Challenge

Visit the Profiles tab to meet the individuals cited on this page

At the heart of conflict: Herders from the Turkana and Samburu tribes fight over cows in northwest Kenya.

Baragoi sub-county has been the scene of conflict between Turkana and Samburu for generations, although the current violence began in earnest in 1996. The conflict takes the form of intermittent raids by bands of armed men, known as warriors. Their goal is to steal livestock – cattle, camels and goats – or to avenge such thefts. But raids can turn deadly and embroil whole communities. Esther Lenosilale (Samburu) lost three uncles during the war between the Pokot and Samburu and told an AP team in 2017 how she had made her children wear shoes to sleep in case they had to flee suddenly: “When the sun came up I thanked God I was still alive.“ Samuel Lemaramwit (Samburu), head of the council of Elders in Longewan village, reckons that 35 of the village‘s inhabitants (who currently number 412) were killed by Pokot warriors before the fighting finally stopped.

The same was true of the Pokot side. Evelyn Mung’a, the deputy principal at the Plesian School, remembers how Samburu raiders descended on her village: “Around 5 in the morning, I heard gunshots and came out of my house. There was a Pokot homestead surrounded by Samburus. They killed 10 people including children. An injured 2 year-old came to our school and later died. It was so painful, that day still wrings my mind.”

The Impact – Communities Under Siege

The impact of such inter-communal conflict is devastating. During the Pokot-Samburu war, schools were closed and students were drafted into the local defense force. When Esther Lenosilale’s son Caleb returned to school at the age of 20 after the Samburu-Pokot fighting ended, he had missed so many years of school that he was placed in the first grade with students aged 13. CPIK estimates families were able to harvest around 2 bags of corn during the war, compared to the normal yield of over 40 bags. The cattle economy collapsed.

Caught in the crossfire: Women and children, like these Turkana girls, are the first to suffer when cattle raiders fight.

The conflict in Baragoi has produced a disastrous separation between Turkana and Samburu. Before the violence began in 1996 both groups cultivated the fertile Namalia belt and produced food together, but today the belt is a no-go zone. Villages have been emptied, people have been displaced, and schools have been closed – some of them permanently.

The two communities do not share resources. Grazing fields and water sources are contested. (There is more water on the Turkana side of Baragoi and better grazing land on the Samburu side, but this incites competition rather than cooperation.) Before the conflict, Turkana and Samburu used to trade livestock but this has stopped. There are no common markets in Baragoi, even though land has been marked out for such a purpose.

The one community where Turkana and Samburu meet is Baragoi Town, which has the only truly integrated school in the sub-county. But even Baragoi Town is divided into two distinct tribal territories by the main road, and most businesses along the road are owned by outsiders (Somalis and Kikuyu). Until 1996, the two communities used a common cemetery but today they use separate burial grounds. Even the dead are not at peace.

Outside Baragoi Town the separation is complete. Salu Lekarere, the principal teacher at Ngilai School, one of the six communities, says his students describe Samburu kids as “the enemy” in their school papers. Not surprisingly, Samburu teachers are afraid to teach at his school.

Root Causes – Warriors, Cows and Drought

Victim of drought: Pastoralist herds have been devastated by three years of drought which forces herders to move outside their own land, provoking conflict.

The authors of this mayhem are young men who are encouraged by a warrior culture which views fighters as heroes. Many grow up hating the other side and their first raid is often a rite of passage into adulthood. Samuel Lemaramwit from the Longewan council of Elders reels off the names of several Samburu fighters who achieved fame during the Samburu-Pokot war – “Lemarimpe, Lerana, Lengapiani.” The same mentality persists across Baragoi.

The root cause of these conflicts is competition for cattle, water and land. Cattle are the main form of wealth and the pastoralists have by tradition followed the rain in search of the best pasture. But this has been made more difficult by drought, which forces the herds to move into the land of other tribes. George Gamiya, a former Samburu warrior turned policeman, explained that he had lost 4 of his 5 cows to drought and disease. Kip Kyeng, a Pokot herder, told AP in November 2018 that no fewer than 14 of his 16 cows had died. Such losses put pressure on herders to resume rustling. They are also boxed in by a government policy of allocating large tracts of land to conservationists which are made off-limits to pastoralists.

