Ruh-roh, it’s been a long time since my last blog. And I thought I was doing so well keeping up with them! There has been a lot going on here in Athens, and my natural proclivity for avoidance has snuck into my blogigations (blog+obligations=blogigations… or blobligations? You decide).

Unfortunately, thinking back on the last week and a half to catch people up isn’t an exercise in rosy nostalgia. To be sure, some truly wonderful things have happened (including a recent mini-vacation to the island of Milos.) Earlier in the summer, one of my articles I had posted on the Fletcher Women’s Network Facebook group attracted the attention of a 2009 Fletcher alum named Hila Hanif, and through a whirlwind of serendipitous happenings, she arrived in mid-July to live with me and volunteer at the Greek Forum of Refugees and other organizations. More on her later (she may be peer-pressured into being my Friday feature podcast this week- my past two interviewees have ditched me so I’m lucky to have someone so great under my own roof!) Also, the GFR finally published the short film that had been in the making for months as part of their #RefugeesVoice campaign, with support from the Open Society Foundation. Featuring discussions from refugees and community leaders about integration in Greek society, the film is called “Integration Now: Participation is Everything.” Have a look- it’s a truly unique perspective that adds to the typical media narrative shown in the US. Beyond the protracted humanitarian emergency of refugees arriving and being stuck in Greece, how often do we hear about integration? Let’s face it—most of the refugees in Greece will be here for a long time, and this is an important conversation that needs to be had (even the EU agrees), and it is imperative to include refugees themselves in the dialogue.

But overall, the desperate situation of refugees in Greece has led to increasing tensions and outbreaks of violence. During the first week of July, locals on the island of Leros clashed with refugees and targeted aid workers—a number of NGOs decided to pull out due to safety concerns. Just a few days later, on July 14, there was a deadly stabbing in Elliniko Camp (the site of the former Olympic stadium), and two of the GFR Community Workers were beaten at the scene, prompting a press release on the issue from the GFR. The same week, I learned about the rape of a four-year-old girl at the unofficial Piraeus Port camp (which is in the process of being evacuated by authorities), and the following week we were confronted with a terrible story of a teenage Afghan boy arrested and physically and sexually abused by Greek police. I am tired of writing press releases with bad news.

And then there’s the hospital. I may have mentioned in previous posts that one of the services the GFR provides, voluntarily and out of necessity, is interpreting for refugees in Greek hospitals. There is no legal obligation of medical facilities to provide translators for non-native patients, and none of the hospitals in Athens have any programs or protocol to provide language services. Recently I wrote an article that we published as a call to UNHCR and the Greek ministry to address this serious issue, and Yonous (the GFR president) wrote a heartbreaking opinion piece after visiting the local children’s hospital on Eid (which I strongly suggest you read before continuing with this blog post). So when Yonous invited Hila and I last week to visit the children’s hospital with him, I didn’t think I could do it—I told Hila that I didn’t want to go because I figured I would just cry in front of the kids and that wouldn’t be helpful for anyone. But she was confident in me: “you’ll be fine, you’re strong,” she said.

So I went last Wednesday to the Agia Sofia Children’s Hospital with Hila, Yonous, and his wife and three-year-old daughter. When we got to the room, I saw the children that I had read about in Yonous’ article. There was Zabi, the 14-year-old Afghan boy who made the trip across the mountains from Iran to Turkey with a severe respiratory infection without his parents, and is now separated from his aunt who is in a camp while he remains in the hospital to receive treatment. He probably weighs no more than 60 pounds. And there was Yalda, the three-year-old whose father is in jail for being caught trying to cross the border illegally and whose mother is nowhere to be found. She isn’t sick, but there is no room in orphanages in Athens, so she remains in the hospital by herself. Next to her were two more Iranian siblings, a toddler and a baby, in the exact same situation. Their father is in Austria and their mother was caught trying to cross the closed border into Macedonia to make her way to join him, so she is being detained while the children are left in the hospital. Finally, there was Zainab. She is two-and-a-half, and she is in the hospital even though she isn’t sick either. She is lucky, however, because her father is with her. Her family was flown from a camp on Lesvos to Athens because her mother needed urgent surgery. However, her mother was in a different hospital, and there was a court order for Zainab to stay in the children’s hospital, because technically anyone who has arrived on any of the Greek islands after March 20 (the date of the implementation of the EU-Turkey Deal) must remain on the islands while their asylum claims are processed—so this is a way to maintain the family’s technical detention.

Although Zabi is nearly completely bedridden, the rest of the refugee children are healthy kids who are stuck inside most of the day. The hospital room has a balcony where people are allowed to smoke, and the doors are kept open almost all day. I shouldn’t have been surprised. “This is Greece,” Yonous often tells me when the shock at some terrible condition or story or law registers on my face. But seriously, smoking virtually inside a hospital, especially where there is a boy who has a respiratory infection?

