ADVOCACYNET 381 June 13, 2022

The Loneliness of Albinism

A young mother hides her newborn as she breastfeeds. Husbands abandon their wives when they first see the color of their child’s skin. Neighbors describe children with albinism as “money,” referring to the imagined value of their body parts. Classmates steal sunscreen from students with albinism even though it protects them against cancer.

Fridah Marauni was shunned by her husband’s family after she gave birth to a daughter with albinism. Her husband shows his anger

These are among twenty poignant portraits of albinism in Kenya which have been embroidered by members of the Albinism Society of Kenya (ASK) the country’s leading advocate on albinism, with support from The Advocacy Project (AP). Their stories are published today (June 13, 2022) on International Albinism Awareness Day in the hope that they will help this misunderstood minority to enjoy better protection.

ASK describes albinism as “a group of inherited conditions caused by a lack or deficiency in melanin, the pigment that protects us from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays. This can result in physical characteristics like white or light blond hair and very pale skin that is particularly sensitive to the sun.”

Precise figures are hard to come by, although the 2019 Census on Kenya put the number of Kenyans with albinism at 9,729 – one for every 4,890 Kenyans. The ratio in most northern countries is thought to be around one to 15,000 – 20,000.

Albinism in Africa has long been associated with violence, owing to the belief that the body parts of people with albinism can ward off evil spirits. As with child sacrifice, such superstitions have been exploited by ruthless traffickers and witch doctors.

One 2009 report by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies stated that a complete set of body parts from a person with albinism including “all four limbs, genitals, ears, tongue and nose” could bring in up to $75,000 on the black market.

The level of violence has fallen sharply as international awareness has grown, and in 2015 the UN Human Rights Council created a new post to investigate acts of hate and discrimination linked to albinism. Still, the threat from trafficking remains real. Based on replies to a questionnaire, a 2021 report by the UN found that myths about albinism had caused 208 people to be murdered and 585 attacked across 28 African countries between 2006 and 2019.

Kenya is at the forefront of African governments seeking to protect people with albinism and advocates were elated when the government included albinism in the 2019 census. The Kenyan government also funds the National Albinism Sunscreen Support Program which currently provides free sunscreen to around 4,000 people. But as the embroidered stories show, the need for sympathy and protection – legal, medical and social – remains urgent, even in Kenya.

The fear of trafficking is deeply ingrained and the artists are used to hearing their children described as “money” in reference to their body parts. Everlyn Narotso has been told that her 12 year-old son Rodrick could serve as a “charm to boost business.” Yvonne Wanjiku is afraid to leave her son Prince, 5, when she goes to work.

Even when they are not directly threatened many of the artists feel isolated. Often the stigma comes from their families.

Of the 20 artists, eighteen are mothers and no fewer than twelve were abandoned by their husbands. Most were shunned by their in-laws and several have even been harassed by their former husbands.

The isolation even extends to places of sanctuary. When she visited a hospital, Esther Wambui was asked by a nurse if she would like help in selling Hope, her 4 year-old daughter. Other parents have confronted Esther at church and asked her if Hope’s albinism is contagious. It is not, but Esther had to lie in order to avoid further harassment.

School can also be a challenge. Esther gave one of Hope’s teachers sunscreen for Hope and asked the teacher to help her put it on, but Hope still came back home with sunburn.

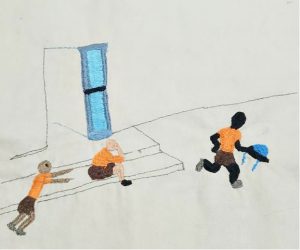

Rodrick Narotso is bullied at school because he has albinism. Here, classmates steal his hat, which protects him against the sun

The children themselves can also face bullying. Rodrick Narotso, 12, has his sunscreen stolen by his classmates. Carolyn Nyambura’s story shows a student with albinism who refuses to raise his hand in class because he knows he will not get called by the teacher.

Although the overall mood of the stories is overwhelmingly sad, there are some heart-warming exceptions and acts of kindness.

Julia Withera learned about albinism while studying as a beautician and has since become an enthusiastic advocate. Rachel Njoroge, a mother of three, volunteered to raise her brother’s son Kylan, who has albinism, and has been enriched by the experience.

Although albinism is now firmly on the UN’s human rights agenda, legal protection alone is not enough to address the full range of threats depicted in the stories.

The medical threat is particularly severe because the eyes and skin of people with albinism are sensitive to the sun and this increases the risk of cancer. (One UN report describes persons with albinism as “visually impaired.”) Poverty is also a problem, because so many mothers are single and lost their jobs during the pandemic, making it harder for them to purchase sunscreen and protective headgear.

This presents ASK with some clear advocacy targets and the organization is pressing the Kenyan government to increase the subsidy for protective sunscreen. But empowering the mothers is equally important, and telling their stories alongside other mothers who are under the same pressure was an important first step. Whenever Liz Awor felt stressed during this project she would revert to embroidery to “immediately help her relax.”

The program will now move from story-telling to income-generation. Several artists want to join the Kibera composting project. AP will also offer further embroidery training in Nairobi in July and is exploring a proposal to train mothers to make bucket hats.

The embroidered stories have been assembled into two powerful advocacy quilts by Christine Danler in North Carolina (photo left) and Jane Cancilleri in Massachusetts. Ms Danler told AP that she had been profoundly moved by the stories, and that her design used white circles to show that “we are all connected by our humanity.”

Meet the artists and learn their stories