To these problems must be added bad management of livestock, and an unwillingness to innovate. Cattle herds are too large for the fragile environment and breeds are inefficient. Eating habits do not help. Chicken is not even consumed by the Turkana, even though chickens would do less damage than cows and be a good investment for women.

The conflict is compounded by deep distrust between the tribes and the government. The Catholic Church administered most of Samburu County following independence, and government came late to Baragoi sub-county. Unable to quell the violence, the authorities chose to arm local militia (known as the Kenya police reserve) but this simply makes guns more available. Instead of working patiently with the communities to end raiding, the police confiscate animals by force from communities that they suspect of complicity, further poisoning relations. The Turkana also feel grievance at the fact that they only have one seat out of 6 on the Baragoi Council.

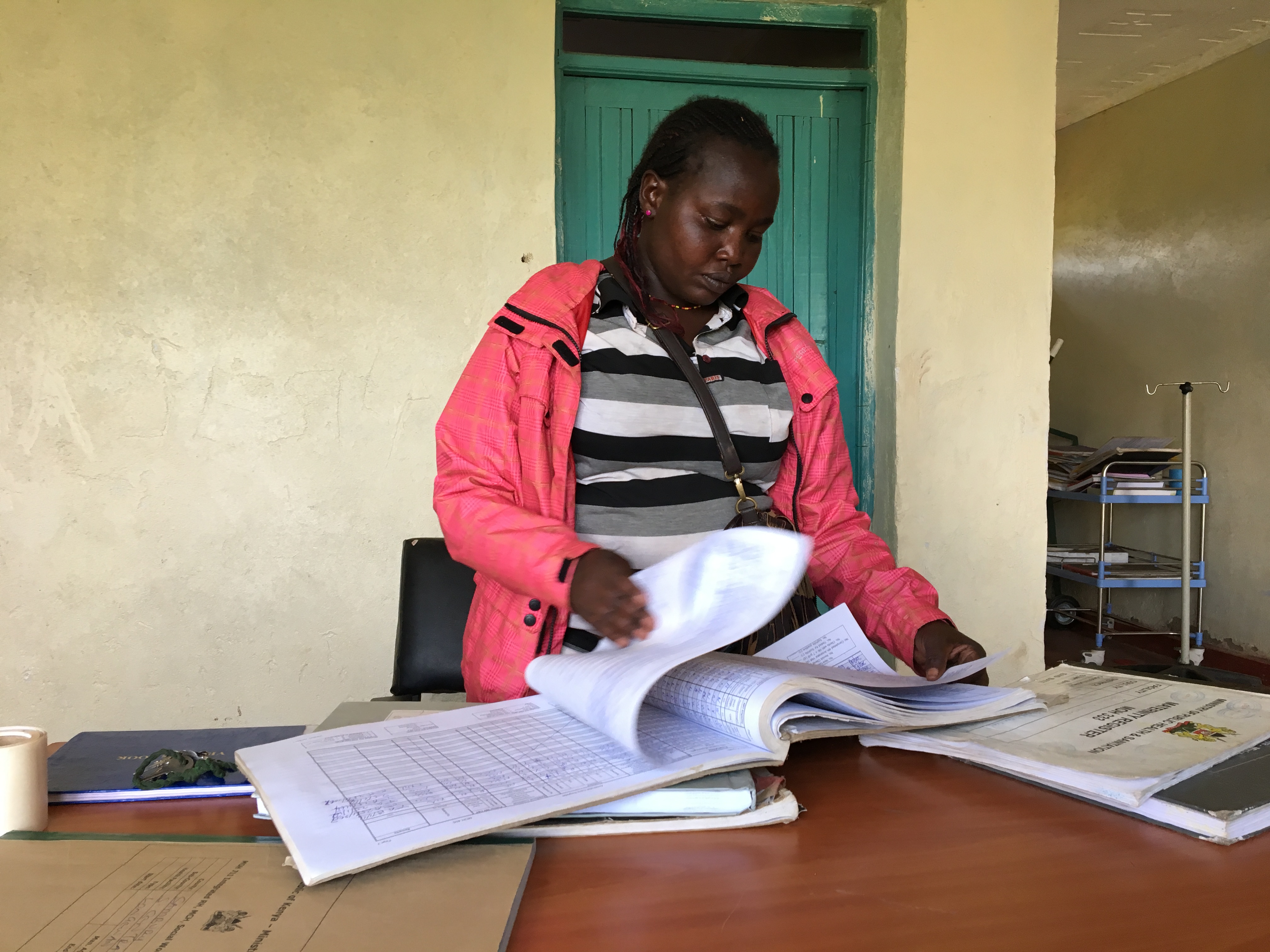

Willing partner: CPIK will draw on a close relationship with the County government to tackle conflict in Baragoi sub-county.

