ADVOCACYNET 367, August 17, 2021

Afghan Betrayal

How We Broke A Promise to Women and Girls in Afghanistan

Commentary by Iain Guest

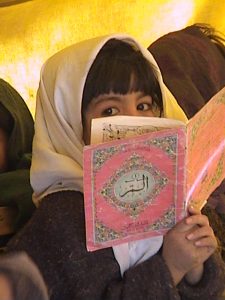

Sixteen years ago, in October 2005, I found myself on a mountain in Wardak province, Afghanistan. Facing me were two rows of girls sitting cross-legged on the ground (photo). Nearby were the ruins of their school, which had been burned down because of a land dispute.

As the wind whipped up the dust, the girls had their text books open and were following their teacher with serious expressions. One student told me through an interpreter that she had walked several miles to attend this open air class. She was not to be denied.

I was smitten. There is no other word for it. High up in this spectacular setting, these girls were rejecting centuries of discrimination and turning their right to education into something personally empowering – in the face of enormous odds. I vowed never to take education for granted again.

The girls were also lucky in their leader, one of the most inspiring women I have ever met. She was born during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, spent much of her early life in a refugee camp in Pakistan and returned in 2002 with a burning determination to educate girls. It started in the living room of her family home, high up in Wardak.

Over the past twenty years, she has put almost 4,000 girls and mothers through schools and literacy centers. Every school had been a labor of love and fraught with difficulty. But I remember sitting there on the mountain and thinking – this might just work. I also realized that the effort was bringing new purpose to my own endeavors.

*

Such is the appeal of girls’ education in Afghanistan. Hundreds – perhaps thousands – of aid workers have passed through the country since 2002 and no doubt felt as I did. In 2001 there were less than 900,000 students in Afghan schools and all were male. By last year the number had risen to 9.5 million and 39% were girls. Even allowing for exaggerations and “ghost” enrollments that is impressive.

Unfortunately it is also irrelevant, at least for now. Now is not the time for self-congratulation. Now is the time to be clear-eyed about the disaster in Afghanistan, and remind ourselves that we put a target on the back of these girls.

It is hard to overstate the horror of this moment. The photos of desperate Afghans clinging to planes – so reminiscent of Vietnam in 1975 – speak for themselves. By some accounts the Taliban march on Kabul has been marked by summary executions, forced marriages, rape and the enslavement of girls. I have seen no hard evidence that the Taliban have permitted girls’ education in any of the territory they have taken.

And why would they? They will remember the humiliation of their defeat in 2001, the detentions at the Bagram air base and the notorious center at Guantanamo Bay where detainees were denied legal protection and Korans were flushed down the toilet. Of course they will take out their fury on women and girls, who symbolized the West’s ambitions.

*

How did it come to this? For me it began with Laura Bush, whose embrace of girls’ education in Afghanistan offered a welcome palliative after 9/11. Mrs Bush did for girls in Afghanistan what Hilary Clinton’s 1999 visit to the Eastern Congo did for victims of war rape.

The two first ladies were certainly effective at shining the light on women’s rights and mobilizing resources, but that’s not what I think of right now. Instead, I think of self-promoters who jumped on the bandwagon like Craig Mortenson, lionized by the New York Times and others for his efforts to promote girls’ education until he was exposed as a fabricator and liar.

I think of the American NGO conglomerate International Relief and Development that was entrusted with $2.4 billion dollars of US aid in Iraq and Afghanistan until a USAID investigation found that its director and wife had pocketed almost $6 million.

These were extreme examples, of course. But even for the well-intentioned, Afghanistan always carried the whiff of adventure. We have to ask ourselves whether this was appropriate and whether it contributed to the peril now facing our Afghan friends.

*

The core problem has always been that the US was never really committed to building a civil state in Afghanistan, Laura Bush notwithstanding. The mission from the start was military and the goal was always to kill Bin-Laden and defeat the Taliban. Even that lost some urgency after the US invasion of Iraq in 2003.

NATO, a military alliance, found itself drawn into a mission in Afghanistan – half peace and half war – that was completely inappropriate. This diluted the efforts of European members of NATO that were far more committed to the civilian mission than the US.

It also led to some far-reaching blunders. One was committed by the Germans, who relaxed a long-standing policy against foreign military adventures in order to pull their weight in the Afghan war. This looked like a serious mistake in 2009 after a German airstrike killed scores of Afghan civilians in the province of Kunduz.

The civilian mission in Afghanistan kept butting up against the military imperatives and losing. So many Afghan wedding parties were bombed by NATO airstrikes in the early years that it began to look like a deliberate strategy, and hence a war crime.

Americans were outraged when the International Criminal Court decided to investigate US forces in Afghanistan in March 2020, but the decision was taken with reluctance rather than glee. To have ignored the evidence would have cast serious doubts on the Court’s credibility.

According to the UN Mission in Afghanistan, airstrikes by the Afghan air force and NATO continued to kill Afghan civilians to the bitter end. Of course, the Taliban killed many more, but they were not doing the noble work of building peace.

