Partner Profiles

Abagail

Abagail

Abagail lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. Her brother and his wife, both HIV+, recently passed away, leaving her with six children to care for. “Surviving is really a challenge,” Abagail told WAP, “I am the only one remaining in my family to care for the six orphans.”

Agnes

Agnes

Thirty-five-year-old Agnes was born in rural Zimbabwe but now works in Chitungwiza, a town outside Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) operates. “I was 16 when I first married,” she told WAP. “I wasn’t going to school. There were eight in my house and I was the sixth child. My mother died and after that I had no support. At that time, I came across a man who was mature, so I decided to get married.” Agnes now has three daughters aged 17, 14, and 10. She and her husband separated in 2008 and he eventually moved to Botswana and married another woman. Agnes could not support the children on her own in their village so she moved to Harare to find work. “I left the children with my sister,” she said. “I had no choice but to leave the children while I work but it’s very hard not to be with them.”

Akatendeka

Akatendeka

Akatendeka lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She married when she was 17 years old. “I had lost my parents and was working as a house maid. No one was supporting me,” she told WAP. “So, I decided to get married.” Akatendeka and her husband later divorced, and she now supports their two children by selling second hand clothes in the market.

Anashe

Anashe

Fifteen-year-old Anashe lives in Epworth, a neighborhood in Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school in June – a week before this photograph was taken – because her family was unable to pay her fees. “My favorite subject was science and I had hoped to become a doctor when I graduated,” Anashe told WAP.

Andowia

Andowia

Andowia, age 19, lives in Mbare, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She was 16 and in Form 4 when she had her first baby. Andowia left school because she got pregnant and could not afford to pay her fees, which were $80 per term for seven subjects. “My favorite classes were history and English. I had wanted to be a human rights lawyer,” she told WAP. Andowia cannot find work and she and her children are currently being supported by her mother. She hopes to find an employment opportunity, so that her children can finish school.

Aneni

Aneni

Fifteen-year-old Aneni lives in Epworth, a neighborhood in Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school four years ago when she was in Grade 7. When asked what she knows about child marriage Aneni says, “I think it’s not a good thing, people who marry young have a lot of challenges. My older sister got married at 15, she’s been married for 5 years now. Sometimes her husband will leave the house for long periods without telling her. That’s why I dislike the idea of getting married at a tender age.”

Angeline

Angeline

Thirty-one-year-old Angeline lives in Chitungwiza, a town outside Harare where the Woman Advocacy Project (WAP) works. When she was 17 years old, Angeline’s aunt spotted her walking home from buying vegetables with a boyfriend. The aunt told the rest of the family, who then forced her to marry the boy. Angeline is still with her husband and they now have five children. She supports herself by selling vegetables in the market and says she’s focusing on paying school fees for her oldest child, who is 14 and in Form 2.

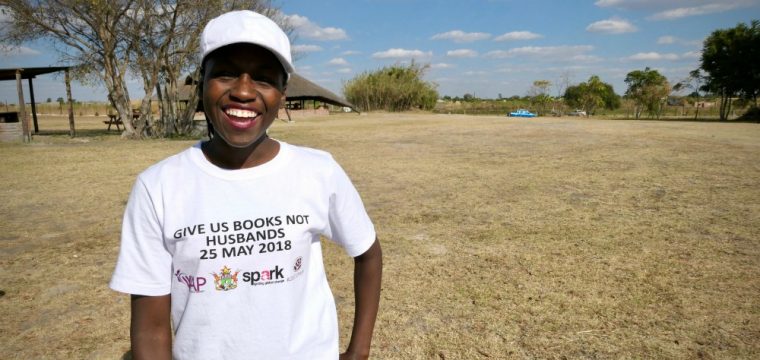

Auyanerudo

Auyanerudo

Nineteen-year-old Auyanerudo lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. Auyanerudo’s favorite subjects were History and Shona. One day, she hopes to attend university. She now spends her time taking care of her niece while her sister sells second-hand clothes in the market. Auyanerudo has attended WAP’s “Stand Up, Speak Out” anti-child marriage trainings and also participated in WAP’s recent “Give Us Books, Not Husbands” march. “Girls think marriage will fix their problems, but it makes more. Marriage isn’t the solution,” she told WAP.