A final feature of the Baragoi conflict is an almost complete absence of NGOs. Salu Lekarere, principal of the the Ngilai School, remembers when his school boasted many partners, including UNICEF and international NGOs. Today, only the Ministry of Education remains. “Most NGOs view Baragoi as a no-go zone,” says Hilary Bukono from CPIK.

Awaiting Innovative Solutions

These are formidable obstacles, but peace-makers have several things going for them. First, the central actors in this conflict are easy to identify, accessible, and can be influenced – which is not the case in most other modern conflicts. Second, Elders (family heads) wield great authority and are also fathers. Third, the government can encourage inter-ethnic cooperation through the judicious appointment of teachers and police, joint services, and by issuing licenses for initiatives like markets.

All of this opens the way for innovative peace-building. The question is whether a small NGO like CPIK can trigger the change. To answer this we turn to the now-resolved conflict between the Pokot and Turkana. The government and Catholic Church tried for years to end the conflict and even employed workers from both sides to work together and dig a road that would benefit the two communities. None of it worked and fighting flared up again in 2008.

Four years later the war began to wind down, and there have been no deaths in the years since. How was this achieved? Could it also happen in Baragoi?

![]()

The Community Response

Visit the Profiles tab to meet the individuals cited on this page

On the frontlines for peace: 276 children from the Pokot and Samburu tribes came together at this Peace Camp, organized by CPIK in July 2017.

CPIK will address the conflict in Baragoi by employing the same tools that worked between the Pokot and Samburu. AP enjoyed a ringside view of this highly successful example of peace-building between 2015 and 2018, through Peace Fellows and staff visits

Frontline villages: The startup will work in six villages in Baragoi which lie along the fault line of the conflict and have born the brunt of the violence. These are Nachola, Natiti and Nalinga Ngor (Turkana); and Ngilai, Bendera and Baragoi Town (Samburu). Frontline villages are key to a larger solution because their inhabitants have the most direct interest in ending conflict and can influence raiders from the interior who pass through their villages. If the conflict can be halted here, it could have a calming influence on the entire region.

Schools: The next step is to contact schools and work with teachers to identify children who will participate in peace camps. Once they sign on teachers will likely remain intensely loyal to CPIK and organize future camps. David Lekirenyei, the deputy principal at Logorate School in Samburu territory, has been committed from the start. He can remember when bullets came whistling through the classrooms and the school had to be closed for two years. Today, Pokot herders pass by the school without incident and the school has two Pokot students. This is a long way from integration but at least the school is functioning normally.

Children: The next stage of the process is to organize peace camps for children from both sides of the conflict. Schools are asked to identify children from grades 5 and 6 who are performing well and are old enough to form friendships. The camps themselves are great ice-breakers, as Peace Fellow Colleen Denny found when she attended a camp in July 2018: “We played sports, we sang songs, (and) we had silly interactions.“ One teacher told Colleen that she had received over 40 calls from parents over the first two days asking if their kids were OK until word got out that they were all fine and that a major change was under way.

Chebet (Samburu) and Helen (Pokot) became fast friends before the peace 2018 camp even began. By the end of the camp they had been officially “twinned” by CPIK. The two Pokot girls at Logorate School referred to earlier, Faith (15) and Mary (13), now spend their holidays with Samburu families. Naanyu and Diana, two Pokot girls, decided to go to a Samburu boarding school to “get away from their families.” It seemed to be working out when we met them in 2017. Anne (Samburu) trekked across a mountain in November 2018 to attend a ceremony with her Pokot friend Naomi, during which CPIK distributed cows in the Pokot village of Plesian. Such cases are legion – and heart-warming. They also show how children can start the ball rolling and become catalysts for peace – one of CPIK’s most important conclusions.

