The Rio Negro Memorial Textile

Background

The Rio Negro Memorial Textile commemorates those who died in a series of brutal massacres in the Guatemalan province of Alta Verapaz in 1982. The massacres were triggered by a 1978 decision of the Guatemalan government to build a hydroelectric dam, named Chixoy, across the Rio Negro River in Alta Verapaz. This had the effect of flooding a large area and uprooting five local indigenous communities. The project received funding from the international development banks and was harshly criticized by human rights groups.

All but one of the five communities agreed to relocate to other areas. The villagers of the Rio Negro community, however, held out and refused to leave. Like most indigenous communities they viewed their land as sacred and belonging to their ancestors.

The Rio Negro families paid heavily for their beliefs and were subjected to a series of attacks from right-wing militia allied to the Guatemalan military. Many of the militia were from the neighboring village, Xococ. While Xococ also suffered from violence, its inhabitants broadly agreed with relocation and asked the military for permission to form defense patrols. These turned into terrifying instruments of genocide.

The first attacks occurred on February 13 1982 in Oxoc itself. Most of those who survived fled back to the village of Rio Negro or into the foothills to a community called Pak’oxom. When it became clear that more attacks were imminent, the men retreated deeper into the mountains, assuming that they would be the ones to be targeted.

There was to be no reprieve for Rio Negro. The village was flooded along with the rest of the valley and over the next two years survivors trickled back down from the hills to a makeshift resettlement camp at Pacux, set up by the government in the town of Rabinal. Pacux was a dismal place compared to the natural beauty of Rio Negro but it also gave rise to one of the most effective survivor movements in Central America, the Association for the Integral Development of the Victims of Violence in the Verapaces, Maya Achi (ADIVIMA).

In 2000 AP was asked to profile ADIVIMA’s campaign by Rights Action, which supports community activists in Guatemala. We met with Carlos Chen, one of ADIVIMA’s leaders, at a demonstration outside the World Bank and were impressed. Within weeks, Peter Lippman, a founder of AP and a talented writer, left for Guatemala to tell ADIVIMA’s story.

This was Peter’s third assignment for AP. Over the previous two years he had accompanied Muslim refugees back to their homes in Srebrenica and profiled civil society in Kosovo after the war betwen Serbia and Nato. Peter’s stories about Rio Negro can be found here.

Following Peter’s visit AP deployed five Peace Fellows to support ADIVIMA’s advocacy. We launched our program of advocacy quilting in Bosnia in 2007. The following year we asked Peace Fellow Heidi McKinnon, an accomplished museum curator with a passion for preserving cultural tradition, to see whether there was interest at ADIVIMA in described the Rio Negro tragedy through embroidery.

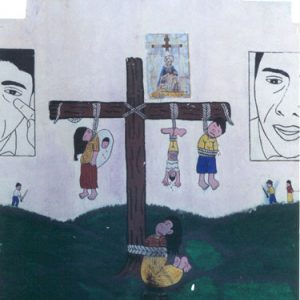

Heidi found fifteen women who had lived through the horror of the March 13, 1982 massacre and had been searching for a way to tell their story through textile. Several were skilled stitchers and made the traditional indigenous tunics known as huilpils.

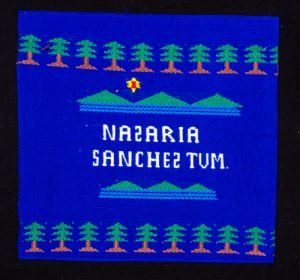

The ADIVIMA artists used the same approach employed at Srebrenica in Bosnia the previous year. Each block carries the name of a single victim, selected by the artist from multiple family members who were murdered.

In the years that followed Heidi’s fellowship, the Rio Negro Memorial Textile itself helped ADIVIMA to advance its agenda for transitional justice in Guatemala. The Textile was first shown internationally in 2012 at the United Nations. The UN arranged for one of the artists, Carmen Sanchez Chen, to fly from Guatemala and attend the exhibition. Carmen introduced the Textile and spoke movingly about the Rio Negro tragedy, with Heidi translating.

As for the broader challenge of securing justice and reparations for the survivors, ADIVIMA’s advocacy turned Rio Negro into something of a test case. The mass graves of the Rio Negro massacre were exhumed. Nine of the killers from Oxoc were prosecuted and convicted.

