioning there was an orphanage attached – with 10 young children. I tentatively agreed in Felistus’ presence, and on the day of our departure for Nakuru it was decided this was the most sensible (well, economical) option. We thought the 10 children would be the challenge; they were, in fact, angels. The devil is in the details.

We are going to get into a topic that you won’t like – how money is funny. More specifically, how a focus on money can narrow even the most generous of people. This story serves as an example of a common and nonetheless vexing money fixation that might as well be a drug habit, because it’s effects are the same on the human brain and internal organs. This sounds overdone, but hold on: come to Kenya, or for that matter take a look around wherever you are, and you might find I’m not exaggerating.

Felistus’s home is about 20 minutes outside of Nakuru town. When we arrived by matatu and then taxi, it was late afternoon and the grounds were peaceful. We entered the main cement house, its windows open and wafting gentle breezes through the corridor. The smooth and recently laid tile beneath our feet was like cool water (one begins to pay attention to textures underfoot when there is enough variation in flooring), and our rooms were complete with mosquito netting and a heated shower next door. Felistus guided us to the dining room, where we laid our arms a bit too heavily on the table and ate several of the fat-fingered bananas. She showed us her side of the house – her ample room with two walk-in closets and a shower almost as big as the room. She gestured to her desk in the corner – complete with large computer and full stereo. “I have internet all day long,” she smiled. The wall decorations were pictures of Felistas with different hair styles, and some posters of Jesus. Felistus was a Catholic nun for 14 years; she left the convent four years ago.

In the house there were also two young women (her nieces) and a man who did the cooking. Felistus walked us outside across the gravel driveway to the adjoining building, one that was taller and made of unfinished cement. As we entered the doorway, I turned to see a neat row of 10 little bodies, all sitting dutifully by the side of Felistus’s house. No one made more than a mouse-sound, but all of them watched us carefully. Felistus noticed that I had noticed them, so she redirected the carefully planned tour to introduce us to the children. Each one of them extended a hand to me, bowing down full bent-knees when I shook their hands. I began to mimic the bent-knee reaction with the handshake, and all of us were bobbing up and down, giggling at learned formality. They returned quickly to their seats, and Felistus promised we would meet them again later. We returned to the unfinished building’s doorway.

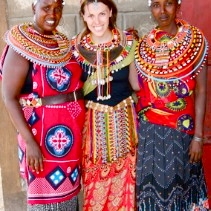

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Nakuru, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Nakuru, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009

The floor was different inside the second building – remember, variations abound – it was in fact, uneven cement. “This building was built not long ago, and we are hoping to get donations for the floor. Right now, we have no money for tile.” We entered the stark hallways of the first floor, the white drywall spattered with stray traces of gray cement. The kitchen and dining room were simple, “the children eat here – do I eat with them? Oh”, laughing, “sometimes I come to visit”, and the bathroom at the end of the hall served as the shower and toilet for all 10 children. “And where do they stay?” We moved upstairs. The stairs, also coarse cement, led us to another bleak hallway. The room by the stairs, set apart from the others, was for the man who looked after the children day and night. There was no similarity between his room and ours. The grey of the cement was the only color, besides some blue and red clothing on the bed. The children’s rooms were brighter, and that was because we knew the children had been there. Their few belongings were neatly laid beside each bunkbed – backpack, shoes, sweater. One of the girls came into the room when we were there, and lithely climbed up to her high bunk, smiling shyly down to us when we persisted in being there. I moved into the next room; Felistus followed me. “You know,” she whispered loudly, “that girl is a total orphan.” “Okay,” I said. I waited to hear what else she may have to say about the child, but she had moved on to another topic. Luna entered the room a few minutes later and Felistus turned to her, and with the same sharp whisper said, “you know, that girl is a total orphan.”

Felistus was most excited to show us the third floor. We walked gingerly up the stairs, some stray hairs of barbed wire jutting out from the cement pillars. From the open-air roof, we could see the surrounding hills of Nakuru – “this is where we hope to build another level for more children one day”, Felistus’s voice was a little softer and her eyes widened with what she imagined. “Someday there could be 200 children here. We want to be able to accommodate that many.” She continued, building the other floors for us, constructing the extensive network of school buildings and the in-house clinic that would exist when these hundreds of children arrive. The building was almost the size of the entire block before she directed her gaze back down, to our eye level, and her tone changed to that of someone who has been abruptly returned to reality.