Blessing

Blessing

Blessing lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school after Form 3 because her family was unable to pay her school fees. Blessing married at age 20 and has a baby daughter. Blessing does piece work when she can and would love to have a job selling firewood. “I hope my daughter can at least be able to go to school, that way she will be able to sustain herself,” Blessing told WAP.

Charity

Charity

Sixteen-year-old Charity lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She got pregnant at age 14 when she was in Grade 7. When her parents discovered the pregnancy, they reported her boyfriend to the police. The case, however, could not proceed because Charity does not have a birth certificate. In Zimbabwe if you do not have an ID and a birth certificate it is difficult to be recognized before the law as a citizen. Now Charity and her 2-year-old son live with her father, who helps support them.

Chido

Chido

Nineteen-year-old Chido lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She is in Form 6 and studying geography, economics, and business. Chido hopes to do a program in banking and finance after she graduates. “My biggest challenge is paying the fees,” she told WAP. “My father passed in 2015 and my mother does buying and selling in the market to help me.”

Chipo

Chipo

Sixteen-year-old Chipo lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. “I dropped out of school because I got pregnant at 16. I was in Form 3,” Chipo told WAP. “My boyfriend ran away to South Africa when he found out.” Chipo gave birth two weeks before this portrait was taken. She and the baby now live with her mother.

Chiwoniso

Chiwoniso

Nineteen-year-old Chiwoniso lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. “My mother passed when I was three and my father passed when I was eight,” she told WAP. “There was no one to care for me, so I went to live with my sister in the city.” When Chiwoniso was 10, her brother-in-law raped her. Her sister did not believe her and accused Chiwoniso of lying about the rape. “After that, I wanted to go out and to find a husband because I was afraid of my brother-in-law.” Chiwoniso got pregnant at 15 and now has a 4-year-old child who lives with her grandmother. She works in Harare as a housemaid.

Chihedza

Chihedza

Twenty-eight-year-old Chiyhedza lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She and her husband have three daughters – an eight-year-old, a 5-year-old, and a 2-month-old baby. Although Chiyhedza’s husband owns a vegetable stall in the market, they are having trouble raising the $30 necessary each month to pay for their two eldest children’s school fees. Chiyhedza says she loved school but had to leave in Form 3 after her father died, and her mother was unable to afford the fees. She recalls that her favorite subject was science. “My wish for my children is for them to go to school,” Chiyhedza told WAP. “My wish for myself is to one day return to school and complete my ordinary level.”

Danai

Danai

Danai lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school before she wrote her Form 4 exams because her parents could not raise the $75 necessary for the fee. Zimbabwe’s unemployment rate is over 80% and like so many of the women WAP works with, Danai isn’t working. She lives with her aunt and hopes to one day start a small business raising chickens.

Dorcas

Dorcas

Dorcas, age 17, lives in Mbare, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. Dorcas completed her ordinary level in school but failed to sit for the final exam because she was unable to pay her school fees. She begins to cry when she talks about how she wants to return to school and finish her studies. Her favorite subjects were food and nutrition and she had once hoped to be a journalist. Dorcas now owes the school over $1,000 in overdue fees.

Edith

Edith

Thirty-two-year-old Edith lives in St. Mary’s township in Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. As a single mother she is having difficulty supporting her two sons and paying their school fees. “We owe money to the school,” Edith told WAP. “My 13-year-old owes $120 and my 7-year-old owes $160. I just want to work, I would do anything.”

Elizabeth

Elizabeth

Fifteen-year-old Elizabeth lives in Epworth, a neighborhood in Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She is currently in Form 2, but says her family is having trouble paying her school fees. When she grows up she hopes to become a flight attendant.

Faith

Faith

Nineteen-year-old Faith lives in Mbare, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school in 2016, shortly after her father died because her mother was unable to pay her school fees (roughly $100 per term.) “When I was young, my dream was to sew things. My favorite class was fashion,” Faith told WAP. She had hoped to be a professional designer making jeans and long dresses. Like many of the woman WAP works with, Faith married as a child because her parents were unable to support her. “I got married in 2016, right after my daddy died,” she explained. Faith now has a one-and-a-half-year-old son.

