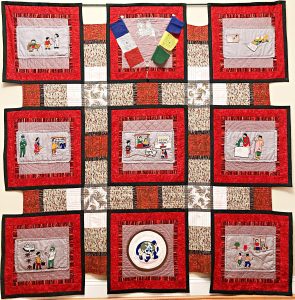

The Nepal COVID Quilt

Background

The seven blocks featured on this page were produced by three members of the Network of Families of the Disappeared, Nepal, who lost family members during the conflict in Nepal (1996-2006). The artists are among 30 women who learned to use embroidery as a means of expression and advocacy in 2016, with help from AP Peace Fellows.

These blocks describe their experience with COVID and were made in October 2020 by Sarita, Kushma and Alina in the town of Burigaon, Bardiya district, western Nepal.

We have told the tragic story of the Bardiya family members, and profiled the artists, elsewhere in this website. Between 2017 and 2019 they produced 20 embroidered blocks describing how their loved ones had been kidnapped and disappeared. These were assembled into two striking saffron quilts in 2019. One quilt remains in Nepal. The other has been widely shown, including at the United Nations.

Their next foray into art advocacy was to portray the tigers that live in Bardiya National Park. This produced three colorful quilts which are shown here. Several members of the cooperative then decided to use their skills to launch a bag buiness. Using funds raised by AP, they have produced 50 Tiger bags, which will shortly be put on sale in the US.

Using their artistic skills to describe the COVID crisis was a logical next step. COVID has taken a heavy toll in Nepal. As these pages are being written, Nepal ranks 37 in the world with 230,000 reported cases and 1,454 deaths. As we have reported, Nepal’s dependency on remittances from foreign workers has left the country and workers particularly vulnerable. Millions of Nepalis work in the Gulf region and in neighboring India.

Nepali workers abroad were allowed to return home in May. They then remained – like the rest of the country – in lock down until September 17. Conditions in the quarantine centers have been appalling, and employment opportunities in the villages non-existent.

Nepali workers abroad were allowed to return home in May. They then remained – like the rest of the country – in lock down until September 17. Conditions in the quarantine centers have been appalling, and employment opportunities in the villages non-existent.

The stark technique used in these blocks seems particularly appropriate for such a somber story. The precise thread lines and the empty spaces perfectly convey the isolation which has become the defining feature of the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 has separated friends, families and communities. It has turned other people – usually a source of joy and comfort – into a threat and object of suspicion.

All of this comes out in the blocks. In one, villagers visit a pharmacy which is under armed guard. In another, ageing parents sit alone and sad, no doubt missing their grandchildren. Women keep their distance while drawing water at the village pump, where they normally meet as friends. Hands appear at the windows of a hospital. Perhaps the most shocking image shows someone who is terminally ill from COVID-19, while his wife imagines what comes next – burial in a mass grave, without his family being present.

These stark and compelling compositions show the Bardiya artists at the height of their skills. They have used embroidery to create a new art form, not unlike the colorful Mithila art from northern India but without the cluttered background.

The squares were assembled into the spectacular quilt featured above by Ann Watson, a well-known quilter in North Carolina. Meanwhile, in parallel with this project two other AP partners have used embroidery to describe the pandemic. In Zimbabwe, ten girls have produced dramatic blocks from the communities of Chitungwiza and Epworth, which have suffered through a savage lock-down. Nine High School students in the US have also described the impact of COVID-19 on their lives in a series of compelling squares.

The squares were assembled into the spectacular quilt featured above by Ann Watson, a well-known quilter in North Carolina. Meanwhile, in parallel with this project two other AP partners have used embroidery to describe the pandemic. In Zimbabwe, ten girls have produced dramatic blocks from the communities of Chitungwiza and Epworth, which have suffered through a savage lock-down. Nine High School students in the US have also described the impact of COVID-19 on their lives in a series of compelling squares.

For more information contact Sarita (tsarita124@gmail.com) and Prabal (prabalthapa20@gmail.com). Our thanks to Prabal for transporting the blocks to the US and to Humanity United for supporting this project. (January 1, 2021)

Artists and blocks

ARTISTS

Sarita Thapa is the inspiration behind the Bardiya cooperative. Sarita was eleven when her father Shayam was denounced by a cousin as a Maoist and detained. Sarita, her mother and younger brother were then ostracized and driven from the village. Sarita gave up school to concentrate on the search for her father which has cost the family an estimated 200,000 rupees ($2,000). She endured further tragedy after her husband died from a snake-bite. But these misfortunes only stiffened Sarita’s resolve. Sarita is a strong believer in embroidery as a means of empowering women and has led the projects to produce 50 memorial squares and Tiger bags.

Alina Chaudhary was an infant when her father Hira Mani disappeared in 2003. Hira made furniture and earned 90,000 rupees a month – a significant amount. One day, he went to work at a neighbor’s house and never returned home. Soldiers came to the family home and questioned Manju, her mother. Manju was about to follow them when a neighbor stopped her, afraid that they would take Manju away as well.

Kushma Chaudhary was seven when her father Ton Bahadur was taken from home by soldiers at night. She does not remember the incident, but her mother has described it many times: “The army came to my home, took my father away and beat him.” Kushma’s father was another victim of a local score. He was not a Maoist, but active in social work in the community. He won a local election and got into an argument with an unsuccessful candidate who denounced Bahadur to the army. Ton had many friends in the village, but the army did not investigate.