One device used by NATO governments was the deployment of “provincial reconstruction teams” to spur development in provinces under their military authority. This produced a policy patchwork that made any national aid effort next to impossible. Some of the teams were led by soldiers and others by civilians. This blurred the line between military and civilian and exposed more neutral aid workers to serious risk.

The saddest experiment in pacification, for me, was known as “Human Terrain.” This embedded social scientists in military patrols and took the life one of my first students at Georgetown, Paula Lloyd, who was doused with gasoline during a visit to a village in 2008. Paula later died of her burns. Her parents created a foundation to support girls’ education in her memory.

*

In spite of this trail of tears, I cannot understand the reasoning behind Biden’s abrupt decision to pull out American troops or the unquestioning acquiescence of European allies. I opposed the invasions of Vietnam and Iraq, but found it easier to came to terms with the overthrow of the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001 precisely because it was quickly followed by the promise to empower women and girls.

Even now I feel that the US/NATO presence – for all its flaws – served as a stabilizing influence. Look no further than the savage bombing of the Sayed ul-Shuhuda school for girls in Kabul on May 8, shortly after Biden announced that the US would withdraw by September 11.

What is the logic behind Biden’s decision? The last American casualties in Afghanistan occurred in early 2020 and the risks had been whittled down to near zero. The US has maintained troops in Korea and Germany for over 70 years. Could it not have stayed longer in Afghanistan to buy time for a concerted push for peace? The answer was no. Americans wanted out and Biden’s heart was never in it. The promise made to Afghan women in 2001 was ignored.

Americans describe Afghanistan as America’s longest war, and bemoan the cost in blood and treasure. It has certainly been appallingly high. But the mission was urgent and vital to women and girls. Afghans I met had no interest in reviewing Afghanistan’s history as a graveyard of imperial ambitions, from Britain to the Soviet Union. Instead, they would cock a quizzical eye and ask me to focus on the here and now. They understood that every day spent at school by a girl was an achievement. Unlike many aid initiatives, success was also easily measured.

I heard much the same from US Army veterans who served in Afghanistan and later passed through my class at Georgetown. They seemed to feel that the protection of civilians had brought credit to their own efforts. I imagine they will not be pleased when their successors supervise the evacuation of Americans while Afghan girls are left to their fate. Whatever the domestic political gains from withdrawal, Afghanistan will leave an indelible stain on Biden’s legacy.

*

The world is now facing a full-blown humanitarian catastrophe in Afghanistan. Depending on the Taliban’s next moves, all options should be on the table, including even the creation of a safe haven inside Afghanistan. Who better to make this case than Samantha Power, the head of USAID, who argued eloquently for humanitarian intervention earlier in her career?

The Biden administration has set up a new refugee category for Afghans who worked with American NGOs, and that pledge must be honored by this and future administrations. But the US will only consider applicants once they reach a third country and it will not be easy for women to escape the noose. Pakistan has sponsored the Taliban and may not want to incur their wrath. Iran is hostile to the US. It will take money and humility to persuade both governments to open their doors to Afghan refugees once again.

Europe too must pull its weight, although early signs are not promising. Just last week six European governments demanded that the European Union continue to deport Afghan asylum seekers, even as the Afghan government was collapsing. The decision was reversed a few days later.

*

And what of the aid community? We must take our cue from Afghan women leaders and do everything in our power to support and encourage them. Those who can will escape, regroup and appear at international conferences, showing the same passion and dignity they have shown throughout. They should be listened to with respect and admiration.

We should also understand that the global mission to educate and protect women and girls is more urgent than ever, and vigorously challenge governments like Britain which recently cut its contribution to the UN Population Fund by 85%.

At the personal level, this disaster must provoke serious soul-searching by those who answered the call after 2001. If they were in it for ego, or what is sometimes called the “White Savior Complex,” then they were complicit. But if they responded to a request by a local partner, it was entirely appropriate. Would that everyone could experience the thrill of seeing girls at school in the Global South.

But such partnerships must be based on mutual respect. The problem with North-South aid is not the personal motives of aid workers, but the assumption by donors that they can impose an agenda. Afghanistan shows that this is dangerously misguided, not just because Northern politicians are untrustworthy but because the moral authority in any North-South partnership must always lie with the local partners who put their lives on the line. The closer you get to such people, the clearer this becomes – and the harder it becomes to walk away if it all goes wrong.

Which raises the following question: should we have made that promise in 2001, knowing that the ultimate outcome would almost certainly be beyond our control? I put this to our Afghan partner, who launched the Wardak school program and has been able to escape Afghanistan. Would she do it all again knowing how it ends?

“Absolutely,” she replied. “What we did is irreversible. Once girls and mothers have been educated, you can’t turn the clock back.”

Iain is Executive Director of The Advocacy Project. Visit his blog page to comment on this piece. (Photos by Iain Guest)