Peace camps also give CPIK the chance to enrich and expand the program. Twelve schools have established children clubs, which are led by motivated students like Tanapa, 16. CPIK’s peace curriculum is now used at 36 schools. The organization is even using the curriculum to train teachers in the Nairobi slums.

Families and parents: The ripple effect from a peace camp spreads quickly to parents who develop their own friendships and follow up by visiting each other’s homes. Mothers are particularly receptive to the call for peace and account for over 75% of the home-stays.

Esther Lenosilale, who is also known as “Mama Caleb“ from the Samburu village of Logorate was one of the pioneers. After her Caleb’s new Pokot friends came to stay at the family kraal, she issued an invitation to the Pokot mothers and sent them home with gifts. When 40 unfamiliar goats wandered into the village in 2017, she contacted her Pokot friends, found out that the goats belonged to the Pokot and sent them back. On the other side Joseph Lomnia (Pokot) hosted several Samburu parents after his son attended a peace camp on the other side. One of his house guests, Peter Lemoti, later joined Joseph to raise a cow under CPIK’s program Heifers for Peace.

The deciders: Samuel Lemanarwit, center, heads the Council of Elders in Longewon village (Samburu). Elders play a key role in ending the warrior culture.

Village Elders: Elders exercise a huge influence on both sides of Pokot-Samburu divide, and led the efforts to end the war. One reason is simply that they are parents, which makes them receptive to CPIK’s approach. Samuel Lemaramwit (Samburu), who heads the village Council of Elders in Longewan village, lost a son in 8th grade during the war and said that the experience turned him into an advocate for peace. Elders used to bless warriors before they set out on a raid, he explained. But after their children started to attend peace camps, the Elders began to denounce the warriors. They never needed to issue a curse – the ultimate reprimand – but their disapproval was unmistakable and the raiding began to slow. Samuel has since visited his former enemies and hosted them at his home in Longewan. He has also helped to find and return animals that were stolen from the Pokot.

Transforming the Warrior Culture

The story of how warriors turned their backs on fighting is dramatic. As with the Elders, many warriors are fathers and they were also impressed when their children began consorting with the enemy at peace camps. Warriors also began to feel the pressure from progressive Elders like Samuel from Longewan. As the community‘s admiration turned to disapproval, the warriors began to lay down their guns.

Some Pokot did not appreciate the transformation. Kanye Kera (Pokot) was a fierce warrior in Amaya village until his son attended a peace camp. He then began to reach out to his former enemies, and when Pokot raiders from the interior came through the village and returned with stolen Samburu animals Kanye confronted them and retrieved the animals. On one occasion he even staged an ambush against Pokot to retake stolen Samburu cows and was accused bitterly by the bandits of betraying his own tribe: “Now you are not our brother. You are not Pokot. You are Samburu,” they told him.

As the former warriors have lost their aura of menace, it has become safer for families from the other side to cross the tribal line. Chepranyei left her parents and home on the Pokot side with her baby after the rains failed and moved onto Samburu land. She lives next to Losieku Lekisima, a former Samburu warrior who even helped to build her house. Losieku has also helped to locate and return stolen animals from the Pokot side.

“It’s all about perception“ says Hilary Bukuno, from CPIK. “Pressure from families and elders has led the fighters to stop raiding and turn to peaceful pursuits. As this happened, public opinion has also changed and come to view the warriors as criminals rather than heroes.“

From heroes to bandits: The end of conflict, and the drought, has put pressure on former Samburu and Pokot warriors.

For many former warriors, the transformation has not been easy. Frances Changulu, 27 (Pokot) gave up raiding and joined CPIK’s program in 2012. Two years later he dropped out of school because he could not afford the tuition. When AP met him in 2017 he was unemployed and had lost 24 of his 27 cows to drought. But this had not stopped him from returning five stolen Pokot cows to the other side – an act, he said, which had made him feel “more like a warrior than ever.“ In spite of being unemployed, Frances said that a return to fighting was unthinkable but he is also under pressure to make ends meet, particularly as food is more scarce and expensive than on the Samburu side. Many former warriors have turned to selling charcoal, which is bad for the environment and actively discouraged by CPIK and Elders.