In 1996, Jesus Tecu Osorio, one of the three founders of ADIVIMA, won the Reebok Human Rights Award. In a momentous decision, the former Guatemelan president Efrain Rios Mott, who presided over the worst killing in 1982, was convicted of genocide in 2013. The judgement was reversed but Rios Montt was retried in 2017 and passed away two years later.

Overall, history will likely judge Guatemala as a modest success for transitional justice. ADIVIMA played a leading role. Photos and profiles by Heidi McKinnon. (October 2020).

Artists

Maria Rosalina Piox Cortez was born near Pacux to survivors of the Río Negro massacres. Maria and her husband, Estuardo Chen Sanchez, have one daughter, Astrid Marisol, and live with Carmen Sanchez Chen’s extended family in Pacux. Maria works at home weaving traditional belts and helps with the local tomato harvests when there is work. Maria wove two panels for the Rio Negro quilt. The first commemorates her husband’s grandmother Narcisa. The panel includes a sun figure and a cross on the mountain to mark the time and place where Narcisa died. It also includes a traditional border design from the region. Maria wove her second panel in memory of her grandfather, Don Guillermo Sanchez, 55. Maria is a member of the Pacux artisans’ cooperative.

Maria Rosalina Piox Cortez was born near Pacux to survivors of the Río Negro massacres. Maria and her husband, Estuardo Chen Sanchez, have one daughter, Astrid Marisol, and live with Carmen Sanchez Chen’s extended family in Pacux. Maria works at home weaving traditional belts and helps with the local tomato harvests when there is work. Maria wove two panels for the Rio Negro quilt. The first commemorates her husband’s grandmother Narcisa. The panel includes a sun figure and a cross on the mountain to mark the time and place where Narcisa died. It also includes a traditional border design from the region. Maria wove her second panel in memory of her grandfather, Don Guillermo Sanchez, 55. Maria is a member of the Pacux artisans’ cooperative.

Analicia Ixpata was born in Pacux to survivors of the March 13, 1982 massacres. She sees the massacres as part of her family’s history and feels their impact on her own life and that of her husband.Her first panel commemorates Dominga Chen, the grandmother of her husband. Her husband’s father, Fernando Chen Tecu, is commemorated in Analicia’s second panel.

Analicia Ixpata was born in Pacux to survivors of the March 13, 1982 massacres. She sees the massacres as part of her family’s history and feels their impact on her own life and that of her husband.Her first panel commemorates Dominga Chen, the grandmother of her husband. Her husband’s father, Fernando Chen Tecu, is commemorated in Analicia’s second panel.

Laura Tecu Osorio was in Rio Negro on March 13, 1982 when the massacre occurred but was spared because she had just given birth. Laura’s panel commemorates her brother, Jaime. Laura’s other brother Jesus also survived and has been an advocate for the Río Negro community ever since.

Laura Tecu Osorio was in Rio Negro on March 13, 1982 when the massacre occurred but was spared because she had just given birth. Laura’s panel commemorates her brother, Jaime. Laura’s other brother Jesus also survived and has been an advocate for the Río Negro community ever since.

Like all survivors from the Río Negro massacres, Carmen Sanchez Chen suffered a debilitating series of losses. On Februrary 13, 1982 her father, sister and cousin were tortured and brutally killed in the massacres that occurred in the village of Xococ. On March 13, 1982, her mother, two sisters and several cousins were murdered at Pak’oxom, a site above her former home in Río Negro while Carmen was buying sugar in a nearby village shop. On May 14, 1982, Carmen was washing clothes in the Salama River with her three year-old son, Manuel Chen Sanchez, and his grandmother. Manuel was kidnapped by helicopter from the settlement of Los Encuentros and has never been found. Carmen was forced to flee in nothing but her underwear into the mountains, where she lived with her husband for over a year before moving to the resettlement village of Pacux in 1983.