“All of these things take money, and you know we have very generous donors from Holland. But they have asked us to find more friends – friends who can help us care for all of these needy children.” She kept us on the third floor, going over each aspect of her project that was short of funds, and I listened with awareness and growing uneasiness. For the next three days, Felistus’s intentions grew more apparent. The second night, she turned to Luna at dinner and said, “you know how to make a website?” Luna replied yes. “You make one for me.” It was unclear if this was a demand or a question. The third day, Luna left early for town and I was to follow in the afternoon. Felistus entered my room shortly after nine, and invited herself to sit beside me on my bed. “I noticed you have used your sleeping bag every night, and not the sheets I put on your bed.” I fumbled, saying something about liking my sleeping bag. She raised her eyebrows and held them for a moment, to note her judgment. I was familiar with this look – it was the same one I received when I said I ate vegetables, not meat, and when I said I liked hot water more than milk-tea. These were inappropriate choices, I learned.

Felistus returned quickly – almost imperceptibly – to the facial expression that matched the reason for this visit; it was one of fatigue, and diminished hope. “Kate, you know, it takes so much funds to run this place. You have seen how happy the children are? They are so happy. This is not how they were when they arrived.” She continued, repeating what I have already heard, but with bluntness. And here is what is complicating – I know those children are happier; they are most certainly better off here, more loved here. I have trouble, however, reaching the children through the woman in front of me, who both controls their future and seems to be progressively narrowing possibilities (for everyone) in her pursuit of the ever-elusive but highly sought-after money-pot. The money-pot is the money-drug’s undying hope for salvation. Felistus has (mistakenly) taken me for a money-pot, and I know there is no convincing a person otherwise when the craving has taken over as I feel it has in this room, on this bed.

Felistus informed me it is my duty to bring people here, white people like me who will stay for months at a time and play with the children – and pay for the room, and the food, and the children to have food, and rooms. I told her I would try to inform others of her home. She is disappointed in me; this is not money-pot behavior. After she leaves the room, I have a choice. I can give her some money for the room that I understood was free, hoping it will reach the children. Or, I can let my frustration and my pride make the decision – she will not get any money from me – no, more specifically, her money-drug mind will not get any money from me, the false money-pot.

I walked to her room, my entire middle knotted in defiance. “Felistus?” I called, and she came. “Here is some money, for the children.” Her eyes widened, and she smiled. I returned to my room, where she soon visited me again – “You know, I am very glad you came,” and she resumed her list of expectations and needs.

This is how the money-drug works: I, a student with debt and minimal funds, become – from the money-drug perspective – a white-person-with-money. And Lots of money – so much of it, in fact, and so many connections to more of it, that I must want to give it to others in ample amounts. To Felistus, who chooses to see me as white-person-with-money, I am everything she has dreamed of. This is where the drug of money becomes dangerous. When it is all you look for, it is all you see in others – whether they might have it, or might be craving it. The seeking of money is a false divining rod that can lead a person to a poor student (me) or to a donor who may have money but may not be trustworthy.

[Note: I am oversimplifying, underestimating, and dramatizing – I know. This is a story about a larger story and Felistus is a mirror for us, of all the parts of her that are in us and around us. And, all the parts of us that are in Felistus and around her.]The drug’s consequences continue. Over the course of my three-day stay, I began to notice more about our housing. The children were scuffling over rough cement while we skimmed across fresh tile. Felistus’ room was adorned with more modern electronic equipment than most middle-class Western homes, and her closets were full of new, recently starched outfits. Was there really a lack of funding for the children? Was all this searching for money holy, in the end, if it was all for the sake of these children? I wonder, especially for this former nun, where is God in money?

And this: in a country that has received so much on foreign aid over the past decades, and has come to associate – on a national level – white with funding, how much is this Felistus and how much is this the habit of historical, habitual relationships? I take this precedence of my skin color over my individuality as a personal attack, but just like any drug’s effect or habitual pattern, this is not about me – and Felistus is not alone.

So we are left unfinished, and strangers to each other, in an almost three-story building with 10 children and a former nun surrounded by electronics and large closets. The ways into the heart are fewer with so much between us.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Nakuru, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Nakuru, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009

Posted By Kate Cummings

Posted Jul 23rd, 2009

3 Comments

Stacey

July 23, 2009

Hi Kate:

Our mutual friend, Jeremy, shared your blog site with me. These pictures are lovely, and make me miss Kenya quite a bit.

I used to live in Kenya where I was an Associate Peace Corps Director for Public Health (2005-2006). I worked mostly in Nairobi, but got to travel throughout most of the country.

I think Kenya and Kenyans are beautiful. And I can understand and relate to everything you’ve written here. Our volunteers struggled with this nearly constantly. They (most) had the advantage of working there for 2 years, which could be enough time to establish relationships and to clarify what their roles would be. It was still incredibly challenging.

Raymond Remedios

August 21, 2010

Hello Kate,

I know you wrote this a while back and I am grateful. I recently hooked up with Felistus via Facebook. Her chat request for funds were the first thing that I was approached for. I told her that I need her parish community info to present to my parish community.

Obviously the same thoughts went through my mind as you expressed. My question to her was why was she not associated with any international group? What is the funds going for?

You have brought some clarify to the situation.

Thank you for your frankness and love.

Gold bless