It’s done; my fellowship is over. As a matter of fact, I have already left Lima. I am currently sitting in a coffeeshop in the gorgeous southern city of Arequipa, and tomorrow I will try my luck at ascending the 5,822 meters of the mighty Misti volcano, before moving on to Bolivia for a few weeks of travelling. Nevertheless, over the next few days and weeks I will continue to process the material I have collected during the last very hectic weeks I spent at EPAF.

So, without further ado, the Relatives Unite Part II.

As I mentioned in my previous post, the first part of a week-long meeting of relatives from the Pampas-Qaracha river basin region of Ayacucho took place between October 27th and 30th in Ayacucho’s capital, Huamanga.

After a presentation and warm up activity, the first morning of activities began with a workshop aimed at elaborating a common agenda and a set of common demands that would later be communicated to various authorities. The reasoning behind this was that the scheduled meetings of the next few days would be much more effective if the relatives were able to express clearly and succinctly a set of demands reflecting the common needs and rights of the relatives of victims of enforced disappearance.

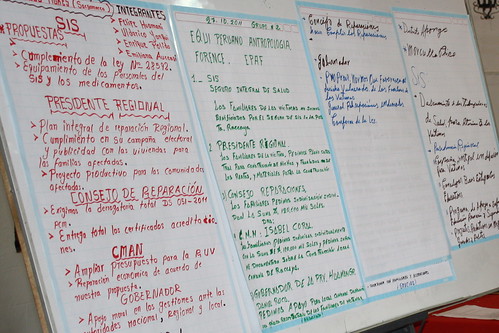

To begin, the representatives were asked to divide into groups representing each community, and write down their demands for each of the relevant entities they would later meet representatives from: the Seguro Integral de Salud (SIS), the Consejo de Reparaciones, the Comisión Multisectorial de Alto Nivel (CMAN), and regional authorities.

During this activity, it was easy to see the difference between those communities where EPAF has been realizing empowerment workshops or communities that have long-standing victims’ associations (Raccaya and Sacsamarca, for instance) and communities where EPAF has only just started working. There was a noticeable difference in the level of information and awareness about what the institutions were, their respective roles and responsibilities, and recent developments affecting the relatives’ right to justice and the truth, such as the Supreme Decree 051-2011 on reparations, about which I have written before (link).

The delegates were then asked to choose one person to present their community’s demands to the rest of the group. While some of the demands were specific to each place; many others reflected common issues and problems, which made the next task of synthesizing the morning’s work into a set of common demands much more manageable. Many of the demands centered on the difficulties of accessing the health benefits they are entitled to as victims and around their opposition to the terms of reparation set out by the Supreme Decree 051-2011, especially with regards to the amount established, time limit, and age requirements.

In the afternoon, the group took a break from this intense activity and made its way to the Universidad Nacional San Cristóbal de Huamanga’s Cultural Center, where the 7th annual Latin American Forensic Anthropology Conference was taking place. As organizer of the event, and given its emphasis on working with and for the relatives of the disappeared, EPAF insisted on including a roundtable on the experiences of the relative at what was an otherwise scientifically-oriented conference.

The roundtable was moderated by EPAF operations director, La Cantuta relative and activist extraordinaire Gisela Ortiz, and included the participation of Alfredo García from Raccaya, Adelina García from ANFASEP, Dionisio Arguedas from Huamanquiquia and Felipe Huamán from Sacsamarca, who all shared their experiences with the substantial crowd of professionals from all over Latin America, students and others.

The roundtable was concluded by an emotional tribute to the relatives during which flowers were distributed among the audience so that each person could personally pass them on to one relative as a symbol of the recognition of their suffering and as a way to apologize on behalf of Peruvian society, which generally stood idle from the safety of its cities while the Ayacuchan countryside was being torn apart and massacred by both sides of the conflict.

On the next day, the ladies from ANFASEP came to visit the relatives. ANFASEP is probably Peru’s oldest victim association, created in 1983 by mothers tirelessly searching for their disappeared son. Their determination is legendary and they are a true symbol of the fight for human rights and the search for justice of the relatives of victims of enforced disappearance in Peru.

The morning turned into a rich and fruitful exchange—conducted entirely in Quechua—between the ladies of ANFASEP and the relatives gathered in Huamanga. For most of the relatives coming from remote villages, it was the first time that they had heard of ANFASEP or were exposed to a victim’s association that had been active for so long. Hearing about ANFASEP’s experience left them captivated and they had many, many questions.

I think an exchange of experience like this one was invaluable for the relatives; more than teaching them about the importance of organization and persistence in the fight against impunity, they also recognized their story in the ladies’ story—fully realizing perhaps for the first time that their communities were not alone in their suffering; that the same horrors had actually happened all over Ayacucho. This sense of solidarity, of shared experience, can—and seemed to—be very empowering for the relatives.

Perhaps the motherly aspect of the “madres de ANFASEP” also helped to create a strong bond with the other relatives. By the end of the meeting, everyone had vowed to keep in touch and collaborate together, and the relatives made sure to invite the ANFASEP ladies to visit their respective villages.

That afternoon, another meeting was held with representative of the CMAN’s office in Lima and Ayacucho (responsible for the elaboration of policies on reparation), CONAVIP-Ayacucho (an umbrella organization of organizations of people affected by Peru’s political violence), the regional government’s human rights office, and a former human rights activist recently elected to the regional government. It was an occasion for the relatives to share their concerns with these regional authorities and bring forth the demands they had jointly discussed and elaborated the previous day. Once again, the meeting was productive; it offered a chance for people who often feel isolated and helpless to express their concerns and demands to the pertinent authorities, and feel like at the very least they were listened to.

The next day was spent with an leadership workshop with REDINFA’s Raúl Calderón in the morning, and a visit in the afternoon to some of Huamanga’s “memory” attractions such as the ANFASEP museum, the “Memory Park,” and a memorial to the journalists killed in Uchurracay in 1983. In the evening, we all packed into a bus for the night-long trip to Lima, where the meetings, workshops and other activities would continue.

This post is already too long so I will limit myself to making a few observations. During the workshop in Huamanga, an aspect that struck me was that men were generally appeared much more informed than women. As a result, the few women that were present did not participate as much as the men did.

Moreover, women from isolated Quechua-speaking villages often cannot not express themselves as fluently in Spanish as the men. While everyone was fully encouraged to speak in their native Quechua and every effort was made to translate the Spanish portions, I still got the sense that there were at times language barrier issues; that they were holding back somehow.

This is something that should be taken into account by any organization working in Peru’s post-conflict communities. There are specific issues affecting women much more than men, such as the widespread use of sexual violence against women during the conflict and the psychological marks this has left, and these are unlikely be given the attention that they should unless women are specifically targeted and attended to.

Also, the meetings made me realize the power and importance for these communities to be organized. News simply do not travel to them the way that we are used to. Developments at the national level highly relevant to their search for truth, justice and reparation can take months to reach them, if they ever do. More and better communication is necessary among communities, and between the communities and the capitals Huamanga and Lima. These communities are so isolated that it is difficult to foresee them realizing major achievements unless they are very organized and put their collective weight down.

Coming soon, The Relatives Unite Part III (in Lima).

Posted By Catherine Binet

Posted Nov 22nd, 2011