Like all survivors from the Río Negro massacres, Carmen Sanchez Chen suffered a debilitating series of losses. On Februrary 13, 1982 her father, sister and cousin were tortured and brutally killed in the massacres that occurred in the village of Xococ. On March 13, 1982, her mother, two sisters and several cousins were murdered at Pak’oxom, a site above her former home in Río Negro while Carmen was buying sugar in a nearby village shop. On May 14, 1982, Carmen was washing clothes in the Salama River with her three year-old son, Manuel Chen Sanchez, and his grandmother. Manuel was kidnapped by helicopter from the settlement of Los Encuentros and has never been found. Carmen was forced to flee in nothing but her underwear into the mountains, where she lived with her husband for over a year before moving to the resettlement village of Pacux in 1983.

Maria Chen Sanchez was born in the mountains outside Río Negro in 1982. Her mother, Carmen Sanchez Chen, was six months pregnant with Maria when she fled from the Los Encuentros massacre. Maria’s panel commemorates her aunt Dominga, who died at Pak’oxom.

Maria Chen Sanchez was born in the mountains outside Río Negro in 1982. Her mother, Carmen Sanchez Chen, was six months pregnant with Maria when she fled from the Los Encuentros massacre. Maria’s panel commemorates her aunt Dominga, who died at Pak’oxom.

Juana Osorio Sanchez was six when the Guatemalan Army entered Río Negro on March 13, 1982. Her mother, Nasaria Sanchez, left her in the school room with a dozen other children and an eldery woman, Dona Nela, before being marched up the hill to Pak’oxom by PAC members. An hour later shots were heard. Doña Nela took all the children from the school and ran into the mountains where they lived for eight days without food or water. Juana eventually reacher the nearby settlement of Los Encuentros where she was cared for by her aunt Carmen Sanchez Chen. Nasaria and Juana’s sister Luisa Osorio Sanchez were killed at Pak’oxom that day. Two months later, on May 14, 1982, Juana was at the river playing with her friends when violence began again. Juana fled into the woods naked with the other children, where they stayed for five days. The brother of one of the children found them and Juana was later taken to an orphanage in a nearby state run by the Sisters of Charity. She stayed there for a year until her father found her and she moved to Pacux. Juana is now married to one of those children who hid in the mountains with her on May 14, 1982. They have four children. Juana teaches basic Maya Achí literacy to adults in her home in Pacux through a state-funded program called CONALFA. She weaves belts and huipils in her spare time and is the secretary of the Pacux artisans’ cooperative.

Juana Osorio Sanchez was six when the Guatemalan Army entered Río Negro on March 13, 1982. Her mother, Nasaria Sanchez, left her in the school room with a dozen other children and an eldery woman, Dona Nela, before being marched up the hill to Pak’oxom by PAC members. An hour later shots were heard. Doña Nela took all the children from the school and ran into the mountains where they lived for eight days without food or water. Juana eventually reacher the nearby settlement of Los Encuentros where she was cared for by her aunt Carmen Sanchez Chen. Nasaria and Juana’s sister Luisa Osorio Sanchez were killed at Pak’oxom that day. Two months later, on May 14, 1982, Juana was at the river playing with her friends when violence began again. Juana fled into the woods naked with the other children, where they stayed for five days. The brother of one of the children found them and Juana was later taken to an orphanage in a nearby state run by the Sisters of Charity. She stayed there for a year until her father found her and she moved to Pacux. Juana is now married to one of those children who hid in the mountains with her on May 14, 1982. They have four children. Juana teaches basic Maya Achí literacy to adults in her home in Pacux through a state-funded program called CONALFA. She weaves belts and huipils in her spare time and is the secretary of the Pacux artisans’ cooperative.

Erlinda Alvarado was seven when her father, Francisco Alvarado Chen, 45, died in the village of Xococ. Francisco left seven children behind. Erlinda’s panel is unlike the others, because it includes an image of the Chixoy Dam, based on Erlinda’s memories of her last visit to the village.

Erlinda Alvarado was seven when her father, Francisco Alvarado Chen, 45, died in the village of Xococ. Francisco left seven children behind. Erlinda’s panel is unlike the others, because it includes an image of the Chixoy Dam, based on Erlinda’s memories of her last visit to the village.

Dominga Grave was born in the mountains outside the village of Joyaba, Quiché in 1982. Her panel commemorates her husband’s grandfather, Victor Lajuj Chen, who was fifty when he died by lasso and machete on February 13, 1982. Dominga designed a scene with mountains and birds.