Fadis

Fadis

Fifty-three-year-old Fadis lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. “I got married when I was 16 years old during the war. There was no school and the conflict forced us girls to get married,” she told WAP. Fadis owns a sewing machine and used to support herself by making clothes. Now she says that there are too many cheap second-had clothes for sale in the market and she can no longer make a profit. “I’m facing many challenges. I am the only one left in my family and I am caring for a number of orphans.” Fadis says. Her brother and sister have both died and she is taking care of their children.

Fadzai

Fadzai

Fifteen-year-old Fadzai lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school in Form 2 after her father died and her mother went to work in South Africa. Fadzai now lives with her grandmother and they support themselves by selling “Freeze-its” (frozen popsicles) in the market. Fadzai’s favorite subject was science and she had once hoped to become a doctor. “What is most difficult for me is the issue of my education,” she told WAP. “I want to go back to school like the other children, when I see them going to school I feel such pain.”

Grace

Grace

Nineteen-year-old Grace lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She is in Form 4 at school and her favorite subject is science. “We learn a lot about our health and the functions of our body, it’s very interesting,” Grace told WAP. Grace hopes to become a primary school teacher after she graduates – but this dream is in jeopardy. Her parents are divorced and Grace lives with her 25-year-old brother who works as a carpenter and supports her education. “I face a limitation due to lack of finances,” she says. “My brother is having challenges with money, so I’m only registered for four subjects this term.” Each of Grace’s subjects costs $50 and she explains that it has been very hard to find the money. When asked if she has considered marriage Grace says, “I don’t want to get married. My desire is to finish my education.”

Immaculate

Immaculate

Immaculate lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She is 15 years old and not in school. “I loved school, I used to go to school,” Immaculate told WAP. “I did up until Grade 6, but there are nine in my family and my parents could not afford the fees.” When asked what she knows about child marriage Immaculate is resolute, “I’m not interested in anything called marriage, I want to go back to school.” Her opinion has been shaped by the experiences of friends who married young and who Immaculate says now face many challenges. “Last month, one of my friends was forced to marry at age 15 because her mother heard that she had been seen out with a boyfriend.” Unfortunately, this situation is all too common in the areas where WAP works.

Irene

Irene

Seventeen-year-old Irene lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school in 2015 when she was in Grade 6. “My mother became sick, there was no one to take care of her, so I had to leave school,” Irene told WAP. Irene’s mother passed away earlier this year and she is now doing domestic work to help support her family.

Joy

Joy

Eighteen-year-old Joy lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She married at age 15 after her father died. “I was living with my grandmother in difficult conditions,” Joy told WAP. “Sometimes I would sleep without food, I would sleep outside. My solution was to get married. I thought to myself: if I get married I can at least help my mother.” Joy’s husband works as a shopkeeper at a small truck shop and they now have a one-year old son. Joy isn’t working and misses school. She recalls that her favorite subjects were math and science. “I had hoped to be a medical doctor, I wanted to help people,” she says. “If I’m given an opportunity to go back to school, I know I would do better than all the others. I know I am smart.”

Judith

Judith

Fifteen-year-old Judith lives in Epworth, a neighborhood in Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She dropped out of school last April when she was in Form 3 because her family could not afford her fees. Judith’s favorite subject was Accounts. “Now I am doing nothing, I am just around reading books at home. I’ve been reading exercise books from school,” she told WAP.

Karen

Karen

Eighteen-year-old Karen lives in Epworth, a neighborhood in Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She’s currently in Form 6 and hopes to one day become an accountant. In school she is studying the relevant subjects: accounts, business studies, and economics. When Karen was younger, she lived in a rural village and had a boyfriend. “When I moved here, my Auntie grabbed me by the ears and warned me off boys saying, ‘this is Harare.’ Now I have no boyfriend.”

Makanaka

Makanaka

Twenty-six-year-old Makanaka lives in Mbare, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She was 13 and about to go to Form 1 in school when she got pregnant and married. At that time, Makanaka was staying with her grandfather. One of her grandfather’s sons was harassing her and she says she had no choice but to escape her situation by getting married. Makanaka now has three children, a 13-year-old, a 10-year-old, and a 5-year-old.