While Hila sat with Zabi and spoke to him in Farsi, I learned from Yonous about Zainab’s father’s desperate situation. He had to go to the hospital where his wife was to have surgery the next day, but he wasn’t allowed to leave Zainab alone. When he visited his wife the day before, he had apparently left his daughter with a smuggler he knew for 5 euros, and was threatened when he returned by the hospital staff that the next time he took Zainab out of the hospital he would be arrested. I said of course I would come back and watch Zainab for the day while he visited his wife. I was getting increasingly emotional by my surroundings. The children were mostly happy and playing with women in white coats who I assumed were nurses, but I suddenly saw Hila step onto the balcony with tears streaming down her face, and that broke me. Later, I asked what made her cry. She had asked Zabi what he does for fun, what makes him happy, and he said, “not much, I mostly lay here and cry.”

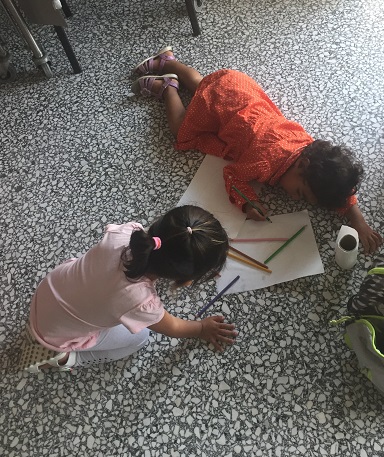

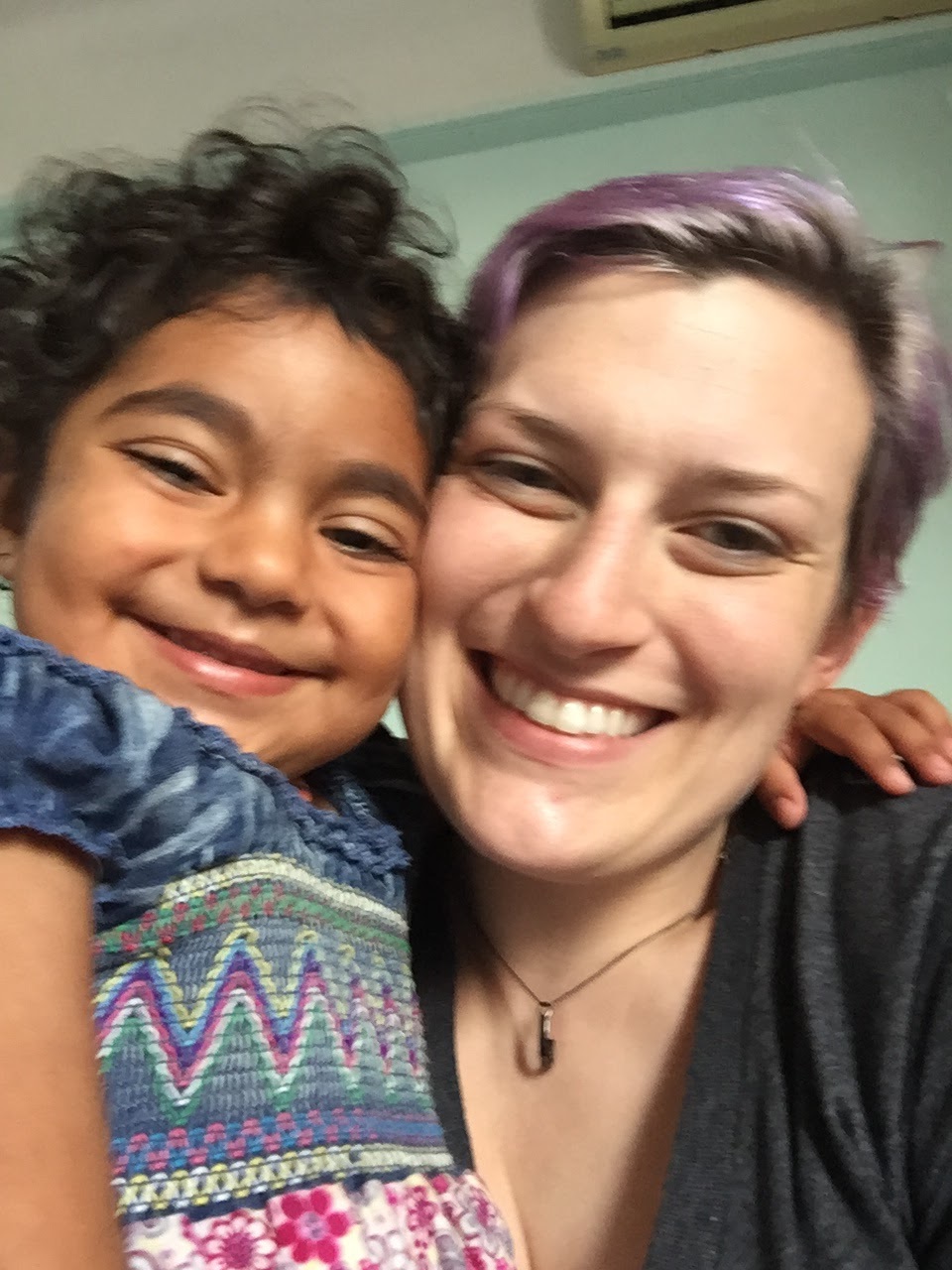

The next day, I went back to the hospital bright and early, loaded with toys and snacks and an intentionally cheery attitude. I had already bonded with Zainab, and she jumped into my arms when she saw me. I set to work spreading hugs and kisses and changing diapers, until soon two more women, wearing the same white coats as the ladies before, came in the room and seemed to take charge of Yalda and the Iranian brother and sister. I asked if they were doctors, only to learn that no, they were volunteers specifically assigned to the unaccompanied refugee children. They bustled about, feeding and cleaning and changing the sheets, and happily talking to or jokingly scolding the kids in Greek—and they were responding. In Greek! These little refugee babies who had been stuck here for so long had learned to speak Greek. I was amazed. And they clearly loved their white-coated ladies. I learned that they are part of an organization connected to the Greek Orthodox Church, and they come in three hour shifts, all day every day, and take care of the children. I almost cried with gratitude and happiness, especially when one of them told me, “yes, we’re all one big family.” They really were the family of these de facto orphans, and suddenly I didn’t feel that the situation was so terrible or desperate.

We spent the day playing outside, blowing bubbles, and eating popsicles when Hila came back to visit, bringing the welcomed snacks and a tablet for Zabi to play with. It was an exhausting but fun day, and we stayed late into the night once word spread that Hila could interpret, and doctors and nurses came out of the woodwork to pull her into different rooms to help with Afghan refugee families.