Dominga Grave was born in the mountains outside the village of Joyaba, Quiché in 1982. Her panel commemorates her husband’s grandfather, Victor Lajuj Chen, who was fifty when he died by lasso and machete on February 13, 1982. Dominga designed a scene with mountains and birds.

Araceli Cical Lajuj has been a weaver since she was 12. Her panel commemorates her husband’s grandmother, Isabel Osorio, who died at Pak’oxom. The panel shows the mountains, pine trees and birds, as a gift to the great-grandmother her three children will never know.

Araceli Cical Lajuj has been a weaver since she was 12. Her panel commemorates her husband’s grandmother, Isabel Osorio, who died at Pak’oxom. The panel shows the mountains, pine trees and birds, as a gift to the great-grandmother her three children will never know.

Isabel Osorio Chen was eleven when her grandmother Juliana Chen,50, died at Pak’oxom with several cousins, aunts and six of Isabel’s seven brothers and sisters. Juliana was a midwife and spiritual leader. Isabel’s panel shows the small mountain lions that roamed Pak’oxom after the massacres.

Isabel Osorio Chen was eleven when her grandmother Juliana Chen,50, died at Pak’oxom with several cousins, aunts and six of Isabel’s seven brothers and sisters. Juliana was a midwife and spiritual leader. Isabel’s panel shows the small mountain lions that roamed Pak’oxom after the massacres.

Ermelinda Uscap Lopez, 24, was born in the mountains outside the village of Chitucan in 1983. Her mother fled Chitucan after an Army raid in the village. After Ermelinda was born in hiding during in the mountains, the family traveled to Pacux in 1984, and returned to Chitucan when they could. As a young girl, Ermelinda learned how to weave belts and huipils and worked picking melons and coffee to make a living. While in the fields, she met her husband, José Osorio Osorio, and then moved to Pacux. Ermelinda’s textile panel commemorates her mother-in-law, Maria del Rosario Osorio Chen, who left her fire burning and her tortilla masa unfinished the morning she was killed at Pak’oxom. Maria’s husband, José, was one of the children taken to Pak’oxom. He witnessed his mother’s death and was held in slavery in the nearby village of Xococ for two years following the massacre. Ermelinda and José have three children. She weaves belts to order and is a member of the Pacux artisan’s cooperative.

Ermelinda Uscap Lopez, 24, was born in the mountains outside the village of Chitucan in 1983. Her mother fled Chitucan after an Army raid in the village. After Ermelinda was born in hiding during in the mountains, the family traveled to Pacux in 1984, and returned to Chitucan when they could. As a young girl, Ermelinda learned how to weave belts and huipils and worked picking melons and coffee to make a living. While in the fields, she met her husband, José Osorio Osorio, and then moved to Pacux. Ermelinda’s textile panel commemorates her mother-in-law, Maria del Rosario Osorio Chen, who left her fire burning and her tortilla masa unfinished the morning she was killed at Pak’oxom. Maria’s husband, José, was one of the children taken to Pak’oxom. He witnessed his mother’s death and was held in slavery in the nearby village of Xococ for two years following the massacre. Ermelinda and José have three children. She weaves belts to order and is a member of the Pacux artisan’s cooperative.

Florinda Canahui Coloch wove a textile panel for her husband’s aunt, Juana Tecu Osorio, who died at Pak’oxom with her two children and three siblings. Juana was only eighteen at the time of her death. Her younger brother, Jesus, was enslaved at Pak’oxom by PAC militia from the nearby village of Xococ.

Florinda Canahui Coloch wove a textile panel for her husband’s aunt, Juana Tecu Osorio, who died at Pak’oxom with her two children and three siblings. Juana was only eighteen at the time of her death. Her younger brother, Jesus, was enslaved at Pak’oxom by PAC militia from the nearby village of Xococ.