Enjoying the Peace Dividend

As the threat of violence has receded, cooperation between Pokot and Samburu has deepened, making a resumption of fighting increasingly unlikely. It also makes sense because of disparities between the Pokot and Samburu communities. Amaya (Pokot) is the poorer of the two and also more susceptible to drought. We met one young mother, Lorot Chaptoyia, who had carried her baby for three hours from Amaya to buy maize and sugar in Longewan, where food is cheaper.

Government services are also better on the Samburu side. Since the fighting stopped, a growing number of Pokot women have been visiting the Longewan maternity clinic. Simaloi Dorcas, the nurse at the clinic, said that almost a third of the 362 women who visited the clinic during the first six months of 2017 had been Pokot. Equally striking, 80% of the protein bars given out by the clinic to supplement the nutrition of pregnant women and nursing mothers had been given to Pokot. This showed not just that Pokot women were more in need, but that they felt confident enough to seek support among their former enemies. Such joint use of government services would have been impossible during the war.

The disparity between the two sides can even create comparative advantages. Longewan (Samburu) is at a higher altitude and attracts rainfall earlier than Amaya (Pokot) which means that the maize ripens sooner. High on the plains of Longewan we met Namuk Losangeri and his son, Arrupe Namuk, two Pokot who were harvesting maize for Samuel Lemaramwit (Samburu) for 700 shillings ($7) a day. When the harvest ended, they planned to return to their own land in Amaya and prepare for their own harvest.

Trade between the two tribes has been brisk since 2012, when markets began to re-open after the war. Five markets now operate, with the Pokot markets held on Tuesday and the Samburu markets a day later. Peace Fellow Colleen Denny visited one market and noticed young men from the two tribes eating chapatis together. She noted in her blog: “Eight years ago those same men I saw today would have killed each other on the spot if they saw one another.“

Women of influence: Josephine Lengepyani, a Samburu, has built a business by trading with Pokot and is breaking down gender barriers.

No-one exemplifies the growing inter-dependency between Pokot and Samburu like Josephine Lengepyani (Samburu), one of Longewan’s leading entrepreneurs and an early participant in CPI’s program. Josephine takes orders on her phone from Pokot farmers who send her their maize to be ground. They then come by the village to pay her and pick up their maize when they are visiting the Langewon market. As a prominent businesswoman Josephine is listened to with great respect by the Langewon Council of Elders, which is comprised of men. She is proud to be promoting gender equality in a patriarchal society and says that it “it all began with a peace camp.”

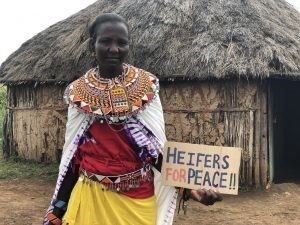

Heifers for Peace

CPIK provides a further incentive to cooperate by giving a cow to families from the two sides on the condition that they rear the animal together. Each cow can be expected to produce milk (which sells for 200 shillings – $2 – a week) and give birth to up to 8 calves. This means that both families have a strong interest in making sure that the animal thrives, which tends to resolve any disagreement over which family should care for the cow. After Malatu Lebenayo (Samburu) and Losuke Lonyangaking (Pokot) received a cow from CPIK in 2015 they decided that Malatu should take the cow because he has access to better pasture land. George Gamiya (Samburu) and Christine Chepteiya (Pokot) came to a similar conclusion. It meant that George would be able to sell milk during the early years, but it would be worth the wait for Christine.

At 20,000 shillings a cow, Heifers for Peace is not cheap and for the last two years CPIK has relied on Peace Fellows Talley and Colleen to raise the money (over $10,000). But the investment has paid off and benefited communities as well as individual families, as Iain Guest from AP saw in November 2018 when CPIK distributed 51 cows at the remote Pokot village of Plesian. Villagers came out in force from both sides to pray at the church, dance, and accept praise from village elders and local government officials. For many it was also a chance to make new friends: after Esther Lenosilale (Samburu) with Eliza Amrara (Pokot), she visited Eliza’s home for the first time.