Marion

Marion

Nineteen-year-old Marion lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. Marion has attended WAP’s “Stand Up, Speak Out” anti-child marriage trainings and also participated in WAP’s recent “Give Us Books, Not Husbands” march. “WAP’s programs are important because of the knowledge you have gained. When I talk to 15-year-olds who are pregnant, I feel bad, because I know they will face challenges,” Marion says. She has taken WAP’s call for girls to be ambassadors for change in their own communities to heart and says that she now talks to her friends about the dangers associated with early marriage. “We need to be educated as girls. We need to know that early child marriage causes poverty because of a lack of education.”

Mary

Mary

Seventy-four-year-old Mary lives in Mbare, a high-density southern suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. Her husband died 20 years ago, and ever since she and her family have been struggling to survive. “We have a lot of challenges because no one has work, there is nothing to do,” she says. Zimbabwe’s unemployment rate is currently over 80%. None of Mary’s six children are employed. “I used to sell vegetables, but now it’s difficult for me. I can’t do that business anymore because I’m asthmatic and have pain in my legs. But if I had an opportunity, I would want to do more business,” she told WAP.

Mazvita

Mazvita

Seventeen-year-old Mazvita lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school after Grade 7 because her family could not afford the fees. Now she does part-time work washing clothes. “I liked school” Mazvita told WAP. “If I get an opportunity, I’d like to go back because I want to be a teacher.”

Memory

Memory

Twenty-three-year-old Memory lives in Mbare, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She was in her first year at Bindura University studying banking and finance when she got pregnant. “I did not intend to have a baby,” she told WAP. “I’m not married, I don’t know where the father is.” Memory dropped out of university because she could not afford the fees, which including housing were about $900 per semester. She now sells frozen popsicles to support herself and lives with her mother. Given the opportunity, Memory would like to finish her four-year university program. Her ambition was to become a financial manager and start her own business.

Mudiwa

Mudiwa

Nineteen-year-old Mudiwa lives in Epworth, a neighborhood in Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She married at age 18 and now has a 9-month-old baby. “I left school when I got pregnant,” Mudiwa told WAP. “When my father found out, he chased me away saying, ‘I do not want to see you.’ So, I had to get married.”

Neneris

Neneris

Nineteen-year-old Neneris lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school last year because her family could not afford her fees. They still owe the school $150. “I was in Form 4, I would like to go back to school,” Neneris told WAP. Her favorite subjects were commerce and math and she had hoped to one-day become a bank teller. “It would have been a good job,” she said wistfully. Zimbabwe’s unemployment rate is currently over 80% and like many of the women WAP works with, Neneris is not working. She now spends her time learning to plait hair.

Noinyasha

Noinyasha

Twenty-one-year-old Noinyasha lives in Mbare, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She married at 18 and has a two-and-a-half-year-old daughter. Noinyasha’s husband used to be a football player, but now he is out of work. Like so many in the communities where WAP works, Noinyasha and her husband are having trouble supporting themselves. “I hope my daughter can do better than I have done,” Noinyasha told WAP, “she mustn’t live the way I have lived, she mustn’t struggle the way I have struggled.”

Nyarayi

Nyarayi

Twenty-year-old Nyarayi lives in Mbare, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She married at age 15 and had two children by the time she was 18. When asked why she married so young, Nyarayi explains that her parents had passed away and she was living with relatives who had their own children and did not love her. One day Nyarayi came home late and her relatives cast her out of the house, telling her to “go back where she had come from.” Shortly afterwards, she got married and left school. Nyarayi says that her favorite subject was mathematics, and that she had once dreamed of becoming an accountant. She hopes her daughter finishes school before getting married.

Nyasha

Nyasha

Seventeen-year-old Nyasha lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. When she was 15 she discovered she was pregnant and left school. Nyasha is a WAP beneficiary. She has attended a “Stand Up, Speak Out” anti-child marriage training and also participated in WAP’s recent “Give Us Books, Not Husbands” march. “I learned about child marriage and was taught how to help others not to become involved in child marriage. Now I am passing that information on to people in my community,” she said. Nyasha and her baby are supported by her father, who works as a carpenter. “I don’t want to get married,” she says. “My desire is to go back to school.”

Penelope

Penelope

Fifteen-year-old Penelope lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school last year when she was in Grade 7 because her family was unable to pay her fees. “Now I just sit. I want to go back to school,” Penelope told WAP.