Josefa Ixpata Chen was born and raised in La Laguna near the village of Chisacap in Alta Verapaz. She was seven years old when her village was burned and her family fled to the mountains in 1981. The family then went to live in Rio Negro, but her father went into hiding in the mountains as word spread that an attack was imminent. Josefa recalls: “We then relived everything that had happened before.” After Josefa fled from Río Negro, the family resettled to a house with other relatives in San Cristobal, Alta Verapaz. But the relatives did not welcome them and they lived in a bamboo shack without food or water and were treated like guerrilleros. Josefa left for Pacux with her uncle in 1984. Her parents arrived separately in Pacux later that year. Since 1984, Josefa has become increasingly active in her community. She began to weave when she was nearly twelve and has been making huipils and belts ever since. Josefa is currently a health promoter in Pacux and in charge of five health workers and one midwife. She receives training through a government program every two weeks and then gives capacity-building workshops to her staff. As part of job, she is in charge of vaccination campaigns and conducts an annual census in Pacux. Josefa also updates the community maps every few months to follow people as they are born, marry, migrate, move or die. Josefa wove two textile panels in memory of her great grandparents, her husband’s twenty-one year-old sister, Narcisa, and his six year-old sister, Juana. Narcisa and Juana were tortured and strangled in Pak’oxom and Los Encuentros.

Josefa Ixpata Chen was born and raised in La Laguna near the village of Chisacap in Alta Verapaz. She was seven years old when her village was burned and her family fled to the mountains in 1981. The family then went to live in Rio Negro, but her father went into hiding in the mountains as word spread that an attack was imminent. Josefa recalls: “We then relived everything that had happened before.” After Josefa fled from Río Negro, the family resettled to a house with other relatives in San Cristobal, Alta Verapaz. But the relatives did not welcome them and they lived in a bamboo shack without food or water and were treated like guerrilleros. Josefa left for Pacux with her uncle in 1984. Her parents arrived separately in Pacux later that year. Since 1984, Josefa has become increasingly active in her community. She began to weave when she was nearly twelve and has been making huipils and belts ever since. Josefa is currently a health promoter in Pacux and in charge of five health workers and one midwife. She receives training through a government program every two weeks and then gives capacity-building workshops to her staff. As part of job, she is in charge of vaccination campaigns and conducts an annual census in Pacux. Josefa also updates the community maps every few months to follow people as they are born, marry, migrate, move or die. Josefa wove two textile panels in memory of her great grandparents, her husband’s twenty-one year-old sister, Narcisa, and his six year-old sister, Juana. Narcisa and Juana were tortured and strangled in Pak’oxom and Los Encuentros.

Martina Osorio experienced unimaginable trauma in her early life. She was one of 13 children. Three died of disease and 6 were killed. Today, Martina gives classes on hygiene and education to mothers. She wove her panel for her father, Lorenzo Osorio, who died in Xococ.

Martina Osorio experienced unimaginable trauma in her early life. She was one of 13 children. Three died of disease and 6 were killed. Today, Martina gives classes on hygiene and education to mothers. She wove her panel for her father, Lorenzo Osorio, who died in Xococ.

Fermina Gabriel Castro was born in Hoyaba in the state of Quiche, where she lived until 1981 when her village was raided by the Guatemalan Army and PAC patrols. In one year, over 100 people from her village were killed, including her mother, husband, and brother. Following the act of violence that led to the deaths of over fifty people in one day, Fermina fled into to the mountains wit her first child and a second on the way. Like many other displaced people at the time, she lived alone in the mountains, afraid of anyone else she encountered. Fermina survived on avocados as her sole source of nutrition and after eight months of living without shelter, she gave birth alone to a little girl in 1982, Dominga, who was named after her mother. After two years in the woods, Fermina moved to Pacux, where she worked at the military post washing clothes. Her work since, both in Quiche and in Pacux, has been as a comadrona, or midwife for the community. Over the past 35 years, Fermina has assisted with the births of over 10,000 babies.

Fermina Gabriel Castro was born in Hoyaba in the state of Quiche, where she lived until 1981 when her village was raided by the Guatemalan Army and PAC patrols. In one year, over 100 people from her village were killed, including her mother, husband, and brother. Following the act of violence that led to the deaths of over fifty people in one day, Fermina fled into to the mountains wit her first child and a second on the way. Like many other displaced people at the time, she lived alone in the mountains, afraid of anyone else she encountered. Fermina survived on avocados as her sole source of nutrition and after eight months of living without shelter, she gave birth alone to a little girl in 1982, Dominga, who was named after her mother. After two years in the woods, Fermina moved to Pacux, where she worked at the military post washing clothes. Her work since, both in Quiche and in Pacux, has been as a comadrona, or midwife for the community. Over the past 35 years, Fermina has assisted with the births of over 10,000 babies.