I actually had a hard time saying goodbye to Zainab when her father came back, and I thought about her and the other kids all weekend while I was on my little island vacation in Milos with Hila and her friends. There was an especially terrible moment when Yonous called to tell me he was informed of a child’s death at the hospital on Saturday, and the fifteen minutes between his first call and the next that confirmed it wasn’t Zainab or any of the others were some of the longest of my life. And what a terrible feeling, relief that the two-year-old refugee child that died wasn’t the one you know and love (it was another little boy who had been transferred from the island of Chios). If you read Yonous’ article that I linked, the picture he painted of little Yalda crying for her father is different from the girl I met, who was speaking Greek and clearly bonded with the women coming in and out to care for and play with her. While I am in awe of the dedication and love from the white-coated ladies, and especially the resilience and adaptability of refugee children, it is still sad to know that Yalda and the others are not with their own families in a healthy and whole home, learning their own language and culture.

UPDATE: I started this (terribly long) blog post this afternoon, then went back to the hospital with Hila. I just got back into the city, and am finally feeling a bit rosier about things. The two Iranian babies are gone—their mother was released from a month long detention, and she picked them up. Yalda was as sassy as ever with another white-coated lady, but when Hila spoke to her in Farsi, she responded in Greek. Zabi was more relaxed and talkative than I’ve seen him since we met—he had a visit from a social worker recently, who told him about his relatively bright asylum options because of his medical status. (He also commented to Hila that I was really sweaty, so at least he’s as snarky as a teenage boy is supposed to be). Zainab was almost as happy to see me as I was to see her, but unfortunately she now has a cough—I guess that’s what happens when a healthy kid has to stay in a hospital. I was concerned that her father wasn’t there, but he returned in the middle of our visit, happy to report on his wife’s progress recovering. I don’t know what will happen once his wife is discharged from the hospital, but we are going to put him in touch with a lawyer from one of our partner organizations, the Greek Council for Refugees, in hopes that the family won’t have to go back to Lesvos.

There’s so much more to say about these kids, but I am quite sure if there’s a word limit, I’ve hit it. I was a little worried about bonding too closely with Zainab—what if she starts to expect to see me, and then I leave and disappoint her? But in reality, I’m the one who is having separation anxiety. It is going to be really, really hard to leave Athens in a couple of weeks.

Posted By Mattea Cumoletti

Posted Jul 27th, 2016

6 Comments

steven cumoletti

July 27, 2016

I’m so glad you are sharing these insightful stories.

steven cumoletti

July 27, 2016

Opps. Just remembered that’s your role there, but yiu do it very well.