Plaxedes

Plaxedes

Plaxedes, age 18, lives in Mbare, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school two years ago after she became pregnant. Plaxedes married earlier this year. She would like to go back to school but says that her husband would not accept it. “He would worry that I would go with someone else if I went back to school,” Plaxedes told WAP. Her husband is not working, so she is living in her aunt’s house. Plaxedes supports herself and the baby by selling second hand clothes, but this life is very difficult. She often goes to sleep without eating. In the future, Plaxedes hopes to get a good job, so she can feed her family.

Portia

Portia

Nineteen-year-old Portia lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school in 2016 after her father passed away and her family could no longer afford to pay her school fees. She now supports herself by selling vegetables in the market. “I’m not yet ready for marriage,” Portia told WAP. This opinion has been shaped by the experiences of several of her friends who married young. “They get married early because of harassment and bad treatment from their families. But there are many challenges for women who marry and give birth at a tender age, their muscles are not ready.”

Precious

Precious

Precious, age 22, lives in Mbare, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She supports herself and her two children by buying and selling goods in the market. Precious left school after Form 3 but hopes to one day go back.

Rejoice

Rejoice

Sixteen-year-old Rejoice lives in Epworth, a neighborhood in Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She dropped out of school during Form 2. “My mother and father divorced. My father is now in South Africa and my mother can’t pay the fees on her own.” Rejoice’s favorite subject was commerce and she had hoped to one day become a nurse. Now she spends her time at home while her mother buys and sells goods in the market. Rejoice has five siblings and none of them are currently in school.

Rose

Rose

Sixteen-year-old Rose lives in Chitungwiza, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school in May 2018 after her family was unable to pay her fees – roughly $150 per term including transport. Rose had hoped to graduate and one day become a mining engineer, because her father told her this was a stable job that made good money. “When I stopped going to school I was so pained. I was so affected because I’m good at school,” Rose told WAP. “I visit my friends who are still in school and ask them what they are learning.” Many girls decide to marry once they leave school, but this is not an option Rose is considering. “My mother taught me about child marriage,” she says. “There are a lot of challenges when you marry at a tender age. There is a lot of suffering in early marriage. You will always be disadvantaged because you won’t be educated, and people will look down on you.”

Rufaro

Rufaro

Twenty-one-year-old Rufaro lives in Epworth, a neighborhood in Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She married and left school at age 18 after discovering she was pregnant. “It just happened because I had no one to encourage me – no one to take care of me or help me with school fees,” Rufaro says when asked if she felt ready to marry at that age. Her husband works part-time jobs in construction and they have a three-year-old daughter. Rufaro says she would want her daughter to marry at the age of 25. “By that time, she’ll be learned and will be able to get a good and sustainable job. She’ll never have to beg her husband for money because she’ll be able to work for herself. Her husband will value her, and she will be a respected member of the family. When you have nothing, people regard you as nothing. I don’t want her to live like that.”

Ruth

Ruth

Ruth lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She got married at age 16 after discovering she was pregnant. She now has three children—a daughter and two sons. Ruth’s husband has a job molding bricks, but money is tight and they are having trouble paying their children’s school fees. Ruth’s daughter is now 16-years-old, the same age Ruth was when she married. “My wish is that my daughter completes school,” Ruth told WAP. “I would want her to get married at the age of 20, when she knows what life is all about.”

Shorai

Shorai

Shorai lives in Chitungwiza, a town outside Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She married at age 16 and was pregnant by age 17. “My parents died. I was staying with my grandfather, but there were too many grandchildren. We had no money for school, no money for food,” she told WAP. “This situation caused me to get married.” Shorai and her first husband divorced, and she is now married to another man. She faces challenges at home because her husband “comes and goes” and most of the time she is alone with her two children. Shorai washes clothes and does part-time work, but it is not enough to cover school fees. “I would love my children to go to school. I don’t want them to be like me,” she says. “I hope they wait to marry until they are 25.”

Spiwe

Spiwe

Spiwe, age 17, lives in Mbare, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She finished Grade 7, but left school last year because her family could not afford to pay her school fees. Spiwe lives with her grandmother, who is having trouble supporting her. “I want to go back to school,” she told WAP. “Now I do nothing. I’m feeling so much pain seeing young people of my age go to school.”

