The Senegal Migrant Quilt

Background

Watch our video about the perils facing Senegalese migrants at sea, made from video footage shot by the migrants themselves

This page tells a story of death and perseverance. It describes the journey made by migrants who leave West Africa in the hope of reaching Europe via the Spanish Canary Islands. Over 20,000 migrants made the trip in 2020, but many more turned back and over 2,000 may have drowned. The rate of departures is sharply higher in 2021.

This page tells a story of death and perseverance. It describes the journey made by migrants who leave West Africa in the hope of reaching Europe via the Spanish Canary Islands. Over 20,000 migrants made the trip in 2020, but many more turned back and over 2,000 may have drowned. The rate of departures is sharply higher in 2021.

The profiles and stories shown here are part of an initiative by The Advocacy Project to change the narrative of “illegal migration” and hear directly from migrants and their families.

In the summer of 2021 we asked Jeremiah Gatlin, one of our 2021 Peace Fellows, to travel to Dakar and investigate the causes of the migration and the human cost it involves. Jeremiah is a Masters student at the Fletcher School, Tufts University and he is an expert on the issue of migration. Before joining AP he volunteered in West Africa for the Peace Corps.

Jeremiah has produced extraordinary stories and remarkable material. He spent the summer working with returned migrants, family members and civil society leaders in the fishing village of Sendou-Bargny and the community of Thiaroye, outside Dakar. Both have sent migrants abroad, and struggled with the consequences.

Jeremiah interviewed five migrants who had recorded video clips from their voyage and agreed to share their footage with AP. Jeremiah worked with Gio Liguori, our video editor to produce a powerful video, Barcelona or Death (“Barca Wala Barsakh”) that can be viewed on YouTube.

The film also draws on a rap song about the journey that was subsequently recorded by one of the five migrants, Ama Ndiaye Thiombane (AKA Papa Mbissa Boy). It describes Mr Thiombane’s horror where migrants died on the boat and were thrown overboard: “Monsters show their face and start to eat people.”

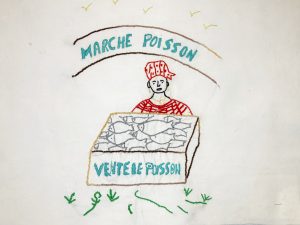

A s part of the project, several women from the village of Thiaroye have used embroidery to describe how their sons and brothers drowned and how their own lives have been shaped by tragedy. The stories are shown on the next tab and they are both poignant and deeply personal. One artist, Khady Mbengue describes how one of her brothers, Ibrahima died during the passage and was thrown overboard.

s part of the project, several women from the village of Thiaroye have used embroidery to describe how their sons and brothers drowned and how their own lives have been shaped by tragedy. The stories are shown on the next tab and they are both poignant and deeply personal. One artist, Khady Mbengue describes how one of her brothers, Ibrahima died during the passage and was thrown overboard.

Ms Mbengue’s second brother, Abdou Karim, survived but “came back a different person,” as she explained to Mr Gatlin. There are few services for returned migrants and clandestine migration is generally a taboo subject in Senegal. Many returnees suffer from mental illness.

The embroidery training was funded by AP and managed by OPEN-SARL, a social enterprise in Thiaroye that has provided support to over 750 returned migrants. The blocks are being turned into an advocacy quilt by Kathy Springer and a team of quilters in Indiana. Kathy has assembled other quilts for AP.

Jeremiah provides context for the embroidery and video in a series of blogs which place the blame squarely on misguided development policies in Senegal and pressure from the European Union, which is desperate to prevent the exodus of migrants from West Africa. For more information read this news bulletin. Email Jgatlin@advocacynet.org for more information.

Artists and Blocks