This is a real story, not a fairytale. This is a story about humanity.

Every story consists of different parts. Like fitting scraps into puzzle, each part of the story counts as scrap that needs to be arranged to shape a clearer picture. But wait, in this story, the more part I knew, the more scrap I found, the more complex it became. No wonder, because it’s a reality, not a fairytale. Fairytale will come to happy ending, but human story? Who knows?

This is the story about the struggle for dignity.

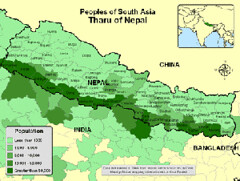

Approximately, 600 years ago, a large group of people came into the Tarai area in Nepal. Tarai was characterized as wild lowland which swampy and marshy, with forest of Sal trees, not to mention its virulent strain of malaria. These people opened the jungle, built houses on elevated wooden platforms to protect themselves from dangerous animals, cultivated lands, traded timbers, lived their life in Tarai. Others have tried to settle there but failed, mainly, because of malaria. Famous of the immunity to malaria, they remained to be the only permanent inhabitant of Tarai. They are the Tharu.

In 1950s, Nepal Government by the support of International Development Agencies conducted malaria eradication project in the Tarai. This project marked a completely different era for the Tharus. Many people from the hills migrate to the fertile lowlands of Tarai. At the same time, land reforms was introduced as part of the post-1951 modernization sought to give the tenants of the state property rights in the land they cultivated. But this system of private property relations, whose implications many ordinary Tharu tenant farmers appear not to understood. It, then, led to the exploitation at hands of some immigrants and to the loss of land they had acquired. Throughout the Tarai, particularly in the west, Tharus have lost control of land either through outright fraud, manipulation or indebtedness. In the western Tarai, many of them have been reduced to the status of bonded labor (the so-called kamaiya system).

In the Kamaiya system, every part of the Tharu family has his/her own role. Father and son responsible for farming and agriculture, while mother and daughter work as domestic worker. Girl who work as domestic assistance is also known as kamalari. Kamaiya system forced Tharus to work as bonded laborers to pay their debt to the landowners. If a man unable to pay off the debt, it’s automatically transferred to his son. This debt bondage was also reinforced by Nepal’s legal code. In all cases the landlord was free to pay his bonded laborers as much as he wants. Generally, landlords kept the wages as low as possible, forcing bonded laborers to keep borrowing money from them. Thus, most of bonded laborers keep falling deeper into debt. Besides, bonded laborers could possibly be transferred to another landlord simply by paying off their debts to the former landowner. Every year, thousand of Tharus were bought and sold in this way in the Dang-Deukhuri, Bardiya, Kailali, Banke and Kanchanpur Districts of western Tarai of Nepal. Even though, data from the Government of Nepal showed a smaller number, most of the studies agree that in 1995 total number of bonded laborers in the western Tarai was estimated to be around 100,000—most likely the difference occurred because the government data didn’t take account women, children, and older kamaiyas. Thus, this system was equivalent to a form of slavery that is designed to maintain a source of cheap labor for landlords.

Brought up in unjust situation, Tharu youths didn’t keep silent. A seventeen-year-old Tharu named Dilli Bahadhur Chaudary, established a development organization for their community. This organization began with 34 members, most young Tharu men from Dumrigaon and neighboring villages. Within a month of its inception the Dumrigaon Organization established a literacy class for uneducated local Tharu villagers, organization members also made plans to implement an income generating program, and launch a political campaign against oppression. Suspected as rebel, the government of Nepal threw Dilli into jail twice under the Public Security Act, and forced him to stop his organization. But, Dilli never stop. This organization, then, well known as BASE (Backward Society Education).

Together with various organizations, local and international, BASE actively campaigned for justice for bonded laborers. Then, in July 2000, kamaiya system was abolished by the Government of Nepal, followed by the enforcement of prohibition for kamaiya Labor Act in 2002. The government of Nepal also implemented Landless People Resettlement Program and other similar programs for the recovery of ex-kamaiyas.

Today. The struggle is far from end.

Many kamaiyas were liberated from their former landlords and released into poverty without any support. Others received land that was unproductive. Many ex-kamaiya families still live in chronic poverty; a lot of them settle in very remote area without access to water, electricity, and other basic needs; girls (the kamalari) are sent to the city to have a better life, but end up working day and night without education and easily exposed to abuse. Poverty, illiteracy, marginalization, and discrimination form a vicious circle that trap the ex-kamaiyas, it makes very difficult for them to escape.

There are a lot left to do.

(From various sources: Guneratne, 2002; Cox,1994 ; ILO Reports, World Organization Against Torture Report, 2005; etc)

_________________

We are developing BASE Facebook fan page. Join us to support BASE and marginalized community here to continue their struggle for dignity.

Posted By Maelanny Purwaningrum

Posted May 25th, 2011

4 Comments

Nguyen Mai

May 25, 2011

Melany, I love the way you are unfolding stories and connecting them. Up to now, this is my most favorite post. Keep up! 😉

Karie

May 28, 2011

This is such a powerful story! The irony of “development” actually hurting the Tharu was one of the things that struck me the most during my time in Nepal last summer. The best intentions can go horribly wrong if you don’t think about consequences all the way through to the end. It makes me worry a lot about what possible consequences development workers forget about today.

Great job with the blog post, and keep up the good work!