Heifers for Peace: CPIK gave out 51 cows in November to Samburu and Pokot families. The money was raised by AP Peace Fellows,

The main threat to this imaginative program comes from drought, which has decimated herds on both sides. CPIK’s cows have suffered a lower than normal death rate but they are still not immune. Kip Kiyeng (Pokot) joined Heifers for Peace in 2015 and received a calf from his Samburu partner in October 2018. A month later the animal died, in spite of three visits to the nearby government veterinarian. Kip was convinced that the calf had been ill when it was handed over, and planned to ask his Samburu friend for the next calf born to their joint cow. But he also understood that this would test of their friendship.

The Government’s Role

Government will play a key role in encouraging inter-ethnic cooperation in Baragoi. As noted above, government came late to Samburu County and officials made many early mistakes in handling the tribal conflict. But the Pokot-Samburu peace shows how it could be done differently. This starts with the police, whose heavy-handed response to cattle raids in Baragoi has created enormous resentment. Ben Karanja, the police chief in Langewon (Samburu) said that there had been 17 cases of theft in the village in the first six months of 2017, almost all by Pokot, but that over 90% had been resolved by the community. The last murder to occur in Langewon had been in 2012. Ben is in regular contact with his counterpart of the Pokot side, but they only step in when things get out of hand, which almost never happens. It probably helps that the two officers are not from either tribe.

Government can also help to deepen peace by recruiting teachers from both tribes (which encourages integration) and by providing licenses for common markets. But such a combination of restraint and intervention requires a subtle touch and self-confidence, which have been lacking in Baragoi since the massacre of 41 police by raiders in December 2012.

Working with the local government will be one of the many challenges facing CPIK in Baragoi. The organization has developed an excellent relationship with government officials in Maralal, the County capital, and officials in the (sub-county) Baragoi have hinted that they would welcome CPIK’s mediation. But CPIK is well aware of the need to remain independent. No doubt this will test CPIK’s skills even further during the months and years ahead.

The CPIK Team

Children Peace Initiative Kenya (CPIK) was launched in 2011 by Hilary Bukono to promote peace in the Northern Rift Valley of Kenya. In the years since, CPIK has worked with five tribes – the Gabra, Rendile, Turkana, Samburu and Pokot – and conducted over 100 inter-community peace activities with children, parents and teachers, including 12 peace camps. These have reached approximately 250,000 beneficiaries, including the more than 3,000 children who have attended camps. CPIK has a head office in Nairobi and has received funding from Rotary International, the Catholic Organisation for Relief and Development Aid (Cordaid), Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA),the University for Peace in Costa Rica (UPEACE), The Advocacy Project and Tangaza University College in Kenya.

The following profiles are adapted from a 2017 blog by Talley Diggs, who worked at CPIK as a Peace Fellow in 2017.

Hilary Bukuno

Hilary brings 15 years of experience of peace-building to his role as director of CPIK. He was born in the northern region of Marsabit and worked for Caritas at the Catholic Diocese of Marsabit as Coordinator of Justice and Peace Office. He also holds a Master’s Degree in Peace Education from the UN University for Peace in Costa Rica.

Hilary launched CPIK in 2011 after meeting Jane and Monica Kinyua, who were on a visit from Nairobi to work with refugee children. He was struck by the fact that children are rarely involved or mentioned in conflict resolution. Together they decided to change this.

Hilary is from the Gabra, one of seven tribes in Samburu County that have experienced conflict. This gives him credibility, contacts, and a deep understanding of the root causes of violence: “I understand the pastoralist conflict and the dynamics that shape the conflict,” he said.

Hilary’s knowledge of the pastoralist way of life also informs CPI’s approach to conflict resolution. “Pastoralist communities depend on livestock for their survival and this shapes their perception, belief and understanding about life. They speak different languages but use common symbols and images. I understand this language as a pastoralist and it helps me to easily communicate with them.”

CPIK’s first Peace Camp took place in February 2012 in the Samburu village of Longewan and brought together Samburu and Pokot children. It remains one of Hilary‘s most enduring memories. He recalls the camp: “Both groups were so scared of each other on the first day. Their testimonies of war were heartbreaking. That meeting of Pokot and Samburu children at the Peace Camp in 2012 was a life-changing experience.”

|

Monica Kinyua

Monica has a heart of gold but is also tough-minded and practical. As a result she and Hilary complement each other perfectly and make a dynamic team. Her generosity knows no bounds. She greeted me (Talley) at the airport and she made me feel at home in Kenya since my first day. One of the highlights of my time in Kenya was a weekend spent at her home in Kirinyaga County exploring tea plantations.