Tinotenda

Tinotenda

Tinotenda lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She married at age 17, after discovering that she was pregnant. “My boyfriend was the one who told me that I was pregnant, I didn’t know about those things then,” Tinotenda told WAP. When her father learned of the pregnancy, he threw her out of the house. Now at age 37, Tinotenda has 5 children. Zimbabwe’s unemployment rate is currently over 80% and like many of the women WAP works with, she is not working. “Before I got pregnant, I just wanted to go to school, support my family and my mother. Now I want to work so I can send my children to school. I don’t want them to lack knowledge.”

Venethy

Venethy

“Every term, at least one of my students would get married,” says Venethy, who teaches commerce. “One day, I went to a Woman Advocacy Project (WAP) anti-child marriage training – I was touched. I realized that I don’t need to convince all of Zimbabwe, I can start small, I can make change in my own classroom by just sitting down to talk to the girls at lunch.” Throughout the training, Venethy worked to create a relaxed and comfortable environment, explaining that she wanted her students to have fun, build confidence, and create a lasting network of support to help them resist early marriage. “We ask: girls, what is it to be a girl? Because they know best what the other girls are thinking, they are the best teachers,” Venethy said.

Vimbai

Vimbai

Eighteen-year-old Vimbai lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. When she was 15, her parents died and her life changed suddenly. “I had no choice,” Vimbai told WAP. “I had to leave school in the rural areas and move to Harare to live with my sister who was a sex worker.” One night, a man her sister had brought home raped Vimbai and at 15, she became pregnant. Vimbai never reported the rape to the authorities because her sister threatened her. She and her son now live with her aunt in Hopley. “I just want to work – do a business – and support myself and the baby,” Vimbai told WAP.

Wonai

Wonai

Fifteen-year-old Wonai lives in Epworth, a neighborhood in Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She left school in Form 3 because her family was unable to pay her school fees. Wonai says her favorite subjects were History and Shona. Many of the women and girls WAP works with married shortly after leaving school, however Wonai is not considering this option. “I want to marry at 23,” she told WAP. “I had a friend who married at 15. Now she is 16 and with a baby. Her life is very difficult. I learned from my friend.”

Yeukai

Yeukai

Eighteen-year-old Yeukai at an anti-child marriage training in Harare, Zimbabwe. The full day of activities included information about the consequences of early marriage, practice discussing the topic with friends, and a discussion of difficult issues including parental abuse – which can drive girls to seek refuge in marriage. Yeukai is in Form 6 and has been participating in Woman Advocacy Project (WAP) programs for over a year. “When I grow up, I want to be a human rights lawyer,” she told WAP. “I want to stand for women and for people with disabilities and albinism. Sometimes when I talk about injustice, people say ‘well that’s the way the world is,’ but I think no. Maybe I’m crazy, but I want to stand for justice.”

Zivanai

Zivanai

Twenty-eight-year-old Zivanai lives in Chitungwiza, a town outside Harare where the Woman Advocacy Project (WAP) works. She is a member of the African Apostolic Church and married at age 18. Her husband has two other wives. “His first wife has six children, his second wife has four,” Zivanai told WAP. “We all stay with him and each night he goes in a circle, from one woman to the next.” Zivanai has four children and is currently pregnant. Her husband doesn’t provide any financial support and none of her children are in school.

Zvikombrero

Zvikombrero

Zvikomborero lives in Hopley, a suburb of Harare where the Women Advocacy Project (WAP) works. When she was young, her father passed away, leaving her with a stepmother who mistreated her. She got married when she was 15 and gave birth at 16. “I was so young, I didn’t know the importance of school,” Zvikomborero told WAP. Zvikomborero’s first husband didn’t take care of her so she left to find work. “I used to work in the farms when the whites were still here,” she said. The farm where she worked was very remote and Zvikomborero says she gave birth to her second child while walking on the road to the nearest clinic. Zvikomborero is not currently working. She’s HIV+ and has also suffered from Tuberculosis. “I have a passport, but I’ve never used it,” she says. “Given the opportunity, I would want to work as a cross-border trader.”

sexual violence in 2012. Eighteen staff members work in the capital, Bamako, and are pictured right. Ten staff work at the center in Bourem. The turn over of staff has been very small, testifying to their dedication and experience.

sexual violence in 2012. Eighteen staff members work in the capital, Bamako, and are pictured right. Ten staff work at the center in Bourem. The turn over of staff has been very small, testifying to their dedication and experience.