Monica is a Rotary Ambassadorial Scholar and she holds a Master’s Degree in Peace Studies from the University of San Diego, California. But her real passion is children. She is a trained teacher and has several years of experience working with children.

The idea of CPIK was born when she and her twin sister, Jane, visited Marsabit. It was on this trip that they met Hilary, who saw them playing with children and got the idea for a peace-building program built around children. Ever since, she has worked hard to help to help Hilary build CPIK into a successful organization. She has a natural talent and ease when it comes to teaching. I love watching her engaging with our beneficiaries and bringing joy to CPI Kenya’s activities.

|

Jane Kinyua

Jane is CPIK’s Program Director. She and Monica are twins, which gives a family feel to the office. She acknowledges the benefits of working with her twin: “Shared dreams and visions have made us great friends beyond being sisters. We offer each other great support and complement each other highly.”

The best way to describe Jane is as a people person. She is empathetic and thoughtful when interacting with beneficiaries in the field. She cares deeply about their stories and values their experiences. She is currently working on a book that tells the stories of the families who have been impacted by CPI Kenya.

Jane has worked with young people who were acquitted for juvenile crime as part of a government program to rehabilitate young people under CEFA, an international NGO, for 3 years. In 2017 she followed her sister to the Kroc Center at the University of San Diego to pursue a Master’s degree in Peace Studies. “I hope to gain new knowledge and skills that will help CPIK to measure the impact of our programs our value to beneficiaries,” she says, adding that she plans to focus on the role of women in peace building. Working in the US will, she hopes, will enable her to promote CPIK’s work outside Kenya build a network of American support.

|

Supporters

With many thanks to…

2017 Supporters:

Kathy Allen, John Altin, Claiborne and Marian Barksdale, Jack Barksdale, Caroline Battle, Nancy Boelter, Kilby M. Brabston, Katherine S. Brooks, Caroline Conley, Kathleen Conroy, Carrie Coulson, Barbara Couture, John M. Danskin, Timothy S. Davidson, Victoria Demetropoulos, Francesca G. Diggs, Stephen T. Diggs, Mary Elizabeth Diggs, Liza Edgerton, Ann Marie Edlin, Barbara Ellard Dziedzic, Cale Ettenberg, Beverly Putnam, Sandra Filer-Gothie, Sophie Gibson, Cornelis Gispen, Katya Danielle Gothie, Martha Guariglia, Rhonda Guinazzo, Michelle Hunter, Interactions for Peace, Lauren Iskander, Beth S Kitchings, Marianna K. Lee, Catherine Lowance, Julia G. Moore, Seeley O’Connell, Stephanie Osborne, Tay Parng Chien, Elizabeth Farish Percy, Mary M. Poe, Margaret A. Revelle, Rebecca Rodriguez, Amy Rouquette, Amanda Roussell, Mary Margaret Sanders, Valerie Scarborough, Richard Scribner, Anne Spencer, William Spicuzza, Katya Spicuzza, Katya Spicuzza, Francesca Talley Diggs, Charles Thompson, Elizabeth Tinsman, James Tuttle, Barrie Welty, Lee Wood, Raymond Yates

2018 Supporters:

Richard Bainter, Anita Bakula, Olga Barnes, Kathy Bayer, Philip L. Behe, Christopher Carr, Tom Carver, Jordan Castleberry, Justin Castleberry, Silvio Cenzi, Melissa Colby, Dinorah Costa, Helen Crump, Deborah Dutilly, Dario Gallo, Stephano Giudici, Donna Herberger, James Herberger, Tom Herberger, Patricia Hormell-Brinkman, Lulu Hsu, Lawrence Ingeneri, Monica Kinyua, Theresa Layer, Jennifer McNab, Riley McNab, Cynthia Moran, Robert Robbins, Ann Robbins Gordon, Erin Rocha, Lauren Schulz, The Law Offices of Michael J. Herberger, Roger N. Vargas, William Wallinovich, Miranda Williamson